Road Wars

Reclaiming The Air

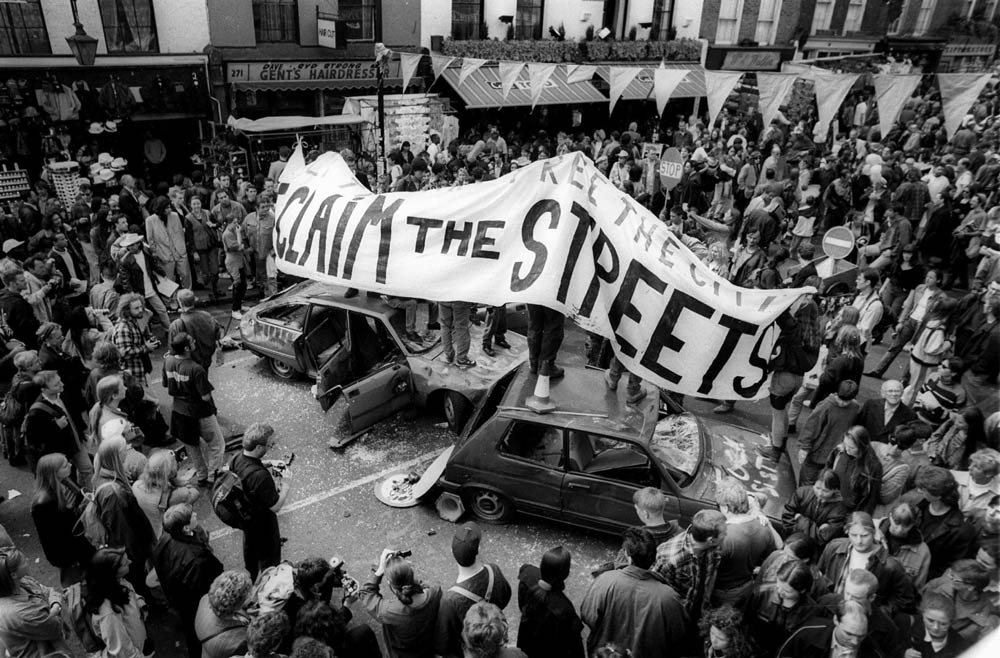

The first Reclaim The Street event, Camden High Street

Concern over the effect of pollution on the health of the nation has spawned widespread environmental direct action. Andy Johnson talks to some of the hundreds of people who recently reclaimed the airwaves on a North London street.

Squall 10, Summer 1995, pp.20-21

A child jumping up and down on the roof of a recently trashed car shouting “Kill the car, not us,” embodies many symbolic connotations. Not least the reversal of a deadly relationship between the two.

Further appropriate symbols come tumbling from a bicycle-powered sound system, Rinky Dink, delivered succession after succession of repetitive beats in the same busy London street as the child and trashed car. And more yet in the swarm of illegally gathered dancers attracted to it.

Throw in a few jugglers, fire breathers, ad-hoc drumming jams, folk bands, bunting, a free cafe, 400 environmentalists and thousands of market day visitors and you have a spontaneous street party.

Or, in the words of Roger Geffen, one of the many inspirations behind Reclaim the Streets: “the possibility of what can be done when you reclaim the streets and give them back to the people.”

On Sunday May 14th Camden High Street in North London was reclaimed for an afternoon. It was the first action by Reclaim the Streets - an evolution of anti-roads campaigns such as the No M11 and No M65.

Their choice of target was inspired. Camden High Street is a main northern artery through London, designated a priority “red” route by the Department of Transport.

But on Sundays it is packed with thousands of market visitors as car and pedestrians habitually jostle for road space.

The organisers behind the action knew that as soon as they managed to halt the traffic, market shoppers would flood the road - leaving the police with no alternative but to close it.

The action had been planned since February. Two sacrificial cars, brought specially for the occasion, had been parked overnight in a nearby side street.

While 400 demonstrators left from a meeting point in nearby Kentish Town, 20 activists preceded them. They drove the cars into the High Street and smashed them into each other - blocking the road.

Most of the demonstrators did not know where they were headed. Although the action was well-publicised, the location had been kept successfully secret.

“We knew that a demonstration was planned for somewhere in London,” said Superintendent John Gillespie of Kentish Town police, “but we didn't know where until they arrived.”

“Roughly translated,” said one police officer, “we got caught with our pants down”.

After demonstrating to London Underground that penalty fares do not deter fare-dodgers, the main body of protesters arrived minutes after the blockade of the High Street.

“We jumped out of the cars and put up bunting and tables very quickly,” said Sheila, one of the core initiators. “There was nothing the police could do. The minute it happened everybody else showed up. And then people simply filled up the car-free space provided.”

The police quickly realised there was nothing they could do. They siphoned the trapped traffic off the High Street and then closed it.

Many key members of Reclaim the Streets are fresh from anti-road protests. They take their inspiration from the effective non-violent direct action of this movement but now intend to crank the transport debate up a notch.

“It’s in line with trying to get traffic out of cities,” says Shiela, “because they’re for people and not traffic. To curb car culture and show what life would be like without cars.”

Roger Geffen expands: “The car is implemented in many different crimes. Pollution, asthma, global warming and the danger they pose to everybody else. Cars are congesting our towns and cities. Our houses are being knocked down to make way for more roads. It’s no longer a question of whether we are prepared to make the sacrifice, but that life would be better without them.”

The issues are serious. The Reclaim the Streets action came on the same day many similar actions around the globe took place in response to World Climate Action Day.

