Radio Pirates

Seizing the airwaves for the love of music, pirate radio ducks, dives and thrives in Manchester. Ursula Wills-Jones tunes in to pirate talk.

Squall 13, Summer 1996, pp. 38-39.

Better than drugs! It’s free, it’s fun, and it’s completely illegal. Usually dealt out of the inner cities, it comes in flavours to suit all tastes, has no known side-effects, and you can’t be busted for possessing it. Well, not unless you get caught red-handed with all the turntables and transmitters, that is.

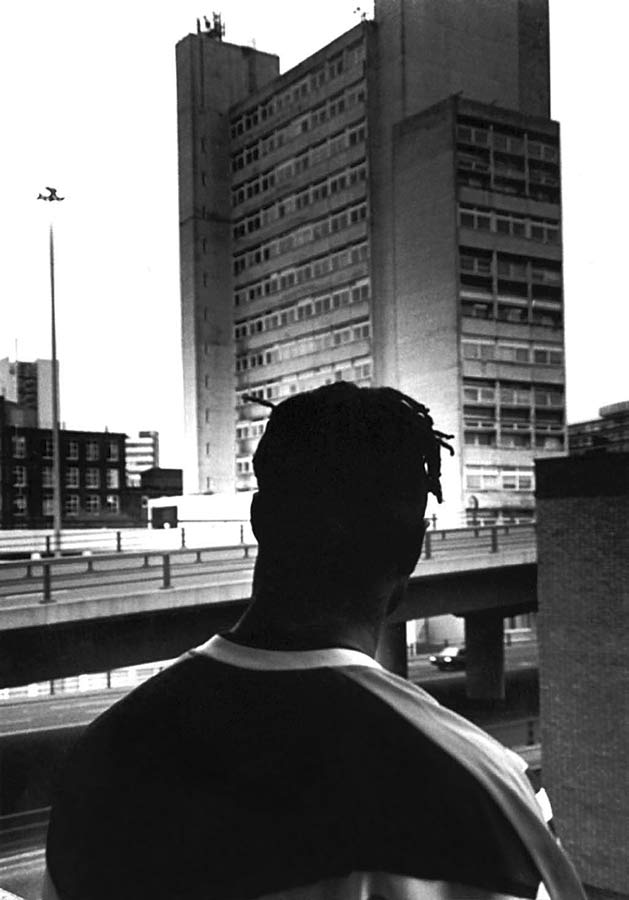

Yup, it’s a pirate radio station. Tune into local commercial radio stations anywhere and you notice they all sound remarkably similar. The same anodyne diet of chart hits, ‘lite’ news reporting and inane chat. They could be coming from anywhere. But tune into a pirate and you know where you are: in our case, within ten or fifteen miles of South-Central Manchester. ‘South-Central’, or more specifically the tower-blocks in and around Moss Side, hide half a dozen pirates. Between them they broadcast soul, reggae, R’n’B, hip-hop, jungle, and ragga.

“All these other stations, they’re ALL playing the same music,” moans T2Bad, station head at Soul Nation. He set up Soul Nation, one of the larger and more professional stations, in the summer of 1993. “There’s a couple of soul shows at the weekend, one or two jungle shows, one or two hip-hop shows, and they reckon, well, that’s enough for you niggas and everyone else who wants to listen to it. It isn’t! Soul Nation’s proved it. I’ve not got this station saying that I’m trying to entertain people with this colour skin. I’m trying to entertain people - period. Our station’s brought people together.”

Soul Nation’s program of solid soul and R’n’B might not be to everyone’s taste, but it certainly is to somebody’s. He reckons the station was picking up half a million listeners a week at it’s peak. Soul Nation are after the holy grail of pirate radio, a legal licence. They’ve been busted once, losing all their equipment, but now they’re up and running again. In a more reasonable world, T2Bad should hardly be the kind of guy to set terror into the hearts of the establishment. Bright, ambitious, and articulate, he shudders like a true Thatcherite at the suggestion that he might be providing a community service. “If a black man says ‘the community’ everyone thinks Moss Side. My community is the North-West, people like you, him, me, anybody.” He says, gesturing towards the smartly dressed people in the bar where we’ve met.

Nevertheless, he’s something of a wanted man. In fact, he believes that the station’s success is what scares the official stations. “When we were taken off air, it was said to us in a very official capacity, by a high-ranking police officer to a club manager, ‘tell Soul Nation they’ve got to downgrade their operation, because they sound too good, and it’s getting noticed by the right and wrong people’. The right people are your white ABC1 middle class people. The legal stations start thinking this is traditionally our territory - these guys have gotta go. ”

Other stations, however, are quite happy to talk about the community. “The commercial stations aren’t giving people in the community what they want to hear. We’re not getting in the way, because at the end of the day they’re not playing our music.” Says Dee, a DJ on Love Energy, another large station mixing hip-hop, soul, ragga, and jungle.

Unlike T2Bad, Dee is shy and diffident. He says he doesn’t earn anything from doing the radio shows, but it allows him to plug his work as a DJ outside the station. “Most of what we play, they won’t play on the commercial stations because it’s too underground. We’re there to breach the gap.”

Dee and Emperor from Love Energy don’t exude the same air of confident prosperity as T2Bad. “We’re all unemployed” says Emperor, “we’ve not got anything else to do. It just takes up all our time. It’s what we want to do, isn’t it?” Still, everyone agrees that the pirates are not just about broadcasting to the ghetto. It’s about broadcasting to anyone who is into the music.

