Road Wars

Reclaiming The Street Politic

Andy Johnson lets the tape roll on an RTS brainstorm

Squall 11, Autumn 1995, pp. 58-60.

Reclaim the Streets have been out and about over the last few months making a stand and delivering on our crowded and polluted highways.

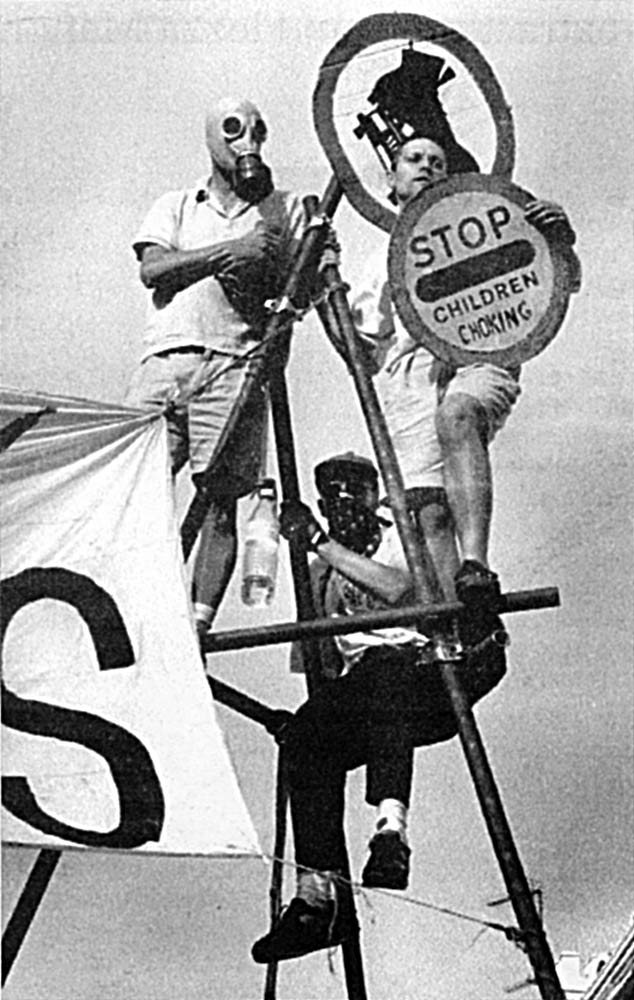

In London, the original Camden debut hold-up was bettered with Street Party Two in Angel, Islington. Scaffold tripods, an idea borrowed from Australian anti-logging campaigns, via Twyford Down, proved a most effective development in roadblocking technology. Children had a sand pit in which to while away the sunshiny day and the grownups were entertained with an armoured personal carrier put to better use as a sound system.

A couple of weeks later RTS sprung an audacious blockage of Greenwich High Street during the morning rush hour; and again at the beginning of September with a morning rush-hour hold-up of Streatham High Road in Brixton.

In the midst of all this, Birmingham RTS held up a main thoroughfare in Mosely and RTS groups have been springing up in Reading, Wales, Blackburn, Oxford, Southampton, Brighton and Nottingham. Just after the Angel and Greenwich actions SQUALL got the beers in and settled down for a long chat with the new knights of the road in London. And a most interesting chat it proved to be:

SAM: After the M11 we were going to open up a squat because at Claremont we’d been protecting buildings. But we felt we had to move the debate on from anti-road to anti-car.

We were originally going to do two actions. The street party in Camden and subvertising.

PHIL: But subvertising didn’t really happen because the street party took up so much time. The idea was to trash as many car ads as possible, put up ads of our own and get the debate into the press.

SAM: We did get some press coverage, there was a phone-in debate on GLR, but press coverage doesn’t affect the decision on actions. What it does do is raise awareness and get the message out.

PHIL: The thing about street parties is the fact that they are so massive, that they involve a couple of thousand people - it’s much more important than actions involving a handful of people. Having a thousand people come from Battlebridge Road (the meeting point before the party, just behind King’s Cross station) to Angel, who didn’t know where they were going, who didn’t know whether or not it was working, and then getting there - to an empty street without cars and a party. Organising that sort of experience is what I’m into. That’s much more important than media success. But media success encourages people to come to the actions.

SAM: Media’s a general kind of advertising.

PHIL: The Greenwich action got more press coverage than the street party. Mainly because it was rush-hour, a weekday, and Greenwich has the worst pollution in London.

IAN: It got the Guardian to do its poll (Which said that most people wanted cars to be restricted in city centres).

SAM: And there was a poll two months ago in the Guardian that said 62 per cent of people agreed with direct action.

PHIL: We had much more press before the street party than after it, which is how you want it because you want people there.

Greenwich was a pollution and smog thing. But the media didn’t pick up on it. They treated it as an RTS protest - blocking streets again. I was concerned how they merged the two things together - Oh, they’re blocking the streets again but doing it during the rush hour. They’re not interested in technique, so in their eyes Greenwich, Camden and Angel were the same thing.

SAM: Greenwich was a solidarity thing. GASP (the local anti-pollution campaign) were there and we were supporting their campaign. Greenwich has the worst smog and pollution in London and the local community were trying to do something about it.

PHIL: After Angel we’d decided to do another action and we were looking for a venue. We decided to do it on the Tuesday and did it on the Friday (August 4). We couldn’t get in touch with every one but lots of people from Greenwich were there and we left it up to them to network. At the beginning I envisaged it as a question of staying there until the police got us down, but they showed no intention of moving us.

SAM: It would have meant getting a cherry picker to get us down. When we said to the police Chill out, it’s only for two hours’ the sense of relief on their faces was visible.