A report published in the New Scientist (12.03.94) suggested that fine particles in exhaust fumes could be responsible for 10,000 deaths a year in England and Wales.

And, although environmental and health organisations are wary of saying pollution causes asthma, there is strong evidence that it worsens the condition for asthma sufferers. Especially during hot weather.

Last summer, according to Camden council, vehicle exhaust fumes frequently caused air quality to breach European guidelines in the area.

According to the National Asthma Campaign, asthma is the only easily treatable chronic condition in the Western world that is on the increase. Israeli researchers have discovered that there are more asthma sufferers in industrialised regions while researchers in Munich have discovered a “definite association between reduced respiratory function and increased traffic load”. (British Medical Journal '93: 307).

“When pollution levels are higher,” says Tony Bosworth, transport and pollution campaigner with Friends of the Earth, “more people visit doctors for asthma, more asthma medication is sold and more asthma sufferers are treated in hospital.”

Ozone is something we need more of a few miles up in the atmosphere to deal with the sun’s UV rays, but at low level it causes chest tightness and breathing difficulties. It also destroys vegetation.

According to the DoE and Friends of the Earth, low-level ozone is more prevalent in rural areas. Low-level ozone drifts, from its source, out to the cooler and less congested countryside.

The most deadly pollutant, however, are fine sooty particles called particulates that come mostly from burning fuel. Diesels, in particular, produce high levels of particulates. An American scientist, Joel Schwartz, who works for the US government’s Environmental Protection Agency, estimates that 60,000 people a year in America die as a direct result of particulates. Most vulnerable are the elderly, followed by those with heart or lung, disease.

From these results Schwartz calculated that deaths in England and Wales attributable to particulates run at about 10,000 a year. Two thousand of these would be in London.

But, as Tony Bosworth points out, we don’t breathe in these chemicals separately. “When we’re out walking or cycling we breathe in a nasty cocktail of all of them,” he says.

According to Friends of the Earth, catalytic converters are not the solution. While they are effective at reducing the flow of poisons from exhaust fumes, the sheer expansion in car ownership projected for the next 30 years will cancel out their effect. There are currently 25 million cars on Britain’s roads. According to the DoTs own figures, by 2025 this number is expected to double.

“If they are allowed to,” says Tony, “the benefits of catalytic converters will be wiped out.”

This view is not just held by environmentalists. The Royal Commission on Pollution, the House of Commons Environment Committee and the House of Commons Traffic Committee have all recently come to the same conclusion.

“What we have to do,” says Tony, “is get people out of their cars. Not just through a political framework but by putting out a different message. The propaganda put out about the car does affect people’s behaviour. But people can’t make a choice unless there is a decent, reliable alternative.”

In Camden the two sacrificial cars had been well and truly sacrificed. A budding new-age entrepreneur could have hired out large sticks at 50p a minute and made a tidy profit, such was the fervent desire of passers by to vent their resentment against the car.

As children jumped on their roofs, and firemen poured sand down their petrol tanks to prevent a final act of defiance, Camden High Street was awash with bobbing heads. There was almost a festival atmosphere - a sort of aperitif for the summer.

Camden High Street is intersected by a junction of five major roads. From the relative vantage point of a small bridge that crosses the Regent’s Canal this junction could be seen to be gridlocked. The sun, glinting from the windscreens, trembled in the gaseous haze produced. A shimmering sea of filth.

“Brian Mawhinney, the transport secretary, says that if you ask the individual if they want to do without the car they say no,” says Roger Geffen. “The transport debate is cynical. He is asking the wrong question to get the wrong answer. If he asked collectively if we want to get rid of the car, we’d all say yes.”

A survey of the traffic jammed motorists bears out this view. Most drivers interviewed were annoyed at the immediate inconvenience. But there was agreement that something had to be done about the city’s traffic problems.

Even a taxi driver, always good for a reactionary view, said: “I think there’s too much traffic. They should take all the cars off the road and provide a proper bus service. And they should cut taxi fares in half so that people can afford to use them. People should be able to walk without breathing all these fumes in.”

The day was a peaceful one. Superintendent John Gillespi described it as “quite humorous”, although it is known that the local police were annoyed at the action.

During the day there were no arrests. But at the end of the demo - scheduled for 5.30pm but extended by a couple of hours - 10 people who refused to move when the road was re-opened were arrested on obstruction and public order charges. Most were later released with cautions.

Road protesters are not alone in targeting this new, invisible and deadly smog. Recently the Government said that local authority powers to close roads under the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 can include health considerations.

Camden Green party are making noises to the effect that traffic through Camden should be halted during hot weather. Meanwhile, parents of children with asthma are going to the High Court to force Greenwich Council to close its main through-road at times of high pollution.

A week after Reclaim the Streets, 100 parents and children spent the morning rush hour leafleting drivers on the dangers of pollution at a major junction in Islington, north London.

“It is women and children who have to breathe these fumes in,” said Joss James, one of the organisers. “This is the first action,” says Roger Geffen. “We want this to become the permanent state of things. We shall be taking the campaign to all aspects of car culture - including advertisers, manufacturers and the streets. We have moved the debate on from anti-road to anti-car.”

Related Articles

For a menu of many other Squall articles about the Anti-Roads Movement, including protest camps, Reclaim The Streets and more click here

Recommended Viewing

Reclaim The Streets, Camden, 1995 - a short film about the day available on YouTube Click here

Links

Reclaim The Streets - https://rts.gn.apc.org (as of 2024)