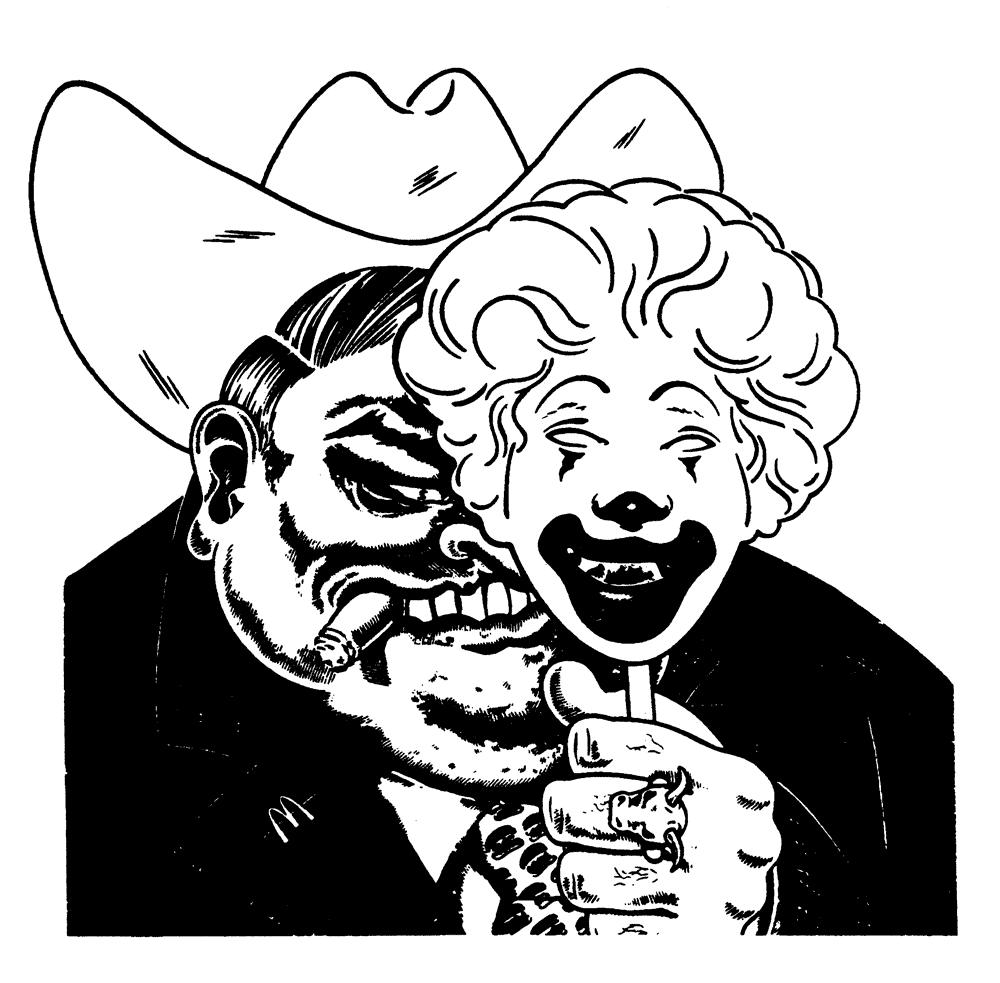

SQUALL McLibel Special: McMammon vs Community

Burger Bulldozing

Public consultation means different things to different people. In a future likely to be economically dominated by trans-national corporations - where does the community stand?

Squall 11, Autumn 1995, p.49

"We take the views of local people in any locality where we are already doing business or where we hope to do business very seriously indeed. That is why we would listen to local residents,” says Mike Love, Director of Communications for McDonald’s UK.

In 1994, Camden Council’s Development Committee rejected a planning application from the McDonald’s Corporation to build a burger outlet in the post office building at King’s Cross in London. The Committee concluded that a 26th burger bar in the area was unnecessary and would “add to environmental problems - to the detriment of the quality of life for residents and workers alike”.

