Going Round In Circulars

The increasing eviction of traveller sites is being facilitated by the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act in ways contravening government directives. Jim Carey reports on the hounding and the lipservice, and also at travellers’ attempts to create planning law precedents.

Squall 10, Summer 1995, pp. 29-31.

“Every eviction is caused by the knock on effect of an eviction somewhere else,” observes Steve Staines, a coordinator of the campaign group Friends and Families of Travellers. “Travellers move to a place that they think is safe and then that site gets bigger, so it gets evicted. The whole cycle goes on and its a cycle of nonsense.”

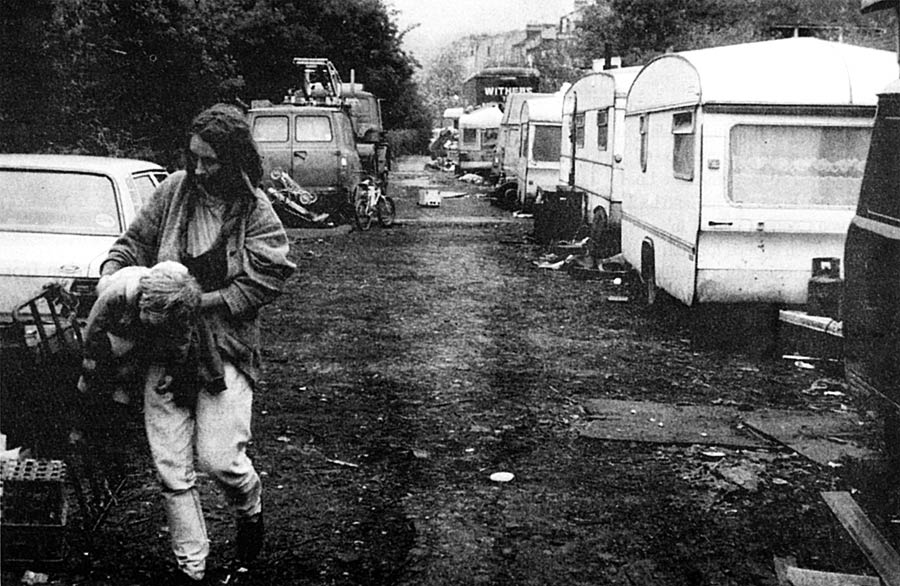

It is certainly an unsustainable situation for many travellers, particularly those with children, who grow tired and angry at never being able to park up for more than a few weeks before being hoisted needlessly from their resting place. It is one of the reasons why organisations such as Save the Children and the Children’s Society fought so vehemently against further eviction measures contained within the Criminal Justice Act.

By way of placating concerns voiced by such social rights organisations, certain government departments have issued a number of circulars directing local authorities to give consideration to the needs of travellers.

In one DoE circular (18/94), it says: “In particular, where Gypsies are camped unlawfully on council land, are not causing great nuisance, and have no alternative authorised accommodation to go to, authorities should consider tolerating their presence on the land temporarily”.

It goes on: “It will continue to be the policy of the Secretaries of State that Government Departments should act in conformity with the advice that gypsies should not be moved unnecessarily from unauthorised encampments when they are causing no nuisance and have no authorised site to go to.”

So there are the words - but where is the reality?

The eviction of the Beechen Cliff travellers’ site near Bath at the end of last year, provided one of the most striking examples so far of the dirth of substance behind these circular recommendations.

The Beechen Cliff travellers site was situated at the disused and rapidly deteriorating Beechen Cliff Lower School on Wells Road in Bath. The City Council, as befits the predominantly right wing politics of Bath, had sought an enforcement notice against the travellers, despite the fact that Avon County Council were in favour of applying for planning permission to establish the site. Avon consequently appealed against Bath’s decision to evict the site, resulting in the matter being referred to the Department of Environment.

In DoE circular 1/94, it says: “Vacant land or surplus local authority land may be appropriate (for the provision of sites)”.

The DoE sent an inspector, Mr RJ Tamplin, who spent many months interviewing neighbours, local authorities and the travellers themselves, before writing his report and making recommendations about appropriate courses of action. In his report, Tamplin acknowledges that the number of travellers at both Beechen Cliff and at nearby Rainbow Woods, “reinforces the evidence that there is currently an urgent need for provision in Bath”.

Indeed DoE circular 1/94 says; “In deciding what level of provision is necessary, it is essential for authorities to have up-to-date information and to maintain records of trends in their areas.”

Tamplin also acknowledged the site to be barely visible from public vantage points, with complete visual anonymity achievable via “a judicious screen fencing, which itself need not harm the appearance of the area.”

Ironically, despite Bath’s protestations that the travellers were ruining the site, Tamplin points out that the more important visual effect of the site comes from the “derelict and ugly condition” of the disused school; damaged by fire, partial dereliction and vandalism predating the arrival of the travellers. As such it remained an eyesore because the local authority had failed to do anything with the empty building.

