The Culture Cash-in On Raves And Festivals

Seamus O’Conner takes a look at the so-called “new age entrepreneurs”, using the CJA and the cultures it sought to crush as a source of profit.

Squall 10, Summer 1995, pp. 36-38.

Mean Fiddlers And Market Manipulators

"This afternoon 25,000 people will congregate on 60 acres of Oxfordshire park land in the first of a new generation of ‘raves’ since the Criminal Justice Act became law," wrote Alex Bellos in the Guardian (6/5/95).

The article - a fair-sized one with a photograph - must have had the Mean Fiddler Organisation, part organisers of the event, rubbing their palms together in prospective financial glee. What better publicity for a rave party than to be associated with the new politicised sound systems and dancers.

It’s the kind of PR engineering that Vince Power and his Mean Fiddler Organisation have employed and basked in ever since they did the nigh impossible and made a success of the original Mean Fiddler music venue in out of the way Harlesdon, North London. Relying on the local Irish contingent to attend a rota of known Irish acts, Power hasn’t looked back since.

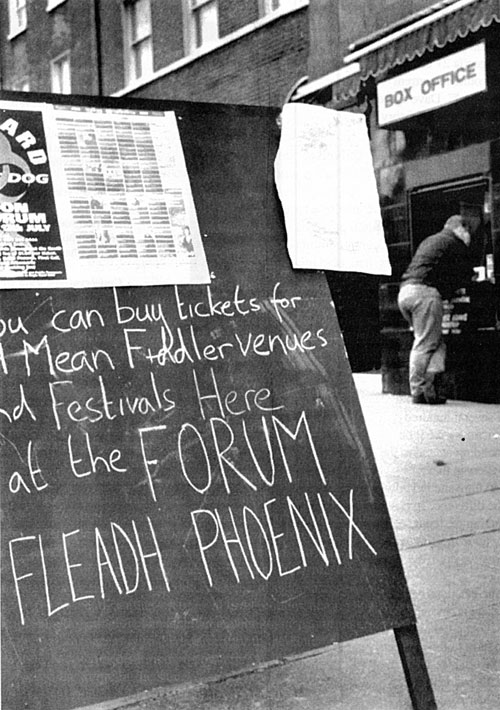

The Mean Fiddler Organisation now owns seven of the major venues in London, as well as running the Phoenix Festival near Stratford, the Reading Festival, several large one day events (Fleadh, Madstock etc) and now, in conjunction with Universe, the Tribal Gathering.

As regards bringing Irish bands to London, the Mean Fiddler has played an important part, but the meteoric rise of the Organisation has to some extent been ensured by cultural exploitation.

Commercially unknown bands playing at the original Mean Fiddler venue were often treated with a disrespect manifesting itself in bizarre ways. Firstly, Vince Power’s outlets operated extortionate ticket deals for unknown bands playing in his venues.

Secondly, even headlining bands were refused permission to bring water into the venue by the Mean Fiddler staff. Singers were expected to buy water from the bar in order to keep their vocal cords lubricated, an early preliminary to the ‘taps off - expensive water’ scenario that has come to characterise commercial rave venues.

When the Mean Fiddler Organisation bought out the Jazz Cafe in Camden, London, one of their first moves was to get rid of the ticket price concession for the unemployed.

Then in 1993, after already having manoeuvred their way into the position of promoters of the Reading Festival, Vince Power and the Mean Fiddler Organisation saw the commercial potential spinning off from increasing public interest in Glastonbury Festival, and launched the Phoenix Festival near Stratford. The market-directed plan seemed obvious. Choose a name which had ‘new age’ connotations, enclose an area with five stages, each with different themes a la Glastonbury, charge £50 (£58 this year) to get in and maximise profits by barring all people from bringing in drinks of any kind onto the site.

In that first year Vince Power pushed things too far for many of the kind of festival-goers who had come looking for the open cultural experiences developed through free festivals and still to be found in pockets at Glastonbury. At midnight on the first few days of the first Phoenix Festival teams of officials toured the campsite situated outside the walled-off stage area, turning off boogie boxes and errant sound systems and dousing fires with hose pipes.

People felt conned and hemmed in by the anti-festival spirit and commercial capitalisation and a riot ensued. The walls of the stage area were attacked and for a moment it looked as if the whole site was about to go berserk. Hastily, sound systems were asked to start up again in the campsite itself, diffusing the anger and averting further rioting.

