Pedal For The Planet

An expedition around the world? Nothing unusual about that these days. An expedition cycling round the world, crossing both the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean in a 30ft pedal boat? Now that’s unusual. And if you were to learn that the expedition’s co-ordinating office is in a London squat and that it has no money whatsoever in its bank account, you might be thinking - ‘They’re nutters’.

But wait up with the hasty diagnosis because as SQUALL goes to print, Jason Lewis and Steve Smith are on the verge of landing on the shores of Florida, having pedalled and weathered a three and a half month Atlantic crossing from Portugal. In the flurry of activity that preceded their departure, Jim Carey grabbed a few words with them and their support team.

Squall 9, Jan/Feb 1995, pp. 42-44.

“The idea was originally conceived by my colleague Steve, in Paris about three and half years ago,” recalls Jason. “He was working as an environmental consultant at the time. I think he was pretty manicked out actually - not a lot of friends. He went a bit cuckoo and thought this idea up.”

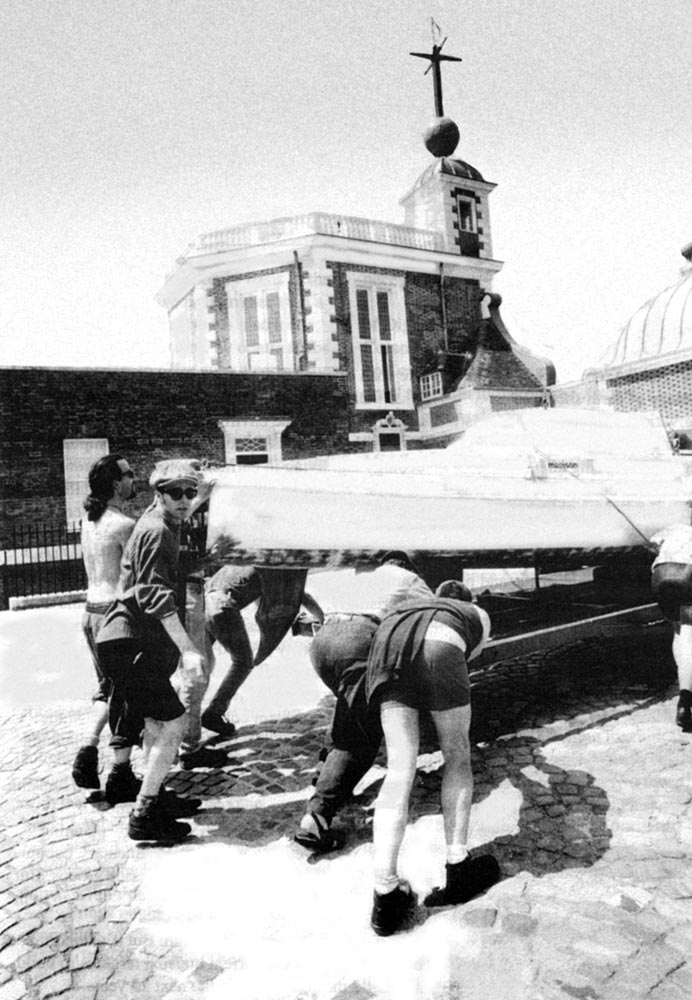

Three and a half years later, after gargantuan amounts of blagging, determination, synchronicity and ingenuity, that ‘cuckoo’ idea is being realised. The Pedal for the Planet Expedition set off from the Greenwich Meridian on July 12, crossed the English Channel from Rye Harbour in Sussex, cycled down through France and Spain to the Algarve in Portugal and then pedalled off into the Atlantic Ocean on October 13th, heading for Pier 61 - Fort Lauderdale Harbour, Florida, USA.

“A mate of mine who works in a genetics laboratory, says we’re about 50% nature and 50% nurture, and it’s that 50% nurture that really inspires me,” says Jason. “You’ve been given a load of putty clay in your hand, so let’s see what you can make of yourself.

“It's really easy to get defocused and lulled into this wishy-washy existence. It takes a good snap and kick up the backside for me to think - hang on! God, I’ve been caught napping again - and then to try and maximise life.”