PHIL: One of the differences between Greenwich and the street party was that we wanted the actual party side of it to be a success, so we put a lot of thought into how traffic could be redirected. At Greenwich the idea was to try and block the traffic. To make it wait. One was creating a car-free space, the other was about blocking cars. We reckon street parties are the answer to the CJA. Street parties are in a public place where it’s much more dangerous for the police to go in. And the media are there so the police can’t get out of hand.

SAM: And the location is kept secret. It’s the same skills as putting a party on indoors, with one or two exceptions. The Mother Festival, for example, had the location on the phone lines 15 hours before it was due to start.

PHIL: It’s also easier to go from tube stations where the police can’t use their radios, so they can’t do anything until there’s so many people there they risk a public order problem.

SAM: Country lanes are easier to block, and at street parties the police can’t tell the difference between activists and ordinary folk. The idea of the CJA is to criminalise communities, so that they can’t have space. Street parties are about reclaiming space - to do what you want to do. It’s resurrecting space for people.

PHIL: If you think what streets have been since the beginning of cities - right back to ancient Greece - they have been places where crowds gather, people meet and exchange ideas. The grass-roots of democracy takes place in public spaces on streets. The car undermines that democracy because it dissolves the space. A lot of anti CJA activity has been about creating mini public spaces.

SAM: Roads are now used for cars and there is no public space. There are no spaces that aren’t owned by people and everything that goes with that - fear, paranoia and neighbourhood watch schemes. There is no forum for debate. You can’t talk to people or meet people because of roads and congestion. The car is a metaphor for all these things. We’re using the car to illustrate other things - urban planning, space, cars for profit: Capitalism. It’s really amazing how quickly people understand these issues.

PHIL: Pollution as well. Everyone is aware of the environmental impact of cars. But what they can’t do is talk about space. So as the campaign develops we get more into these issues. Before it was the environmental impact now it’s the social impact. Cars are not a solution that would ever have been chosen collectively by a society. By their very nature they always represent a purely individual solution. The sum of everybody’s individual ideas is complete chaos. But they’re not intrinsically wrong. Technology isn’t intrinsically wrong.

IAN: And that obsession with uninventing the technology is the mirror image of the technological fix of making cars greener. It takes the argument away from the issue that cars are really bad socially.

SAM: Cars create a need for themselves, such as out of town shopping centres and long journeys which are too expensive on the train. In cities, on an individual basis, individuals need a car. The reason they do is because everything is so far away. In a rural area it’s not intrinsically bad because everything is far away anyway and not developed around the car.

PHIL: But even in the countryside there are other forms of transport. Cars dissolve the city, in the countryside they may be spread over a wider area but they still have a lot of disadvantages.

SAM: Transport reflects life. Slow it down, so that it’s not as important to travel and always be in a hurry. This society is based on moving people around as quickly as possible.

IAN: In an organic way it’s like saying driving is morally bad. There’s no point thinking it’s going to disappear overnight. But can we come away from it? It’s not a case of goodness or badness, but of shifting the social parameters. Keeping it in the realms of social change that is necessary for a decent public transport system.

PHIL: Car emissions have got to be quelled and that’s a massive reason why cars are bad.

IAN: The way our message has come across is that we hate cars. It’s a simple and easy message to get across. But the whole problem is that the issue gets taken up in a negative way. That individuals have to give up cars and make sacrifices, rather than being seen as a social problem that has to be addressed in a coherent, social, way - through transport policy and urban planning.

PHIL: The problem is what we might want and how we are going to realistically achieve that. On the one hand we talk about public space, eradication of the car, the car as a metaphor of consumer, capitalist, private lifestyle that has to go. But the question is, what effect will we have? At the moment the anti-car message is getting across really well, the World in Action programme (on RTS) presented it really well. Cars, like fur coats and cigarettes, are going out of fashion. People aren’t into them anymore. But the problem with that is that it’s easy for the government to use the anti-car message and do a greenwash by doubling the price of petrol so cars can’t be used by poor people but putting nothing into public transport.

SAM: Which were not into. In the short term we’re arguing for more public transport. But in the long term we’re questioning the reason for transport anyway. We have to have viable alternatives, because the major argument now is that there are no viable alternatives.

PHIL: You have to recognise the ways you are likely to be misunderstood and misinterpreted. It’s a question with public transport in particular. Unless it’s actively struggled for it may not happen.

SAM: Direct action is an end in itself and also more a means to an end. It’s doing something here and now with something you’re not working to achieve here and now.

PHIL: People’s sense of powerlessness is overwhelming. People feel in general their ability to influence anything has been taken away from them.

IAN: It’s the last resort.

SAM: It’s the first resort. You don’t have to be clued up to put actions on.

PHIL: We were surprised by how easy it was. Blocking the road part was easy.

IAN: It was inevitable that it (Angel) went so well.

SAM: We were more worried about Camden because we hadn’t done anything before. We knew there would be a lot of people there, but we couldn’t predict the police reaction. So it was a good test. If you have enough people, such as at Camden, the police can’t tell the difference between activists and everyone else, so they’re more concerned about numbers. We knew from Camden that it was possible to do a party. It’s experience. Every time you do it you push the boundaries further.

PHIL: What were also doing is putting together an information pack. Ideas for actions, how to do a street party, dealing with the media, setting up an office. So that there will be lots of autonomous groups. It’s not the way to do it for people to rely on London.

For information see CONTACTS page 87.

Related Articles

Reclaiming The Air - Report from the first Reclaim The Streets, Camden High St, London, May 14th 1995 - Squall 10 - Summer 1995

For a menu of many other Squall articles about the Anti-Roads Movement, including protest camps, Reclaim The Streets and more click here

Links

Reclaim The Streets - http://rts.gn.apc.org