Assemblies Of Celebration, Assemblies Of Dissent

Jim Carey reviews the recent political history of Travellers, city kids, raves and festivals and reveals the multi-tactic approach used in attempts to annihilate an emerging culture of celebration and dissent.

1998 published in SchQUALL, 2000

When the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act began its passage through parliament in 1993, there were many who were genuinely flabbergast.

Why were travellers, squatters, ravers, political protesters and public assemblies considered such a threat to the nation that new criminal law was required? As Home Secretary in 1992, Kenneth Baker broadcast the government's opinion thus: "We will get tough on rapists, tough on armed robbers and tough on squatters". Such farcical juxtapositions became a feature of the passage of the new law and an indication of the extent to which the government were prepared to go in persuading the British public that such activities were harbouring nests of parasitic criminals. Such selective demonisation was nothing new of course, though few thought that it would manifest itself in such overtly draconian fashion. That a "series of repetitive beats" should become the defined target of criminal sanctions, reinforced the impression that the Nazi penchant for targeting cultural undesirables was now finding new expression in the UK. Far from an isolated incident however, the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act was merely one of the more overt measures in a long term strategy of annihilation.

The networking hub of the UK's so called 'underground' culture (an increasingly inappropriate nomenclature) were the unlicensed public festivals which had been proliferating across the British Isles since the early seventies. Primarily designed to provide financially accessible community celebrations, these gatherings also harboured active expressions of rising public dissension; populated as they were by an outflux of disaffected youth determined to create a life for themselves outside the market-myopic. The largest example of these gatherings took place annually at Stonehenge around the date of the summer solstice, the longest day. Having begun as a small gathering in 1974, the Stonehenge Solstice Free Festival attracted 30,000 people to it's last uninterrupted incarnation in 1984.

The political significance of this 'Mother' of a flourishing festival circuit was exacerbated by its location. Not only were 30,000 people gathering without the presence of the Police, they were doing so on one of the largest military training grounds in the UK and in the highly Conservative county of Wiltshire. To the British establishment this was a flagrant challenge, and one which, much to their annoyance, was getting larger every year.

Furthermore, with environmentalism as a prominent feature of festival culture, those attending the gatherings - including the swelling ranks of British travellers - began involving themselves in direct action, the main focus of which concentrated on nuclear energy and weaponry.

Between 1980-1984, convoys of travellers took part in public operations known as Cruisewatch. This involved the overt tailing of mobile Cruise missiles, transported from silos in Wiltshire to secret locations in neighbouring counties. This was a particularly sensitive area for the government. Secretly located nuclear missiles formed a major part of the UK's nuclear deterrent tactics, with mobility designed to confuse the Soviets in the event of an attack. Anti-nuclear campaigners argued such manoeuvres brought the possibility of nuclear war even closer and effectively blew the government's cover by following the missiles everywhere they went.

The term 'Peace Convoy' was a generic term coined by the media and, with the continual involvement of travellers in anti-nuclear demonstrations, it was a term that stuck.

In June 1982, a 'peace convoy' left Stonehenge to support the nuclear weapons protest outside Greenham Common in Berkshire; holding an impromptu festival on the perimeter and cutting the fence. In September the same year, another convoy incorporated the Sizewell B nuclear reactor in Suffolk into its itinerary of East Anglian festivals. Once again they established themselves in the car-park and stayed for a week. In 1984, the significance of these stand-offs was brought to a head when another peace convoy took part in a large demonstration outside the US Cruise Missile base at Molesworth in Cambridgeshire. Along with other contingents of anti-nuclear protesters, travellers occupied a perimeter site for five months; planting and reaping crops whilst a group of Quakers built a Stone Chapel of Peace. Following a High Court possession order granted in February 1985, the entire protest camp was finally evicted using soldiers from the Royal Engineers regiment. Significant to the political escalation resulting from these protests, the eviction was attended by the then Minister of Defence, Michael Heseltine, famously arriving on site in a camouflage flak jacket. Meanwhile the festival circuit harboured an increasing multitude of campaign groups - particularly those connected with the environment - assembling en masse, distributing information and discussing action. Up until 1985, these burgeoning assemblies of alternative living and dissent stood successfully defiant in the face of Margaret Thatcher's designs on an ultra-efficient market mono-culture. In 1985, however, the 'Peace Convoy' and its associated culture became the target of a multi-strategic campaign of annihilation, inaugurated with blood at Stonehenge.