This year the Mean Fiddler Organisation is to give some of the proceeds of Phoenix Festival to Amnesty International just as Glastonbury contributes to Greenpeace. The Mean Fiddler Organisation have put Amnesty’s name prominently on their Phoenix Festival posters and, although Amnesty International needs as much money as it can get, the Mean Fiddler’s decision is more likely a commercially astute move, based on Glastonbury’s example, rather than any surge of corporate altruism. After all, the ticket prices for the two events are now almost identical, although the Phoenix Festival offers considerably less in terms of variety.

It is easy to see the same market planning involved in the so-called “new generation of rave” described and hyped up by the Guardian. The name ‘Tribal Gathering’ suggests another calculated piece of commercial nomenclature, designed to tap into a newly identified sense of sound system tribalism. The huge posters advertising the event outside the Mean Fiddler’s ‘Forum’ venue in Kentish Town, North London, provided an obvious visual contrast situated as it is right next door to the church squatted by the Rainbow Tribe. As the Rainbow Environmental Centre struggles with its £2,000 electricity bill, there would not be one person living at the old church who would had have had the £25 required just to enter the so called ‘Tribal Gathering’.

Far from being a “new generation of raves” the Tribal Gathering was in fact the same old story. In Issue 8 of SQUALL we ran an article entitled ‘Who spiked the Dance Floor’ pointing out that legal restrictions on the right to party has pushed dance culture into the hands of the commercially-motivated, culturally exploiting the need to dance.

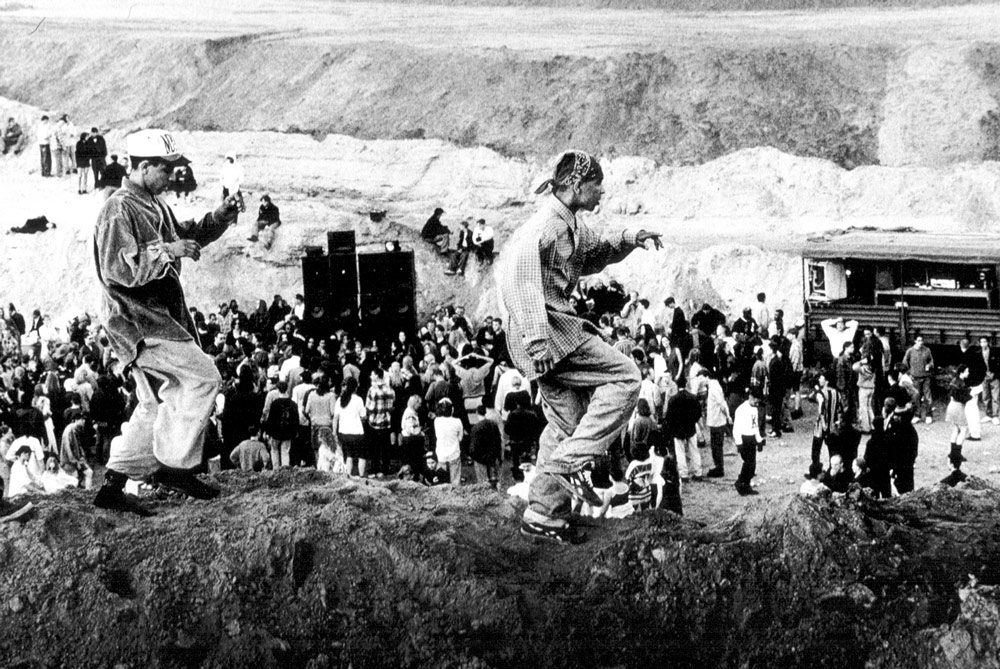

The Criminal Justice and Public Order Act is a specific hammer-blow to free party groups organising dances genuinely open to members of the community, regardless of whether they have the £25 asking price for entry. If Alex Bellos had genuinely wanted to discover a ‘new generation of raves’, existing despite the presence of the Criminal Justice Act, he would have done far better to have visited one of the new series of Exodus Collective raves, making community use of disused quarries and warehouses and charging just the one pound entry required to keep the ball rolling. He would have also done better to have paid a visit to one of the Bristol warehouses where the Sunnyside Collective organise large scale parties that are free to enter. Or Desert Storm in Scotland, FreeBase in Wales, Lazy House and Ebb in the West Country, or a host of other free party pushers.

“Tribal gathering?,” says Diplo, from the Sunnyside Collective. “Yeah I went to one - it was the Beltane Festival near Exeter. The only way we’d have been at that Oxfordshire do would be to have shown up and done a free party in the Car Park for those that didn’t have the £25 to get in.”

The Guardian chose to follow up its coverage of the so-called ‘Tribal Gathering’ with a large article in its Arts section (8/5/95) subtitled: “The Criminal Justice Act put the rave under House arrest. But it’s out and it’s phat in Oxfordshire.”