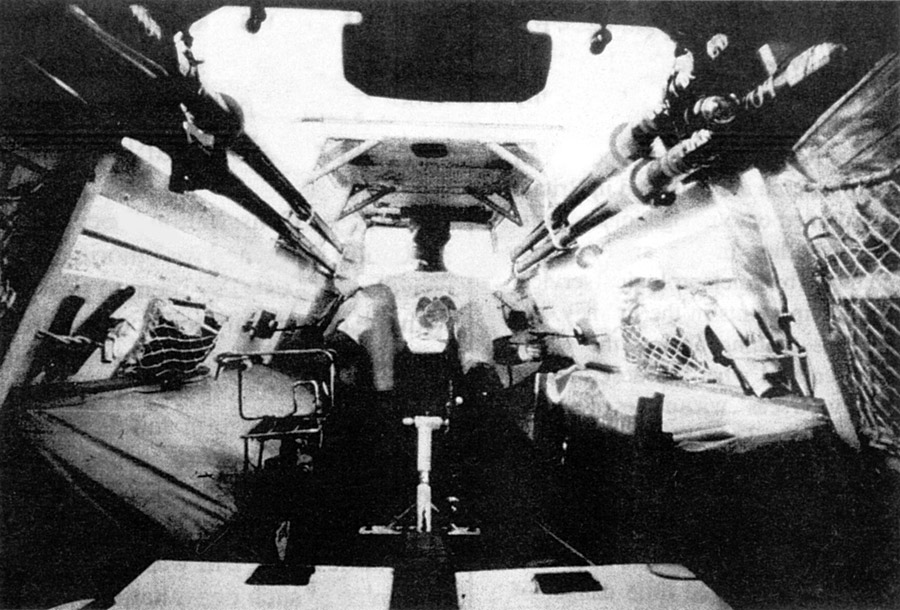

The 30ft pedal-boat ‘Moksha’ (Sanskrit for Freedom), was specially built at Exeter Maritime Museum and, weighing only 350 kg, seemed too flimsy a craft to be dealing with the 40ft+ waves that the world’s largest oceans will throw at it. Waves, however, are the least of the problem.

“The boat is self-righting,” explains Steve. “The only thing that can go seriously wrong is if we run into a super tanker ‘cos these seas are full of international shipping. We have 3 knots in this boat - hundreds of thousands of tonnes of steel coming at you at 20 knots is my worst fear.”

So far though, the boat and its crew have safely crossed both the English Channel - the busiest shipping lane in the world and, as SQUALL goes to press, the Atlantic Ocean.

Between the conception of the ‘cuckoo idea’ and the expedition’s departure, has been three long years of preparation. This has seen Jason and Steve thoroughly immersed in a myriad of diverse activities including sponsorship, promotions, boat-testing and media.

“It’s been a fucking nightmare to be honest,” snorts Jason. “The whole business of raising sponsorship and the media is such a wolf pit. I’ve found that I’ve had to put on this Trojan horse mentality - cloak and dagger. It’s been interesting and I’ve learnt and developed more tools and skills - I know how the PR and sponsorship world works and I know that I really don’t want to have anything to do with it.”

Fortunately, despite an erratic team sheet through-out the years of preparation, the expedition managed to recruit a film-maker/cameraman on the final furlong of the preparation for departure.

Kenny Brown had been squatting in London for over six years, shooting home movies and helping to organise several squat cinemas:

“When I met Steve and Jason, they were both quite strange. They were thinking - ‘What’s he like?’. They didn’t have a CV of all the adventures they had done, it was more like: ‘we are doing this’ full-stop. I had planned an expedition going across Russia on bikes but that fell through. I’d spent too much time dealing with maybes - people promising things that aren’t happening. Meeting people that are determined to pull things off is much more worthwhile.”

Also recruited for the first leg of the trip was another London squatter, Martin Gascoigne. His job was to transport the pedal-boat from Greenwich, down through Europe, stopping in Paris, Madrid and Lisbon for press calls.

“The expedition concords with quite a lot of things that are priorities for me. It’s bicycle centred, I like their general ‘get up and do it’ attitude, and it was an ennobling idea to see in action,” says Martin, a keen cycle enthusiast.

The aim of the expedition, besides the personal challenges involved, is to inspire the world with the potentials of pedal power and, by visiting schools on their way round, inspire children with a sense of adventure.