The Battle Of The Beanfield

It is difficult to convey the extent and affect of the berserk circumstances that occurred on June 1st 1985, but their socio-political ramifications were immense. A convoy of travellers' vehicles left an impromptu park-up site in Savernake Forest to head towards Stonehenge. Seven miles from the Stones, and still some way out of the newly imposed four and half mile High Court exclusion order, police blocked the convoy with three lorry loads of gravel. After a short stand-off, the acting Deputy Chief Constable of Wiltshire, Lionel Grundy, gave orders for his men to begin attacking the vehicles and arresting drivers. When word swept through the convoy that police were smashing windscreens at the front and the back of the line of vehicles, travellers pulled their vehicles off the A303 and into an adjacent grass field. At this stage, many travellers were keen to return to the Savernake Forest site, but were told by Wiltshire Police that those wishing to leave the scene could only do so without their vehicles (homes).

After a tense wait, the pressure cooker finally exploded when over 1000 police, drawn from five constabularies, charged into the field wielding truncheons. In an effort to escape, the convoy drove from the grass field into the adjacent Beanfield looking for a way out. A huge number of riot police charged in behind them to commit a now legendary carnage, inappropriately referred to as the Battle of the Beanfield.

Public knowledge of the events of that day are still limited by the fact that only a small number of journalists were present in the Beanfield at the time. Most, including the BBC Television crew, had obeyed the police directive to stay behind police lines at the bottom of the hill "for their own safety".

One of the few journalists to ignore police advice and attend the scene was Nick Davies, Home Affairs correspondent for The Observer. He wrote: "All of us were shocked by what we saw: police tactics which seemed to break new bounds in the scale and intensity of its violence. We saw police throw hammers, stones and other missiles through the windscreens of advancing vehicles; a woman dragged away by her hair; young men beaten over the head with truncheons as they tried to surrender....the police operation became a chaotic whirl of violence...basic rules of police behaviour were abandoned. The identification numbers of most officers were concealed by flame-proof overalls....I saw a young man's glasses swiped from his face and front teeth break under the raining blows."

The only national television camera crew in the Beanfield was from ITN. Reporter Kim Sabido spoke to camera: "What we the ITN camera crew and myself as a reporter have seen in the last 30 minutes here in this field has been some of the most brutal police treatment of people that I've witnessed in my entire career as a journalist. The number of people who have been hit by policemen, who have been clubbed whilst holding babies in their arms in coaches around this field, is yet to be counted...There must surely be an enquiry."

However, when the item was nationally broadcast on ITN news later that day, Sabido's voice-over had been removed and replaced with a dispassionate narrator. The worst film footage was also edited out. When approached for the footage not shown on the news, ITN claimed it was missing.

"When I got back to ITN during the following week and I went to the library to look at all the rushes, most of what I'd thought we'd shot was no longer there," recalls Sabido. "From what I've seen of what ITN has provided since, it just disappeared, particularly some of the nastier shots." Some but not all of the missing footage has since re-surfaced on bootleg tapes and was incorporated into the 'Operation Solstice' documentary shown on Channel Four in 1991.

A similar story of missing visual evidence transpires when trying to track down the images taken by photojournalists. Ben Gibson, a freelance photographer working for The Observer that day, was arrested in the Beanfield after photographing riot police smashing their way into a traveller's coach. He was later acquitted of charges of obstruction although the intention behind his arrest had been served by removing him from the scene. Most of the negatives from the film he managed to shoot disappeared from The Observer's archives during an office move. Fellow photographer Tim Malyon narrowly avoided the same fate:

"Whilst attempting to take pictures of one group of officers beating people with their truncheons, a policeman shouted out to 'get him' and I was chased. I ran and was not arrested." Malyon thought his film was safe after storing it with London solicitors' firm Birnbergs. However, despite the fact that his photographic negatives were never supposed to have left Birnbergs' possession, they too disappeared. Fortunately, some of Ben Gibson's and Tim Malyon's prints have recently resurfaced. One unusual eye-witness to the Beanfield nightmare was the Earl of Cardigan, secretary of the Marlborough Conservative Association and manager of Savernake Forest (on behalf of his father the Marquis of Ailesbury). He had travelled along with the convoy on his motorbike accompanied by fellow Conservative Association member, John Moore. As the travellers had left from land managed by Cardigan, the pair thought "it would be interesting to follow the events personally". Wearing crash helmets to disguise their identity, they witnessed what Cardigan described as "unspeakable" police violence.

Cardigan subsequently provided eye-witness testimonies of police behaviour during prosecutions brought against Wiltshire Police, including descriptions of a heavily pregnant woman with "a silhouette like a zeppelin" being "clubbed with a truncheon" and riot police showering a woman and child with glass.

"I had just recently had a baby daughter myself," recalls Cardigan. "So when I saw babies showered with glass by riot police smashing windows, I suppose I thought of my own baby lying in her cradle 25 miles away in Marlborough." After the Beanfield, Wiltshire Police approached Lord Cardigan to gain his consent for an immediate eviction of the travellers remaining on his Savernake Forest site. "They said they wanted to go into the campsite 'suitably equipped' and 'finish unfinished business'. Make of that phrase what you will," says Cardigan. "I said to them that if it was my permission they were after, they did not have it. I did not want a repeat of the grotesque events that I'd seen the day before." Instead, the site was evicted using court possession proceedings, allowing the travellers a few days recuperative grace.