It talked of how the “repetitive beats” mentioned in the Criminal Justice Act were the very ones rebelliously played in Oxfordshire that weekend. However, the Criminal Justice Act helps rather than hinders such commercial raves. For a start it limits the competition - making it harder for people to organise their own. Secondly, it allows profit-mongers the opportunity to exploit the public’s desire to dance; with large amounts of capital ensuring an official licence, and large entrance fees ensuring huge profits. It is in effect a cultural corruption, and all the sadder for the fact that most of us go along with this subtle but effective steering.

It just so happens that the Exodus Collective were running a rave in a disused quarry on the same night as the Tribal Gathering.

“The difference was quite amazing,” says Mary Anna Wright, a sociology researcher who attended both events. “The Exodus party won hands down; I found the other one so contrived. Also the fact that one event was legal and it was boiling hot with people sweating buckets, and the other was illegal and much safer.”

Nicholas Saunders, author of ‘E for Ecstasy’ - an authoritative academic book on drug culture, also danced at both raves:

“It was the sort of event where people feel very bounded together and when there’s a big public event with lots of stewards around such as the Tribal Gathering, they don’t feel so personally involved with looking after each other; it’s a bit municipal in a way. The Tribal Gathering was very efficient and well-organised but the Exodus rave had the atmosphere.”

Mary Anna Wright was none too impressed by the Guardian article that preceded the event: “Fucking hell - I was so angry because Alex Bellos phoned me up and I gave him most of the information for the article. I put the whole argument about the lack of safety at events because of the effects of the Criminal Justice Act and all these clubs that are mixed up with all this tap turning off business but he ignored it completely.”

Nicholas Saunders agrees that Bellos’s angles were wide of the mark: “The Tribal Gathering was the kind of event we are left with because we have such heavy clamp downs like the Criminal Justice Act.”

However, the author of the Guardian ‘Arts’ review on the Tribal Gathering, Andrew Smith, concluded that: “You could stage one of these things almost anywhere and, if you got the music right and allowed people to bring their own drugs, they’ll swallow it. This makes them easy to please. It also makes them easy to exploit. The Tribal Gathering came down on the right side of this equation.” A sorry and safe conclusion in many respects.

The Sunnyside Collective from Bristol sent a letter to The Guardian which, to the newspaper’s credit, they printed with the headline: “Rave on to the sound of money changing hands”(15/5/95).

In the letter, Sunnyside pointed out that the cost of entry “priced out those really criminalised by the CJA - the unemployed, the young, the poor. To claim that such events unify ‘dance culture in defiance of the Act’ is plainly disingenuous.”

A member of Universe, co-promoters of the Tribal Gathering with the Mean Fiddle Organisation, approached the Exodus Collective to ask if they wanted to do a pitch at the event. It would have surely been a commercial coup if the organisers had managed to get Exodus to attend but, after discussing the proposal at a meeting, the Collective elected not to take up the offer due to the prohibitive ticket price. Since their decision was made the proposed ticket price actually went up.

“They were trying to make out that the Tribal Gathering was the sort of thing the Government are trying to stamp out but that’s the thing they’re trying to encourage - the mass dollars bit,” commented Exodus’s spokesperson Glenn Jenkins.

Entrance prices were also the issue at the Safer Dancing Conference that took place in Manchester in March. Organised by a group called Lifeline, in conjunction with Manchester City Council and the Home Office, the conference was designed as a discussion of the issues raised by a spate of deaths in commercial rave clubs. Representatives of many the big clubs in Britain were in attendance, including those that still switch off cold water taps in their toilets to maximise profits from water sales at the bar.

Glenn Jenkins from the Exodus Collective had been invited to come and speak at the Conference by Lifeline and so travelled all the way up from Luton with three of the Collective’s own drug welfare people, known as the Exodus Drugs Squad.

“When I got to the door they gave me a pink badge and said the other three lads can’t come in,” recalls Jenkins. “I told them that all they wanted to do was stand at the back but they told us the conference was full up to the brim. So I went inside to sort it and there was stacks of room. But they were saying ‘why should you lot be allowed in for nothing when all these others have to pay?”’

The answer, of course, was obvious. The commercial club owners attending the Conference could well-afford the staggeringly prohibitive £65 entrance fee. Exodus on the other hand charge next to nothing for their raves and make no profit. The people that work on the project do so for the love of the dance and receive no payment. Once again the Exodus Collective contingent were told the conference was “filled to the brim”.

Someone already in the conference hall, and a friend of the Exodus members, offered to pay their entrance fee and the organisers accepted.

