Poverty Knocks

Britain's inequitous class system is dead and poverty no longer exists. At least according to Prince Edward and Peter Lilley. Jim Paton begs to differ...

Squall 13, Summer 1996, pp. 30-31.

Free advice has been plentiful lately. We’ve had the wisdom of Peter Lilley on poverty (it’s only relative; let them watch videos), then the Arrogist Formerly Known as Prince Edward scythes through the complexity of Britain’s class structure (which, he says, no longer exists), explaining the abundant opportunities available to us all.

The stunning lack of relevant experience available to these glib pontificators was pointed out, but columnists in liberal newspapers are often not familiar with the realities of living on the edge themselves, and it showed. For them, poverty is something to be researched, analysed, maybe agonised over, but never experienced. As a result, they largely conceded Lilley’s delusions about relative and absolute poverty without a whimper. A person defined as poor in this country, the pundits averred, has a water supply, clothes to wear and food to eat. They probably have a clapped-out TV, or even - manna from heaven - a video! Also, when compared with a landless urban refugee in Brazil or Mozambique, or a Sahel nomad, people in Britain are only relatively poor, we were told.

So the attack on Lilley was effectively confined to his neglect of “social exclusion”, ie in our affluent society, a poor person may have the essentials of life but is excluded from full participation. To quote some of the examples cited, “socially excluded persons can’t pay for their children’s school trips or take them to McDonalds”.

What was loftily unseen by the commentators and their theories of relativity is the growing, gnawing presence of what - in anyone’s book - can only be called absolute poverty. People who regularly go hungry, sometimes for days on end, so their children can eat and survive in absolute, not relative, poverty. The situation is common, but those facing it don’t write many letters to The Guardian: 45 pence pays for a pound or two of spuds.

The boundaries of absolute poverty vary from one society to another, depending on factors such as climate and what you can scavenge for nothing or next to it. In Britain, discarded TVs, videos and many other consumer goods can be had from skips and tickled up. They signify very little. What can’t be scavenged so easily is the fuel needed to stay warm through a British winter. Lilley’s “safety net” should fool nobody. If you’re old or ill as well as poor, you dread the winter and may not survive it. That’s absolute poverty. A corner flat in a Newcastle tower block, or a place where the water some other people don’t have is running down the walls, costs a lot more to heat than a flat in the middle of a London mansion block. That’s just tough. Since the “safety net” isn’t relative, the result is absolute poverty.

Then there’s housing. The lack of it is both more visible and more intractable than the lack of food or fuel, yet homelessness apparently struck none of the pundits as one of the prime examples of absolute poverty. Without a home, a video is academic. The housing deficit is spiralling, with around a million new homes needed over the next 10 years. Even the Government admits to at least 650,000, but their main response has been to organise a coterie of well-salaried housing associations to borrow more and more money from their friends in the city, whilst restricting access to homes for those who are poorest even further. This produces only a fraction of the housing needed, and some of it is not really new but simply buildings tarted up with borrowed money after the eviction of even more disadvantaged people. They also trumpet private renting as a housing provider, but this is actually a mechanism dragging people into poverty, whilst the insecurity and stress it engenders saps the spirit and breaks some people completely.

If you're old or ill as well as poor, you dread the winter and may not survive it. That's absolute poverty.

It is heading for collapse anyway. If the present pick-up in the housing “market” continues, it will once again become more advantageous to sell homes, rather than rent them, and thousands will be evicted. New Labour promises no more than minor tweaks to the same old nostrums. In a year or two, no doubt, they’ll be the ones telling us that people skippering or living on the streets are only “relatively” poor.

However, one factor is relative. It’s pointless to consider poverty without taking stock of what opportunities we have to improve our situation by our own efforts. This is where young Prince Eddie couldn’t be more wrong.

In European countries - and this one in particular - the opportunities for self-help action to improve our circumstances by our own efforts are painfully few and always meet official opposition. Not only is there a battery of planning laws and a hostile bureaucracy geared to serving the needs of business and government at the expense of homes and other needs, but self-help is being increasingly criminalised in an attempt to drive the DIY culture off the map. They’ve even set the Anti-Terrorist Squad on us now!

Contrast this with the situation in many of the countries where nobody would dispute there is absolute poverty. The very poorest people in many cities, who have no other option but to live on the streets, often start where they are and with the little they’ve got and build their own housing on land nobody else is using. At first, it is flimsy and inadequate. Certainly, after the police have torn down their homes, but when people persist the state often sees no point in spending more and more money to prevent people providing for themselves what it cannot. From that point on, people begin improving their homes over time. A study of the creation of barriadas in Peru in the ’60s estimated that, on average, it took ten years to progress from little more than screens of matting to soundly constructed houses with electricity and sewerage. This was achieved not by the investment of money - there was hardly any - but by the investment of peoples’ time, energy, ingenuity and co-operation.

Settlements of this sort have multiplied in recent years, and millions are involved. They mean that marginalised people who would be burning their cities if they were in Europe or the USA, are building instead. Far from suffering “social exclusion”, the experience is one of intense dialogue and the forging of a strong collective spirit of justified pride as settlements are developed and administered by the people who have created them.