As a prominent local aristocrat and Tory, Cardigan's testimony held unusual sway, presenting unforeseen difficulties for those seeking to cover up and re-interpret the events at the Beanfield.

In an effort to counter the impact of his testimony, several national newspapers began painting him as a 'loony lord', questioning his suitability as an eye-witness and drawing farcical conclusions from the fact that his great-great grandfather had led the charge of the light brigade. The Times editorial on June 3rd claimed that being "barking mad was probably hereditary".

As a consequence, Lord Cardigan successfully sued the Times, the Telegraph, the Daily Mail, the Daily Express and the Daily Mirror for claiming that his allegations against the police were false and for suggesting that he was making a home for hippies. He received what he describes as "a pleasing cheque and a written apology" from all of them. His treatment by the press was ample indication of the united front held between the prevailing political intention and complicit national media sources, with Lord Cardigan's eye-witness account as an unplanned-for spanner in the plotted works: "On the face of it they had the ultimate establishment creature - land-owning, peer of the realm, card carrying member of the Conservative Party - slagging off police and therefore by implication befriending those who they call the powers of darkness," says Cardigan. "I hadn't realised that anybody that appeared to be supporting elements that stood against the establishment would be savaged by establishment newspapers. Now one thinks about it nothing could be more natural.

"I hadn't realised that I would be considered a class traitor; if I see a policeman truncheoning a woman I feel I'm entitled to say that it is not a good thing you should be doing. I went along, saw an episode in British history and reported what I saw."

Largely as a result of his testimony, police charges against members of the convoy were dismissed in the local magistrates courts. However, there was no public enquiry. Of the 440 travellers taken into custody that day, 24 went through the gruelling five year process of taking Wiltshire Police to court for wrongful arrest, assault and criminal damage. They finally won a four month court case at Winchester Crown Court in 1991, but received compensation almost identical to the legal costs incurred in the process. As Lord Gifford QC, the travellers' legal representative, put it: "It left a very sour taste in the mouth".

To some of those at the brunt end of the truncheon charge, the violence left a devastating legacy. Alan Lodge, a veteran of many free festivals, was one of the twenty four travellers who 'successfully' took Wiltshire Police to court following the Beanfield incident:

"There was one guy who I trusted my children with in the early 80's - he was a potter. After the Beanfield I wouldn't let him anywhere near them. I saw him, a man of substance at the end of all that nonsense wobbled to the point of illness and evil. It turned all of us and I'm sure that applies to the whole travelling community. There was plenty of people who had got something very positive together who came out of the Beanfield with a world view of fuck everyone."

The violent nature of the police action drew obvious comparisons with the coercive police tactics employed on the miners strike the year before. Many observers claimed the two events provided strong evidence that government directives were para-militarising police responses to crowd control, a view confirmed by Sir Peter Imbert, ex-commissioner of the Metropolitan Police: "A subject of concern is the move towards paramilitarism in the police. I accept that such a move has occurred." Indeed in the confidential Wiltshire Police Operation Solstice Report, released to plaintiffs during the resulting Crown Court case, it states: "Counsel's opinion regarding the police tactics used in the miners' strike to prevent a breach of the peace was considered relevant." An edition of the Police Review, published seven days after the Beanfield, also revealed: "The Police operation had been planned for several months and lessons in rapid deployment learned from the miners' strike were implemented." Such heavy handed tactics were 'justified' at the time by a farcical passage from the confidential police report:

"There is known to be a hierarchy within the convoy; a small nucleus of leaders making the final decisions on all matters of importance relating to the convoy's activities. A second group who are known as the 'lieutenants' or 'warriors' carry out the wishes of the convoy leader, intimidating other groups on site." If the paramilitary policing used on the Miners Strike was a violent introduction to Thatcher's mal-intention towards union dissent, the Battle of the Beanfield was a similarly severe introduction to a new era of intolerance of travellers, festivals and public protest.

Manufacturing A Case For Public Order Law

At the 1995 Big Green Gathering Festival, Inspector Hunt, a member of Wiltshire Police force for 20 years, told a reporter from SQUALL Magazine: "Stonehenge Festival grew too large and out of control, the Beanfield was just the beginning of the process of dealing with it. The laws that came after were even more effective." Indeed the following year saw the imposition of the Public Order Act 1986, giving police powers to break up any gathering of twelve vehicles or over. This new legislation not only provided the authorities with powers to stop convoys, it also had seriously detrimental implications for both festivals and traveller sites all over the country.

On June 3rd that year, Douglas Hurd - then Home Secretary - described travellers as "nothing more than a band of medieval brigands who have no respect for the law or the rights of others."