“That made it stink even more,” recalls Jenkins. “It gives away their true game - they had that hall for free off Manchester Council and still they were charging £65 to get in. I was invited to speak - but were told there’s more no more room unless you’ve got £195. I refused to go in and chucked my passes back at them.”

The farce continued when it was realised that many of the people in attendance at the conference were from clubs who turn their water taps off. One delegate did in fact stand up at the conference and accuse Club UK (Wandsworth, South London), amongst others, of operating a no cold water tap policy. But conferences come and conferences go - and what do they mean?

“I went to Club UK in April and I couldn’t believe it,” a dancer called Mary told SQUALL. “It’s 1995 and the hot water in the women’s loo was so hot you couldn’t even wash you hands in it and there was no cold water. We had to get the men to go into their loo and get some cold water out.”

It is no small irony that a prominent member of Universe, who co-organised the Tribal Gathering with the Mean Fiddler Organisation, is also one of the promoters of Club UK.

Will the phoenix or the vulture rise from the ashes?

Megatripolis and Bad Dream Entertainment

Universe and the Mean Fiddler Organisation are not the only profiteers to come riding in on the backs of the new culture. Megatripolis in London’s West End Heaven Club has proved itself to be another example, exploiting the newly-identified market of the festival/anti-criminal justice act posse.

From the word off, Megatripolis at Heaven was always an uneasy combination. Heavy security on the door sat uneasily with the clown they employed to give you a sweetie as you went in. The £2.80 for a bottle of beer sat incongruously with the free festival vibe that the club was putting across.

“It’s something that did start off so positively but people were lied to basically; effort, talent, contacts were taken from people and it was all one way,” recalls Alistair, one of the core organisers of the club night. “There was deception involved in the things that were going on but there was so much work to do that we never really looked at it.”

“The people who ran Megatripolis were not the people who owned Megatripolis - that is a crucial point,” adds Gary, who joined the team a year after they opened at Heaven.

“There was lot of people involved in the organisation who I know were genuine people and they were taken for a ride really by the owners.”

The problem came not from Heaven’s management but from the owners of the Megatripolis night, a so-called partnership of two individuals from a company called Dream Entertainments and hippy-zippy entrepreneur Fraser Clark.

“Fraser had the idea for the club and didn’t know how to do it,” says Gary. “So he pulled in a lot of underground type people in order to reflect that kind of thing in the club. Then he brought in Dream Entertainments to act as the business background, and they very carefully and cleverly trademarked everything in their name.”

Dream Entertainments was the company name of two individuals, Peter Mosse (known as Bugsy) and JJ Abdul Nasier (known simply as JJ). JJ was also an associate partner (financial services salesman) for Rothschild bank. Megatripolis itself is a registered company but was under the entire ownership of Dream Entertainments, despite the fact that the club had been built up on the backs of a large number of free party spirited people.

Indeed, there were many people involved in the running of the club who thought that despite the economic intentions of the business-heads behind the Megatripolis night, something festival-like could be made of the night; providing an important example of such spirit in the middle of the city.

Right from the beginning, Megatripolis was a commercial success. Correctly predicting the new market potential of the festival/rave scene, the club was almost invariably full, netting between £6,000 - £8,000 a night. In theory this should have meant that sufficient money was available to re-invest in the club and to pay the people who were doing all the work, but in reality this never happened.

“Those creative people that put the work in right at the start never got the financial reward, acknowledgement or respect they deserved,” says Blue, another core organiser.

“I was always told there was not much money there,” adds Gary. “So because of this I used to book DJs and say 'look I’m really sorry mate, I know Ministry pay you £500 but we can only pay you £100’. I had to do a lot of that with DJs, bands, speakers, people who do the decor - everything.”

Meanwhile, Fraser Clark was busy hyping up the club as the “meeting place for the new consciousness” at the same time as short-changing the expenses promised to speakers he had hired in to lend the club a culture-political credibility. At one stage, Clark was paid by a group who wanted to use the Megatripolis name to run a night at the Astoria; another venue. No other members of the hard-working Megatripolis organisers saw any of the money.

Blue had been one of the main Megatripolis organisers ever since the club night opened in Heaven. With some previous experience in management and marketing consultancies, he was brought into to help organise the budgeting of the club, as well as for his connections on the underground free-party scene.

“I checked into Fraser’s background and knew he was financially irresponsible; his integrity around money was appalling - he wasn’t malicious, he just didn’t give a bollocks. I was brought in to keep an eye on this. I would say now that he was a backrider.”