“The green angle of the expedition, is very simply that it can be done,” says Kenny. “There’s no power involved except for human power. The Pedal for the Planet expedition could have been done hundreds of years ago. You don’t need loads of technology - very simple ideas can move us forward. It’s about changing people’s habits. It’s not taking a car when you go shopping; it’s people realising they have choices rather than presuming something is a necessity. That will change more things in the world than any laws.”

“Moving away from the motor car is inevitable now,” adds Martin. “I think bicycles have a lot to say on a number of different levels, both in terms of economy and in terms of people’s health. So this is a very direct way of kicking things off’

For Jason, the school visits are an important part of the trip; a part of same questioning of pre-set ideas that drove them to attempt the journey in the first place.

“Me and Steve want to experiment with ourselves. We’re sick of sitting around like do-dos in this society just being told what to think and how to behave. For us the whole trip is very much a questioning procedure. And we want to pass on some of that to the children. Try and instil a mentality of not just lying down and saying ‘OK, that’s the way I’ve been told, so that’s the way it is’. Not just taking it for granted but seeing what’s best for them and the whole system they’re living in.

“But I know all the kids won’t be leaving the class going: ‘God I’ve really got to re-evaluate my life now’. Mostly they’ll identify with the boat, they’ll want to know about the sharks and the really bad storms and how you’re gonna have a crap - anything that’s different and exciting. If they come away with even a little bit of the reasons why we did it, even if they think: ‘crazy lunatics in a boat’, then that’s great in itself - you can’t ask much more than that. I think it will fill them with a bit of adventure and that will be a good thing.”

The enormity of the undertaking and the small number of people involved, has meant that the team have had to do a lot of lateral thinking to overcome the difficulties of the expedition. Certainly the expedition has some well known official patrons, including Sir Ranulph Feines, Jonathon Porrit and The Duke of Gloucester. It also has some material sponsorship such as bicycles, army rations and a satellite transmitter. Financial sponsorship on the other hand has not been forthcoming.

Some money was raised via an idea dreamed up by Steve’s dad; offering to put the names of anybody who gave a tenner onto the hull of the boat. SQUALL’s name, along with about a thousand others, forges through the seas at this very moment. This brought in £10,000 which was inevitably spent in no time at all. The biggest single cash injection of the expedition so far actually came from a benefit night held in a London squat two weeks before they left. Pooling culinary and musical skills and throwing open their doors for a small admission fee a household community of London squatters managed to secure the £1000 necessary to get them to Portugal.

“I can’t think of anybody in that house that didn’t help the expedition,” says Kenny. “Everybody did something, whether it was packing the van at five in the morning ‘cos we had to rush off to a press call, to sitting up half the night emptying out bags of food and sorting out the packs for the Atlantic. That just wouldn’t happen in any other situation. There is a support from the immediate community - you wouldn’t have that if it was a rented office or a rented house. It’s part of the lifestyle of squatting if you like, being with other people and doing things with them rather than everyone separated.”

The same household gave over a room to the Expedition for use as its main office during the final month before departure. Satellite co-ordinates of the Atlantic crossing are still plotted onto the Atlantic Navigational charts that stretch across it walls.

By the time they reached Portugal, the benefit-party money had been spent. Three hundred and fifty miles off the Portuguese coast, Jason, Steve and the good ship Moksha called in for minor repairs at the island of Madeira with absolutely no money. By phoning someone he’d met in Portugal, who had a son that lived in Madeira, Kenny was able to arrange for someone to meet and sort them out with marina space, equipment and hospitality. Such a talent for pulling things off and making things work, is something that has been cultivated in everyone involved in the challenge of running such a major expedition almost exclusively on ingenuity and determination.

“Getting down to Portugal was an expedition in its own right,” observes Kenny wryly. “A four man team and a boat across Europe on £80 a week!”

The one tonne trailer that carried the boat through Europe had been blagged, borrowed but definitely not stolen, from the ominously named ‘Heavy Boat Squad’ of the Metropolitan Police; the van pulling the trailer was borrowed from a parcel delivery company. The food taken on board for the Atlantic crossing consisted of 5 years-past-the-sell-by-date army rations Jason had wangled through contacts he’d made with the army.

“It’s been blag, blag, blag all the way,” laments Kenny. “I’ve learnt a lot about how to make things work, one of those being sheer determination.”