On June 5th, Margaret Thatcher told the nation that the British government was "only too delighted to do anything we can to make life difficult for such things as hippy convoys" . On the same day, a cabinet committee was formed to discuss new legislation to deal with travellers and festivals. Chaired by Home Secretary, Douglas Hurd, the committee was comprised of the Secretaries of State for Transport, Environment, Health and Social Security, and Agriculture.

Meanwhile, convoys assembling to celebrate that year's Solstice were chased around several counties by police, before finally finding some temporary respite on a site at Stoney Cross in the New Forest. Four days later, Hampshire Police mounted the 4am 'Operation Daybreak' to clear the Stoney Cross site. Sixty Four convoy members were arrested and 129 vehicles impounded after police came on site armed with DoT files on every vehicle. The police also came armed with care orders for the travellers' children, though a tip off had reached the camp beforehand and the children had been removed. The Battle of the Beanfield and the increasingly hostile political climate which followed, had a dramatic affect on the travelling community, frightening away many of the families integral to the community balance of the festival circuit. In 1987, people stood on the tarmac beside Stonehenge having walked the eight mile distance from an impromptu site at Cholderton. As clouds smothered the Solstice sunrise, those who had walked the distance were kept on the road, separated from the Stones by rows of riot police and bales of razor wire. As the anger mounted, scuffles broke out.

A year later the anger had tangibly increased and once again at Solstice dawn there were some who found the situation too unacceptable. This time the scuffles were more prevalent with concerted attempts being made to break through the police cordon. Secreted around the area, however, were thousands of waiting riot police and as the frustration of the penned in crowd grew, numberless uniforms came flooding down the hill to disperse the crowd with a liberal usage of truncheons and riot shields. Andy Smith - now editor of the magazine Festival Eye - finally received a £10,000 out of court settlement from Wiltshire Police in 1996 for a truncheon wound to the head received after he tripped and fell at Stonehenge in 1988.

The numbers of people prepared to travel to Stonehenge and face this treatment naturally dwindled, resulting in a concentration of those who were prepared for confrontation in defence of what was considered as a right to celebrate solstice at Stonehenge. Successive large-scale police operations backed by the Public Order Act 1986, became stricter in attempts to stop anyone from reaching the stone circle at Solstice. To this day however, there are those who hug hedgerows and dart between the beams of police helicopters in order to be in view of the Solstice sunrise at Stonehenge.

Destroying The Alternative Economy

Up until 1985, the free festival circuit had provided the economic backbone of a year long itinerancy. Traditionally the three cardinal points in the festival circuit were the May bank holiday, the August bank holiday and Solstice. Without the need for advertising, festival-goers knew to look out for these dates in expectation that a festival would be taking place somewhere. The employment of two bank holidays as specific festival times allowed workers the opportunity of attending a festival without the inevitable bleary Monday back at work. By selling crafts, services, performance busking, tat and assorted gear, travellers provided themselves with an alternative economy lending financial viability to an itinerant culture. Evidence suggests that the political campaign to eradicate festivals was aimed at breaking this economy. A working party set up by the Department of Health and Social Security published a report on Itinerant Claimants in March 1986 stating: "Local offices of the DHSS have experienced increasing problems in dealing with claims from large groups of nomadic claimants over the past 2 or 3 years. Matters came to a head during the summer of 1985 when several large groups converged on Stonehenge for a festival that had been banned by the authorities. The resulting well publicised confrontation with the police was said to have disrupted the normal festival economy and large numbers of claims to Supplementary Benefit were made."

"As soon as they scared away the punters it destroyed the means of exchange," recalls traveller Alan Lodge. "Norman Tebbit went on about getting on your bike and finding employment whilst at the same time being part of the political force that kicked the bike from under us."

In the years that followed, the right wing press made much of dole scrounging travellers, with no acknowledgement that the engineered break up of the festival economy was a major contributory factor.

Another ramification of this tactic was even more insidious and ugly. At the entrance gate to the 1984 Stonehenge Free Festival, a burnt out car bore testament to the levels of self-policing emerging from the social-experiment. The sign protruding from the wreckage proclaimed: "This was a smack dealer's car". However, dispossessed of their once thriving economy and facing incessant and increasing harassment and eviction, the break down of community left travellers prone to a destructive force potentially more devastating than anything directly forced by the authorities.

"At one time smack wasn't tolerated on the road at all," recalls mother of six, Decker Lynn. "Certainly on festival sites, if anybody was selling or even using it they were just put off site full stop."

Heroin, the great escape to oblivion, found the younger elements of a fractured community prone to its clutches and its use spread like myxamatosis. Once again traveller families were forced to vacate sites that became 'dirty', further imbalancing the battered communities and creating a split between 'clean' and 'dirty' sites. "I don't park on big sites anymore," says Lynn, who still lives in her double decker bus. "Heroin is something that breaks up a community because people become so self-centred they don't give a damn about their neighbours." Many travellers report incidence of blatant heroin dealing going untouched by police, whilst other travellers on the same site were prosecuted for small amounts of hashish. The implication of these claims were that the authorities recognised that if heroin took hold of the travelling community, their designs on its destruction would take care of itself.