However, in a simultaneous contradiction, the Committee also gave estate managers the go-ahead to alter the post office building in line with McDonald’s intentions, apparently sure that a public outcry and a council planning refusal would not stand in McDonald’s way.

Indeed, by the beginning of this year, the Development Committee had reversed their original decision and given McDonald’s the go-ahead.

“We had a sizeable petition [1,384] signed by local MPs Glenda Jackson and Frank Dobson,” says Harvey Bass, vice-chair of the King’s Cross Neighbourhood Association. “A lot of locals were against it because all that’s coming to King’s Cross at the moment is take-aways and burger bars.”

The local newspaper ran with the headline: “We don’t want a McPost Office!”

However, McDonald’s took a different view.

“We weren’t aware there has been a lot of opposition to the King’s Cross proposal - it went through very smoothly,” says Mike Love, Director of Communications for McDonald’s UK.

Local opposition is, of course, nothing new to the McDonald’s Corporation. Just up the road in Hampstead one of the fiercest local opposition campaigns saw a 5,000 named petition and packed town hall meetings attempt to prevent the Corporation from opening a burger bar on the high street in 1980. The force of local vehemence was enough to stall McDonald’s intentions, but not for long. By 1991, McDonald’s had bought a site on the high street with a pre-existing hot food licence and there was no stopping them.

“At the end of the day, people can do a petition and a campaign, but it’s totally out of your hands, even if you’ve got good reason.”

McDonald’s Mike Love describes the ten year wait to build the burger bar as “ten years of consultation”.

In Camden Council’s second report on the King’s Cross proposal it records how, since their first refusal, McDonald’s had offered to provide “upwards to a hundred full or part-time jobs to locals including school leavers.... all benefiting from continuous company training”. Also recorded is McDonald’s offer to give money to local charities, sports equipment to local youth clubs, coffee mornings for pensioners and the organisation of ‘business days’ for the development of contacts between businessmen and local schools. “Bribes to the community” is how Harvey Bass describes them.

At one stage the Development Committee’s report says: “McDonald’s have been asked if they would include any of the advantages described above, but particularly the local employment policy, as part of the legal agreement. However, they do not wish to do so.”

Despite this however, the Council Committee voted to accept McDonald’s appeal and allow the burger bar to go ahead.

“If there are concerns in an area about a restaurant opening then meetings would be held with residents,” claims Mike Love. “That is a matter of routine in the very few cases where there are local objections.”

According to Harvey Bass, McDonald’s never put their case to either the King’s Cross Neighbourhood Association or the King’s Cross Partnership, a quarterly liaison meeting between local police, residents, councillors and businesses. “They don’t deal with people, they just deal with council officers,” says Bass. “It’s just money, money with them.”

“The local authority is there to exercise planning law and to give permission or not,” says McDonald’s Mike Love. “In doing so they have a legal obligation to consult the local neighbourhood. It’s the responsibility for the local authority to consult. That’s in statute.”

“At the end of the day, people can do a petition and a campaign but it’s totally out of your hands, even if you’ve got a good reason,” says a frustrated Harvey Bass. “The community didn’t want them but to me it’s a simple thing - multi-nationals get what they want in the end, don’t they?”

Meanwhile Mike Love, previously Conservative Party constituency manager for Margaret Thatcher, sees things differently: “We would take every concern, even if it was by one person, very seriously indeed,” he claims.

Related Articles

McMammon Special - series of six articles exploring the McLibel trial and the mighty stance taken by two activists who refused to back down - Squall 11 - Autumn 1995

Still Getting Grilled - anti-McDonald's campaigns across the world are attracting more popular support than ever - Nov-1999

Corporate Cops - Investigation into relationship between McDonalds and the British Police - 2000

A Proper Grilling - The McLibel trial and the legal aftermath reaches its climax at the end of 2004 - 12-Dec-2004

For the full list of Squall articles about the McLibel Trial click here

Links

McSpotlight - the McLibel campaign website - www.mcspotlight.org