They also leave hind several large debts; a fact Steve was well aware of just before leaving Portugal:

“If you really want to be mentally and physically free then the last thing you want to do is invent a round the world expedition which will cost hundreds of thousands of pounds,” says the very matter of fact Steve. “What has become a very serious external influence is the fact that we still owe so much money. When the shit hits the fan, the thing that will keep me going is the fact that I am indebted to people. So my priorities are firstly to repay my family and friends financially and secondly because there are now thousands of people who would love to see us do it.”

The hope of the expedition when it reaches America is that, having proved they can stay alive and get across the Atlantic Ocean, sponsors will be far more forth-coming.

“Any expedition gets more attractive to sponsors the closer it gets to completion,” says Kenny.

Despite the financial millstones and insecurities hanging round the expedition’s neck, the mental attitudes of those involved remains firmly fixed on success.

“I feel remarkably calm and composed,” said Steve just prior to cycling off into the Atlantic. “People around me are feeling more nervous than I am apparently. I think I’ll be scared the first time I experience bad weather because I’ve never been at sea in very bad weather in a boat this size. But we won’t be panicking. I’m confident that we’ll both be quite business like about it.”

“I don’t really get worried about crossing the Atlantic,” adds Jason. “What I find more worrying is sitting around not doing it. The human body is a lot stronger than we give it credit for - yeah, at the end of the day you might die but then so fucking what, you could die crossing the street - run over by some lunatic pizza express delivery man on a mission.”

There were some sobering reminders however.

“I think once I start out it will hammer itself home a bit more,” says Jason. “The other day, my dad was sitting there after tea and he said ‘so have you made a will yet’. So I said ‘what do I want to make a will for - I’ve got nothing to leave anyone’ and he said ‘well, we just wanted to know in case anything did bob back - what to do with it, whether to burn or bury it’ - Like my right foot or something! That was a big bucket of cold water over my head. My strawberries and cream came flying out of my bowl.”

But for Jason, the philosophy of life overrides the fear of death.

“Not a lot of people have the privilege to get to that point and I think that’s when you really start living to the maximum and you say ‘yeah I’m alive!’. When you’re faced with not having it, that’s when you really appreciate it.”

Regular satellite updates of their position are collected in Britain and plotted onto navigational charts. The weather in the area is then predicted by a meteorological service. At certain points in the journey, sea currents running against the winds have created what are described as ‘confused seas’, with waves of around 30ft or more. There have been several occasions when they have been blown back miles.

Despite this, progress has been good, with an average rate of around 45 miles a day and little danger of them running out of their 106 day rations, especially if the good fortune they had at Christmas continues.

On the Yule day itself, Steve and Jason came across an American Cable Laying boat anchored two thirds of the way across the Atlantic, and, just before tucking into an unexpected Christmas dinner, Jason phoned to say: “We are thoroughly enjoying ourselves. Don’t bother booking us in for the rest we planned for when we reach America.”

Five hours later they were back in the pedal boat, cycling through force eight winds and waves of over 40ft high; one of the more turbulent ways to digest Christmas dinner! On January 26, the good ship Moksha pulled into one of the Turks and Caicos Islands just north of Cuba. Approaching the island proved to be on of the most hair-raising parts of the journey so far, as the dramatic changes in water depth around the islands, lead to notoriously choppy seas and exposed parts of the reef. Despite these last minute difficulties, the team made it to the island, stepping ashore into a swarm of school children, given time off school to watch the two “lunatics” arrive. One of the stories they had to tell the children was of the night over the mid-Atlantic ridge, when a whale used the boat as a back-scratcher - “A rather scary experience in the dead of night,” according to Jason.

“It feels like being paroled into a tropical heaven after a long stretch of hard labour and solitary confinement,” relayed Steve over the phone from the Turks and Caicos.

They didn’t hang around for long however; casting back into the ocean eight days later and heading up to Florida. Their estimated time of arrival in the US is mid to late February.

“Then it will be back to square one,” says Kenny. “Except in America we don’t know anyone and we’re illegal.”

Related Articles

Keep On Pedalling - Pedal For The Planet writes back to Squall from where-ever in the world they currently are - Squall 10, Summer 1995

Pedal For The Planet Delayed After Accident - updates from Jason and Steve's crazy adventures - Squall 11, Autumn 1995