"So many times people got away with it and there were very few busts for smack," recalls Lynn. "They must know smack is the quickest way to divide a community; united we stand and divided we don't."

The other manifestation of community disruption was the emergence of the so called 'brew crew'. These were mainly angry young travellers feeding themselves on a diet of special brew and developing a penchant for nihilism, blagging and neighbourly disrespect. Whilst the festival culture was healthy, the outflux of youth from the inner cities was well met, absorbed and often healed.

"To start with it was contained," says Decker Lynn. "Every family had its problems but the brew crew was a very small element around 1986, and very much contained by the families that were around. But there was large number of angry young people pouring out of the cities with brew and smack and the travelling community couldn't cope with the numbers."

The so called 'brew crew' caused constant disruption for the festivals still surviving on the decimated circuit and provided an obvious target for slander hungry politicians and right wing media. The entire festival scene regularly and incessantly painted black with the inevitable all inclusive media brush.

Raves And The New Blood

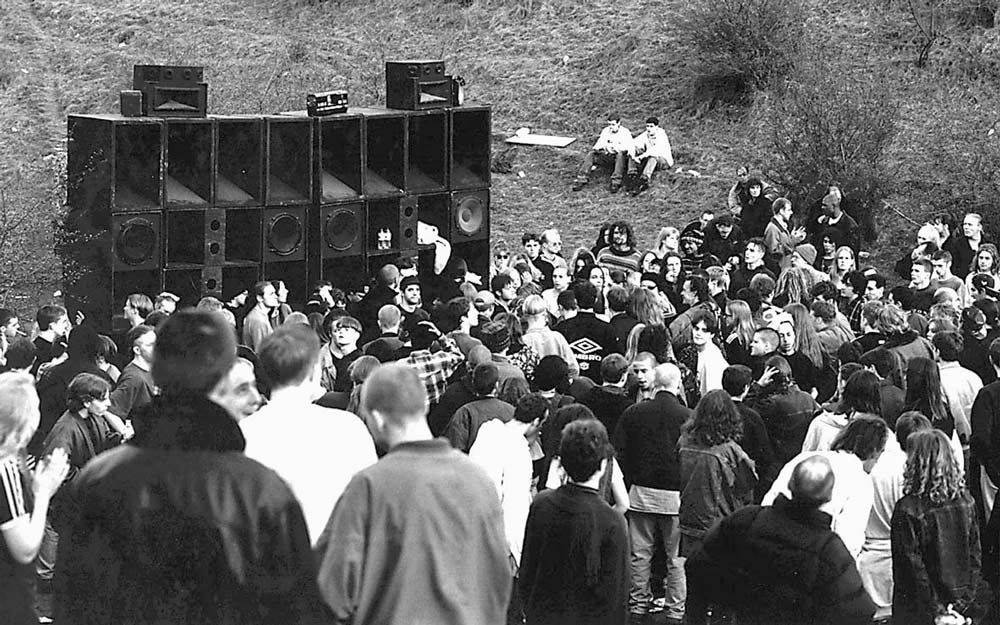

Towards the end of the eighties a new cultural phenomenon emerged in the UK resulting in an injection of new blood and economy to the festival scene. Rave parties were similar to free festivals in that they were unlicensed events in locations kept secret until the last possible moment. Such events offered similar opportunities for adventure and began attracting huge numbers of young people from the cities. Where some of these parties differed from the free festivals were that they were organised by groups such as Sunrise, who would charge an entry fee and consequently make large amounts of money in the process. Not all such rave parties were of this nature however, and the free festival scene began to merge with the rave party scene producing an accessible hybrid with new dynamism.

Once again political attention was now targeted against these new impromptu rave events, resulting in the Entertainment (Increased Penalties) Act 1990. Introduced by John Major's Personal Private Secretary, Graham Bright, this private members bill brought in massive penalties of up to £20,000 and/or six months imprisonment for the organisers of unlicensed events. Once again this legislation had a dramatic affect on the free festival/rave scene, pushing event organisation into the hands of large commercial promoters with the necessary sums required to pay for licences and policing. Indeed, a report called 'Leisure Futures', produced by market analysts the Henley Centre in 1993, gave some indication of how worried commercial entertainment businesses had become over the explosion of rave culture. Estimating that British ravers were worth a potential £1.8 billion a year to the entertainment industry, the report confirmed that rave culture was posing a "significant threat" to the market share of drinks retailers, breweries and pubs. Richard Carr, then chairman of Allied Leisure - the entertainments section of the alcohol conglomerate Allied-Tetley-Lyons - had already voiced his concern about rave culture in 1992, describing it "a major threat to alcohol-led business."