It now seems likely that backriding was a common occurrence at Megatripolis, with Fraser Clark as only a minor shark in the set up. Dream Entertainments took a profit share of the takings and had the responsibility for paying the tax on the night, withdrawing a sizeable fraction of the takings each week for such purposes. Blue finally sussed on to the fact that Megatripolis was not registered with the tax office and that something was going wrong with the handling and distribution of the profits.

“The amount of money in the company account was many thousands short of what it should have been on the basis of turnover and expenditure - it just didn’t match,” says Blue.

One of Fraser Clark’s multitude of philosophically manipulative soundbites was that Megatripolis was a “corporate structure with a co-operative philosophy”.

Blue has little time for the realities of such sloganeering: “I’ve got no problem with people who run a project as a company structure but you can’t use a co-operative philosophy on top of a corporate structure as a device to make personal profit - it sucks.”

One of the reasons why the creative team behind the Megatripolis night continued to work for so long in such exploitation was firstly that no-one was aware of what was happening behind the scenes, and secondly because the creative organisation of the club on was a full time and exhaustive job with little pause for thought.

“We just didn’t want to believe that anybody was taking the whole thing for a ride,” adds Blue. “But then it was the realisation that things were not going to change - that they weren’t simply unaware of what the underground movement was really all about or what the whole thing was being done for - they simply weren’t interested.”

Fraser Clark was finally ousted from the Megatripolis partnership by the Dream Entertainments duo, and left for America. The creative Megatripolis posse reserve little hatred for Clark, simply saying he was a “megalomaniac” and “difficult to work with”.

“We split with him out of embarrassment rather than any hate or malice,” says Blue.

Dream Entertainments went bankrupt this year, after a huge unpaid tax bill arrived through their door. Bankruptcy of course foregoes tax obligations. By this stage however, most of the original team had now left, convinced that the commercial back-riders were throttling the very free-festival vibe they had worked so hard to foster.

One legacy of the venture is that a lot of very positively spirited people left the project feeling extremely angry at the use of new-consciousness philosophies and sound bites, designed solely to manipulate creative individuals into working hard for next to nothing, whilst others were raking it in.

“A lot of people have come out of the project cynical and in pain. It was a big thing to do - a massive project every week and a lot of people gave all their time. When we found out what was going on it was appalling; such a disappointment,” winces Blue.

“The whole thing is still swinging around in my head,” adds Alistair. “I just feel a lot less trusting and I don’t like that feeling.”

The greatest danger resulting from the use of new-consciousness sound bites to back ride positively spirited people is, of course, that the fatter the riders become, the greater the chance they will break the backs of those they are riding upon. In nature it is called ‘destructive parasitism’. A disturbing, but not unusual, trend of spouting the philosophy to collect the cash, has given rise to the warnings of ‘beware the new-age entrepreneur’. However, despite the tremendous disappointments experienced by all those who fought for the festival spirit at Megatripolis, the creative team seemed to have survived the negative onslaught of the bad experience.

“We learnt an enormous amount by doing it and we also learnt an enormous amount about what can go wrong and how it can be prevented, as well as what we can do to clean ourselves up," says Blue.

Alistair, Blue, Gary and others involved in putting the Megatripolis night together have now formed a new posse called AngelTech, and are organising some free-parties in Brighton before heading off to Spain to dance in the sun for a while.

“We still love it - watching people having a party watching people come to a thing and go away changed and enlivened. Their vital signs go up - their energy is better - they think better of things. It makes a difference and it’s worth doing,” affirms Blue.

Other members of the team, involved in loading the equipment and decor at Megatripolis, also left in disgust and have since started up Exclamation on Thursday nights at the Fridge in Brixton, South London. Costing £4 to enter, their debut night attracted a packed house for what was described as a “cracking night”.

Phoenix, Megatripolis, Tribal Gathering - the meeting place for the new consciousness or the market place for the same old unconsciousness? Informed discernment is the key to healthy choice.

“It’s made me look twice and more carefully about how much I involve myself and with who. I try to keep my judgements under control but I do use more discernment,” says Blue, with lessons learned and back not broken.

Related Articles

Recreational Drug Wars - the battle waged between vested business interests and rave culture - Squall 12, Spring 1996

Tribal Gathering - Fooling The Dancers - rave culture co-opted by Mean Fiddler and other commercial forces - Squall 13, Summer 1996

There's No Such Thing As A Free Festival - Sam Beale talks to some modern day festival organisers about how to sow the festie-vibe in the harsh nineties - Squall 14, Autumn 1996

Assemblies Of Celebration, Assemblies Of Dissent - an overview of recent decades of festivals, raves, travellers and protesters - 1998