In this country, squatting has been a much more slender thread of DIY action down the years, well before anyone even thought of the term. People have not only solved their own housing problems but have sometimes gone on to widen their lives, and their communities in a bewildering variety of ways.

Since the ’60s, squatting has provided an almost unique meeting ground where some of the most disadvantaged people around have joined with others who’ve had - at least for now - very little money, but lots of energy and ideas. At its best, squatting has enabled us to wrest more control over our circumstances and taught us how to respect and work with each other. It has done more for the common good than bucketloads of council planning, “community development”, social work or law enforcement.

This year is the 50th anniversary of probably the biggest squatting movement ever in Britain - the camp squatters of 1946 - who took over disused airfields and military bases in large numbers, improvising an organisation that forced State recognition of people’s needs and the common sense of how they had set about meeting them. When State opposition and repression failed, all they could do was start co-operating with what was going on! Like more recent squatting movement, the 1946 squatters comprised a very wide range of people, “from tinkers to academics” as one commentator observed.

The DIY culture of the ’90s is actually in an old - and increasingly recognised - tradition. It’s as much about building what we need as stopping the DoT building what we don’t need. One of the things we need most is land to live on; homes, in other words. We know we can build them if we can prise out the chance to get on with it. We know we can do a lot more for pennies than the state can for millions. Above all, we can build communities which are good places to live, which enhance wider neighbourhoods and enrich people’s lives. Yet huge areas of vacant land in all our cities, much of it blighted in the ‘80s, are now being snapped up again by developers for superstores, retail warehouses and homes which only the rich can afford - the very land which is the only hope for homes for those who don’t have them, as well as for many other pressing needs.

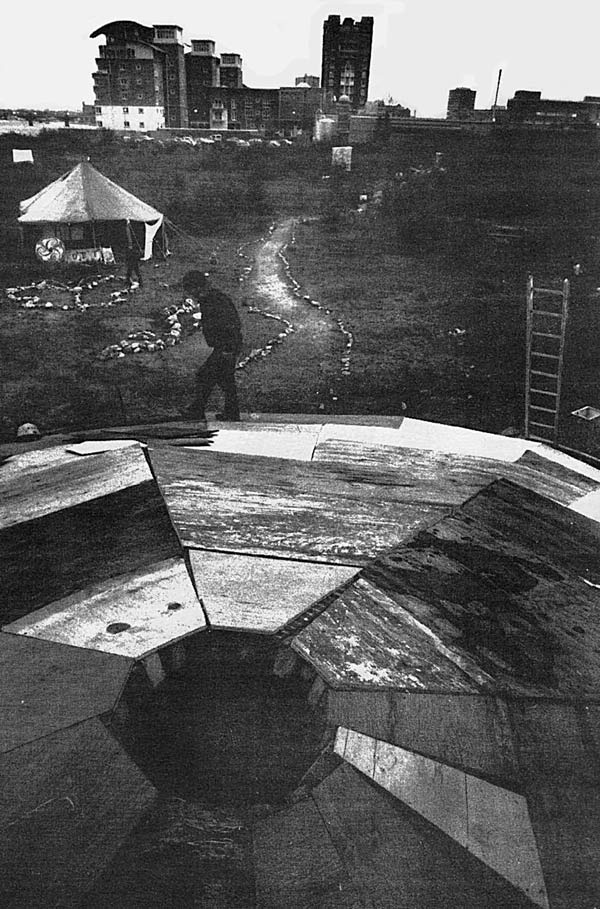

The recent Land Is Ours occupation in Wandsworth took an opportunity we’re not allowed to have in reclaiming one of these critical urban spaces and demonstrating practical ways of meeting those needs - needs which fall beneath the gaze of Peter Lilley, as he spies homelessness from distant foreign shores.

What about Lilley n’Eddies’s other pals at the levers of power and influence? The UK was not only a signatory to Agenda 21 at the 1992 Rio Earth Summit, but an apparently enthusiastic one. It says governments should have: “...an enabling approach to shelter development and improvement that is environmentally sound”. And it gets more specific: “All countries should as appropriate, support the shelter efforts of the urban and rural poor, the unemployed and the no-income group by adopting and/or adapting existing codes and regulations, to facilitate their access to land, finance and low-cost building materials and by actively promoting the regularisation and upgrading of informal settlements and urban slums as an expedient measure and pragmatic solution to the urban shelter deficit.”

Now take a deep breath. The actual point of Lilley’s “relative poverty” rant was to say the UK doesn’t need to bother about any of that! We know different and we’re getting on with it.

All we can say to Lilley’n’Eddie etc. is what the Diggers said to the government when they started their pioneering occupation in 1649:

“We are made to hold forth this Declaration to you, the great Council, that you may know what we would have and what you are bound to give us by your covenants and promises, and that you may joyn with us in this work and so find peace. Or else, if you do oppose us, we have peace in our work and in declaring this report and you shall be left without excuse.”

Related Articles

Aggracultural Trespass - Squatters occupy wasteland at Wandsworth on the Thames owned by Guinness - Squall 13, Summer 1996

50th Anniversaries - And All That - 50 years after VE Day, and therefore 50 years of the post-war squatting movement in Britain. By Jim Paton - Squall 10, Summer 1995