A web of mutual interests between parliamentary lobbyists Ian Greer Associates, Sir Graham Bright and one of the UK's largest alcohol-led businesses Whitbread - whose headquarters are situated in Bright's Luton constituency - opened up powerful conduits to political influence . In 1993, Ian Greer's firm helped Whitbread set up a beer club in the Houses of Parliament. With over 125 member MPs it is the largest industrial club in the palace.

As a consequence of legislation directed against raves, the nature of festival and rave promotion swung away from its community based orientation, as big business attempted to commercially harness the public's desire for adventurous festival/parties in the countryside. According to Tony Hollingsworth, ex-events promoter for the GLC and now part of a £multi-million commercial festival outfit Tribute: "The motivation behind these festivals is no longer passion, it is commerce." Relative to the people-led festivals, critics argue that the commercial festival scene now offers little more than another shopping experience, where an attendant wallet is valued and encouraged far more than participation.

Castlemorton Common

By 1992, leaked documents from Avon and Somerset Constabulary demonstrated the existence of Operation Nomad. A Force Operational Order, marked 'In Confidence', revealed: "With effect from Monday 27th April 1992, dedicated resources will be used to gather intelligence in respect of the movement of itinerants and travellers and deal with minor acts of trespass." An intelligence unit set up by Avon and Somerset Police produced regular Operation Nomad bulletins, listing personal details on travellers and regular festival goers unrelated to any criminal conviction. The Force Operational Order issued by the Chief Constable also stated: "Resources will be greatly enhanced for the period Thursday 21st May to Sunday 24th May inclusive in relation to the anticipated gathering of travellers in the Chipping Sodbury area."

This item referred to the annual Avon Free Festival which had been occurring in the area around the May bank holiday for several years, albeit in different locations. However, 1992 was the year Avon and Somerset Police intended to put a stop to it. As a result the thousands of people travelling to the area for the expected festival were shunted into neighbouring counties by Avon and Somerset's Operation Nomad police manoeuvres. The end result was the impromptu Castlemorton Common Festival, another pivotal event in the recent history of festival culture.

West Mercia Police claim they had no idea that an event might happen in their district and were therefore powerless to stop it. However, observers questioned whether it was possible that Avon and Somerset Police had not informed their neighbouring constabulary of Operation Nomad.

In the event, a staggering 30,000 travellers, ravers, festival-goers and inner city youth gathered almost overnight on Castlemorton Common to hold a free festival that flew in the face of the Public Order Act 1986 and the Entertainment (Increased Penalties) Act 1990. It was a massive celebration and the biggest of its kind since the bountiful days of the Stonehenge Free Festival.

The authorities used Castlemorton in a way which led people to suggest it had been at least partly engineered by the authorities themselves. The right wing press published acres of crazed and damning coverage of the event, including the classic front page Daily Telegraph headline: "Hippies fire flares at Police" . The following morning's Daily Telegraph editorial was headlined: "New Age, New Laws" . Within two months, Sir George Young, then Minister for Housing, confirmed that new laws against travellers were imminent "in reaction to the increasing level of public dismay and alarm about the behaviour of some of these groups." One revealing feature appeared in the Daily Telegraph following the festival at Castlemorton. Headlined "From ravers to travellers: a guide to the invaders", it profiled four individuals under the headings 'The Squatter', 'The Raver', 'The Traveller' and 'The career Traveller' - a significant early indication of what was to come. Indeed, the outcry following Castlemorton provided the basis for the most draconian law yet levelled against alternative British culture. Just as the Public Order Act 1986 followed the events at Stonehenge in 1985, so the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 began its journey in 1992, pumped with the manufactured outrage following Castlemorton. By the time it reached statute two years later, it included criminal sanctions against assembly, outdoor unlicensed music events, unauthorised camping, squatting and 'aggravated trespass' (public demonstrations). The law also reduced the number of vehicles which could gather together from 12 (as stipulated in the Public Order Act 1986) to six.

The news-manufacture used to prepare the public palate for the coming law was incessant, with media descriptions of travellers including "a swarming of human locusts" in the Daily Telegraph and "These foul pests must be controlled" in the Daily Mail.

Police Surveillance And Benefit Clampdowns

The year after Castlemorton Common, the police set up Operation Snapshot, an intelligence gathering exercise on raves and travellers designed to establish a database of personal details, registration numbers, park up sites and movements. This information was used as a backbone for an ongoing intelligence operation begun by the Southern Central Intelligence Unit (SCIU), operated from Devizes in Wiltshire and initially co-ordinated by PC Malcolm Keene. The SCIU held regular meetings with representatives of all the constabularies of Britain.