No-one at the pirate stations relishes their illegal status. On the other hand, few would be interested in going legal unless they could continue broadcasting the same styles of music. Dee says that if he was offered the chance to play what he liked on a legal station, he’d take it. “I’d go for it, yeah. I’d get paid,” he says, with a long-suffering expression.

Emperor and Dee say they can remember the first pirates setting up in Manchester in the mid-80’s. “I think pirate stations are always gonna be around.” says Dee. “If we eventually go off the air, somebody else will come on.”

If the range of music broadcast by the pirates is pretty diverse, individual stations tend to stick much more closely to one or two types of music. “We don’t broadcast, we narrowcast. We know what we’re good at, we know what we’re capable of, and we stick to it. Everyone on my station is doing it for the love of it,” says T2Bad.

In theory, the artists whose tracks are played on the pirates are losing out, because no-one receives any royalties. In practice, however, they probably benefit. A number of recent big-selling tracks like 2Pac Shakur, the Fugiz, and Mark Morrison are likely to have been receiving far heavier airplay on pirates around the country than on official stations.

"It's not the DTI you're fighting it's the Government. Whoever controls the media, controls the people, right?"

Emperor and Dee say they put in their own money to keep the station going. Otherwise, pirate radio gets it’s funds from a variety of sources, including advertising and club nights.

No business will actually admit to paying the pirates for advertising, claiming rather unconvincingly that it’s just a matter of discounts here and there. Cari-Afro, a city centre shop selling hip-hop style clothes advertises on Love Energy. Jo from Cari-Afro admits that the adverts do bring in business. Just last week, she says, a woman who had just moved to Manchester came in, saying she had heard of them on the station. She spent more than £500. “Let’s face it, the kind of people who buy this kind of gear, they’re into a certain kind of music, and you don’t get that on Piccadilly FM,” says Jo. Not all the businesses advertising on the pirates are necessarily aiming at the young and hip. Love Energy carries adverts for washing machine servicing and car repairs, Soul Nation for insurance, and Frontline for Caribbean takeaways.

The number of adverts carried by the pirates is considerably fewer than those carried by commercial radio. They also tend to be for different things: instead of flaunting a consumer dreamland of fast cars, fancy holidays and financial deals they promote the ordinary and the necessary: food, clothes, music, car repairs and so on. For local black businesses, they provide an affordable and neatly targeted outlet for advertising.

The adverts are just one of the reasons why pirate stations manage to sound more human than their national or commercial equivalents. Somehow, listening to pirate radio can be remarkably comforting. It’s sunk deep into a geographical space that makes sense to you. The voices that come to you are only a couple of miles away. If it’s raining where you are, you know it’s raining where they are. They sound ordinary and friendly, a million miles away from the slick egomaniacs who dominate stations like Radio One. Links are fluffed, records slip, presenters turn up late, but it all adds to the impression that it’s a real person talking to you, not a machine.

The Department of Trade and Industry doesn’t really care about any possible benefits pirates might bring. They say they interfere with emergency services’ radio signals and fair broadcasting competition. T2Bad disagrees: “All I’m doing, I’m just offering fair competition. I thought that was what this Government was all about, innit?” He laughs, and describes how the station got raided. “The DTI turned up in force with the police. The police are only there to stop any breach of the peace taking place, but in our case the DTI turned up wearing flak jackets. They must have thought that some big amount of grief was gonna go down or whatever.”

In 1993-4, there were 570 raids on pirate radio stations. Like many other cultural activities which are frowned on by the authorities, the penalties for running a pirate radio station were upped by the 1994 Criminal Justice Act.

It’s easy to suspect that the reasons why the authorities actually clamp down on the pirates are rather more complex that the officially stated one. For one, it’s a strong and vibrant form of cultural expression which, like rave culture, doesn’t conform to Major’s ‘warm beer and village cricket’ vision of Britain. It’s incomprehensible to white, middle-class, fifty-something England, and thus, deeply suspicious. Furthermore, it represents a picture of life in inner-city Britain which is a long way from the one the Daily Mail would like to depict.

Listening to any of the stations coming out of Moss Side, you’re struck by just how normal life sounds. The world they present is not one of guns and crack, but an ordinary one of food, relationships, and malfunctioning washing machines.

In effect, it’s the ghetto speaking with it’s own voice - but it’s not saying what it’s meant to say. T2Bad, for his part, is intelligent enough to realise that the reason his station is “public enemy number one”, as he puts it, goes beyond the threat of competition. “There’s a lot more to it than that. A few months back someone said to me what you’ve got to realise is, it’s not the DTI you’re fighting, it’s the Government. Whoever controls the media, controls the people, right? The people directly react to what the media tells them. It shapes everyone’s lives, it shapes people’s ideas. They’re not going to let somebody walk in and take a piece of it.”

Stop Press

Four pirate stations in Manchester have gone off the air after their transmitters were confiscated in raids by the DTI. However, most stations are expected to be broadcasting again within a few weeks. Soul Nation, Frontline, Love Energy and Sting FM all lost their transmitters, which are located separate from the stations’studios. The raids follow DTI sweeps on pirate radio stations in London and Bristol. Pirate radio heads believe the raids may be linked to Euro ‘96: clearing the airwaves so that the legal broadcast media can gain maximum advertising impact during the competition.

Related Articles

Pirating The Airwaves - Pirate radio making waves against oppressive regimes - Squall 14, Autumn 1996

Active On The Airwaves - Airto Coral catches up with Interference FM, the pirate politico's - 2000