Leaked documents revealed that Operation Snapshot had estimated there to be around 2,000 traveller's vehicles and 8,000 Travellers in the UK. In the minutes of a meeting held at Devizes on March 30th 1993, the objectives of the operation included the development of "a system whereby intelligence could be taken into the control room, and the most up-to-date intelligence was to hand"..... "capable of high speed input and retrieval and dissemination of information". The meeting was attended by constabulary representatives from Bedfordshire, Avon and Somerset, Devon and Cornwall, Dorset, Gloucestershire, Dyfed-Powys, Cambridgeshire, Hertfordshire, Kent, Norfolk, Northamptonshire, South Wales, Gwent, Staffordshire, Thames Valley, Warwickshire, Surrey, Suffolk, West Mercia, West Midlands and the Ministry of Defence (Hampshire and Essex sent apologies). The police's National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS) also had representatives at the meetings, and requested that the NCIS should be allowed "to move in with the Southern Central Intelligence Unit for one or two weeks during the Solstice".

They were all asked and all agreed to provide the Southern Central Intelligence Unit with "any information, no matter how small on New Age Travellers or the Rave scene". The leaked minutes revealed the Snapshot database was initially constructed to hold one million items of information . After a short period, the Northern New Age Traveller Co-ordination Unit, designed to cover the north of Britain, was established and operated from Penrith in Cumbria.

Further intelligence information was gathered via social security offices. The working party report on Itinerant Claimants, prepared for the DHSS in 1986, advised that "in the interests of advance warning and the safety of staff, we recommend better liaison with the police."

A 1993 internal Benefits Agency bulletin headed 'New Age Travellers' and marked "not to be released into the public domain", stated: "Offices will be aware of the adverse reaction from the media following the treatment of claims from this client group last summer [Castlemorton]. Ministers are concerned that the Benefits Agency and Employment Services take all necessary steps to ensure that claims from this group are scrutinised carefully."

The bulletin reports that a National Task Force had been set up to "monitor the movements of such groups of Travellers" and to "inform relevant District managers of their approach and numbers". In the back of the bulletin is a list of telephone numbers for all the regional police contacts in both the Northern New Age Traveller Co-ordination Unit and the Southern Central Intelligence Unit. Every constabulary in the country, including the Ministry of Defence police had at least one but usually several such designated co-ordinators.

In 1995, the Benefits Agency conducted a census of New Age Traveller benefit claimants including their personal details. A leaked copy of the results suggested there to be 2000 such claimants. In July 1996, more leaked documents revealed that the Agency was once again asking regional offices to carry out a census, the results of which are as yet unrevealed . Following the introduction of the Job Seekers Allowance Scheme in October 1996, benefits may now be halted if "appearance" or "attitude" "actively militates getting a job". The implications for the further selective targeting of the traveller community are obvious.

Increased Surveillance And DIY Mutation

The extraordinary lengths taken by the authorities to annihilate travellers, raves and festivals are a testament to the treatment meted out to cultural minorities outside the acceptable hegemony.

The use of legislation, intelligence targeted harassment, benefit clampdowns and news-manufacture have been employed as a multi-tactic approach stretched out across many years.

Such strategies are often achieved without public knowledge; with the length of time over which they are employed, diffusing recognition of their mechanism and ultimate intention. What is clear, however, is that rather than seek to democratically accommodate an expanding community culture, Margaret Thatcher's government and those who replaced her sort instead to annihilate it.

However, far from disappearing as a result of these strategic clampdowns, political dissent and unlicensed communal celebrations have in fact mutated. Road protest camps are in many ways evolved versions of festival gatherings. Whilst thousands of people might attend an environmental protest rally at weekends, the very existence of an established protest depends on people living on site all year round; in benders, tree-houses, around fires, sometimes through the worst winter conditions on the frontline. Imagination has fuelled the techniques of dissent; spawning tunnels, scaffolding towers and aerial walkways as ingenious methods to prevent environmental destruction. Meanwhile, the campaign group Reclaim the Streets organise their own unique 'political parties' in audacious reclamations of the urban environment using tripods, children's play areas and sound systems for the dancers. Celebration and dissent are characteristically concurrent features of modern protest.

Other groups such as Luton's rave and social justice collective, Exodus, continue their free communal raves and housing action projects whilst facing off an incredible level of official opposition in their own locality. After several unsuccessful police operations designed to put a stop to their activities, Bedfordshire County Council have voted for a full scale public enquiry into the activities of Bedfordshire police and other agencies against the Exodus Collective.

The authorities have been none to happy to witness such ingenious and tenacious mutations, resorting to new legislative powers of intrusive surveillance to both pre-empt and undermine such dissident activities. The Security Services Act 1996 introduced statutory powers for security service involvement in the investigation of domestic 'serious crime', whilst the 1997 Police Act gave police similar statutory powers of intrusive surveillance. The definition of 'serious crime' used in both these pieces of legislation includes "conduct by a large number of people in pursuit of a common purpose". The implications of this loose definition for public protest and celebration are obvious.

Along with the Interception of Communications Act 1985, this now allows the police and security services to use intrusive surveillance devices to "safeguard the economic well-being of the United Kingdom". Indeed, a publicly available brochure, published by MI5 in 1995, listed the safeguard of "those elements of commerce and industry whose services and products are of critical national economic or civil importance" amongst its responsibilities.

The arms industry, the fast food industry, the road building/car industry, the nuclear industry, the alcohol industry and the pharmaceutical industry are amongst those who are both powerful corporate lobbies and the targets of recent political protest. Up until March 1997, the Department of Transport admit paying out £2.2 million pounds to Bray's Detective Agency to gather intelligence on road protesters . The Security Services Act and Police Act pave the way for both MI5 and the police to take over this role. Meanwhile, amidst the tidal wave of previously hidden information revealed in court during the mighty McLibel trial, came news that Special Branch freely offered to provide McDonald's with information about persons regularly attendant at anti-McDonald's demonstrations . Given that the 1984 Home Office guidelines for Special Branch state: "Access to information held by Special Branch should be strictly limited to those who have a particular need to know. Under no circumstances should information be passed to commercial firms or to employers' organisations", no-one is left in any doubt that the rules are there for breaking. Indeed, the four women from the Ploughshares movement who gained entry to a British Aerospace Factory at Warton in Lancashire in 1996, broke the rules by smashing the windscreen of a Hawk fighter jet bound for Indonesia. They won their subsequent court case with the argument that their action, though criminal damage, was carried out to prevent the greater crime of the Indonesian government's genocide of East Timorese. An ex-policewomen connected with the Ploughshares group also revealed that Special Branch had offered her £200 a week to provide information on individuals connected to the movement. Whilst the Labour Party chose not to oppose the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act, they actively supported both the Security Services Act and Police Act.

Of the few festivals which now remain on a once flourishing circuit, Glastonbury Festival still retains substantial elements of festival culture not present at the more prevalent and community-devoid commercial events like Phoenix, Reading and the Tribal Gathering. In the so called 'green field' section of Glastonbury festival you'll still find a flourishing multitude of well represented campaign groups interacting with the cultural celebrations.

If there is one overriding impression asserting itself from this brief history, it is that despite incredible opposition, imagination constantly evolves new ways of thriving. The freedom to voice dissent in this so called 'democracy', the freedom to live life rather than swallow it, has been the target of forcible attempts to homogenise both consent and culture. Despite the deployment of insidious measures of annihilation, unofficial celebration and conscious dissent both survive and thrive using the greatest talent it has to hand - ingenuity. Fortunately it is still not possible to legislate against such resource.

The Observer 9/6/85 'Operation Solstice' Channel Four 7/11/91 made by Neil Goodwin and Gareth Morris Written statement by Tim Malyon 4/6/85 Interview with Lord Cardigan - SQUALL 14 Autumn 1996

'The case against para-military policing' by Tony Jefferson (pub Open University Press 1990) Police Review 7/6/85

Daily Telegraph 6/6/86

Hansard 5/6/86

Times 6/5/86 and Daily Telegraph 6/6/86

'Nomadic Claimants - Report of Working Party' Department of Health and Social Security HQ9RD9) March 1986

Independent 17/8/92

The Observer 20/10/96

Force Operational Order 36/92 - 'Operation Nomad' issued by Chief Constable of Avon and Somerset Constab. "in confidence".

Daily Telegraph 26/5/92

Daily Telegraph 27/5/92

Daily Telegraph 27/5/92

Daily Telegraph 7/6/93

Daily Mail 27/5/92

leaked minutes quoted SQUALL 14 Autumn 1996

Income Support Bulletin 24/93 Benefits Agency ("not for public domain")

The Guardian 19/7/96

SQUALL 9 Winter 1995

'The Security Services' HMSO 1995

Hansard 17/3/97 Col:417

SQUALL 14 Autumn 1996

SQUALL 14 Autumn 1996

Related Articles

Wally Hope - A Victim Of Ignorance - the life and death of one of the founders of the Stonehenge Free Festival - Squall 11, Autumn 1995

Culture-Cash-In On Raves And Festivals - a look at the so-called 'new age entrepreneurs' cashing in on the current political climate for festivals - Squall 10, Summer 1995

There's No Such Thing As A Free Festival - Sam Beale talks to some modern day festival organisers about how to sow the festie-vibe in the harsh nineties - Squall 14, Autumn 1996

Recreational Drug Wars - the battle waged between vested business interests and rave culture - Squall 12, Spring 1996

Recommended Viewing

'Operation Solstice' - a film produced for Channel Four about the Battle Of The Beanfield - co-directed by Squall's own Neil Goodwin - is viewable on YouTube - click here