The inspector’s report goes on to say: “During the inquiry and my site visit it became apparent that local residents accepted that some of those occupying the site were worthy of certain respect. This is born out by the petition and letters of support and reinforces the argument that those on site are generally a reflection of the population at large, albeit with a preponderance of the younger and probably less conventional part of the community.”

Having concluded his enquiries, Tamplin recommended that the site should be allowed to exist for three years, with any overcrowding problems limited by a restriction of site pitches to nine caravans or trucks. In the eventuality that the Secretary of State for the Environment would chose to disagree with this recommendation, Tamplin suggested that the travellers currently living on the site should be given at least nine months to move on and not the 12 weeks that Bath City Council were attempting to enforce. His reasons for recommending this alternative were written in the final paragraph of his report: “I consider that the presence of the several children on site who attend local schools/playgroups merits sympathetic consideration. So to does the fact that the site is the only home for many of the occupiers.”

Indeed, in another DoE circular (18/94), it says: “Authorities should also bear in mind their statutory duty to make appropriate educational provision available for all school-age children in their area, whether resident temporarily or permanently. This duty embraces in particular traveller children, as noted in para. 5 of Circular 1/81 and para 9 of Circular 11/92 from the Department of Education and para 6 of the annex to Welsh Office Circular 52/90. Authorities should take particularly careful account of the effects of an eviction on the education of children already enrolled at a school.”

Tamplin then submitted his completed investigation with his recommendations, for the Secretary of State, John Gummer, to consider. And the result?… Gummer overruled both of Tamplin’s recommendations and gave Bath City Council the right to evict the travellers within 12 weeks.

“They came and served notice on us one week before Christmas,” recalls Mike, one of the travellers on the site. Mike lived at Beechen Cliff with his partner Coral and their two children Sunshine (aged 5) and Tara (aged 13). They have since moved their bus to London.

“Tara was happy in Bath,” says Coral. “For the first time in her life she could start school on the first day of term with everyone else. It’s been really hard on her.”

Despite farcical situations like the Beechen Cliff enquiry, travellers and the groups campaigning on their behalf, continue to explore the possibilities of planning permission for temporary and permanent sites, as a respite form constant eviction.

But the fight is a long one. In April of this year, the DoE overruled Avon County Council’s attempt to establish planning permission for a site at Racecourse Quarry in Woodspring.

Three years previously, a number of Travellers moved onto the quarry site; leased by Avon County Council from the landowner Lord Wraxall, as a gravel storing area. As the Council were not using the site, they allowed the travellers to stay there. Lord Wraxall, on the other hand, wasn’t happy about this at all.

Educated at Eton and Sandhurst Officers’ College, Lord Wraxall happens to be chairman of the North Somerset Yeomanry Association and President of Woodspring Conservative Association. Small wonder then that Wraxall was appalled at the prospect of travellers staying on land that he owned. Woodspring District Council (due to become North West Somerset Unitary Authority next year) are notoriously anti-traveller, a recipe for many a Tory hernia bearing in mind the area is a passing place for travellers moving between Avon and Wales. Not surprisingly, Woodspring District Council served a planning stop notice on the travellers, potentially leading to heavy fines for the contravention of planning laws. At the same time Lord Wraxall tried to wrestle his land back from Avon County Council. In response, Avon applied for both planning permission for a travellers site on the land and a compulsory purchase order allowing them to acquire the property at market value from Wraxall. Meanwhile Avon temporarily rehoused the travellers on a site at Willamead, an ex-mobile home tourist site originally bought by Avon for a road building scheme. The existence of a mobile home site licence meant that the travellers could stay there for three years. Once again there were children and pregnant travellers on site.

Meanwhile the DoE sent an inspector down to jointly consider both Avon County Council’s compulsory purchase order against Wraxall and the application for planning permission on the Racecourse Quarry site.

A major factor in the enquiry was the pressure put on the inspector by Liam Fox (Con MP - Woodspring).

Fox is a Parliamentary Private Secretary to none other than Michael Howard and testified against the travellers during the course of the enquiry. After a three year enquiry the inspector overruled both applications and the land was handed back to Wraxall.

Battling with the landed gentry is of course nothing new, but it is worth noting the current forms in which these battles are fought. Another case in point involves the Semly site in Wiltshire, which became the object of Lord Talbot of Malahyde’s prejudiced attentions in April this year.

The Semly site has existed for at least four years, and perhaps as much as eight. It is surrounded by woods; with the nearest neighbour over half a mile away, and the next nearest a full mile away. Recent evictions of other sites in the surrounding counties had forced travellers, including once again pregnant mothers and children, to seek sanctuary at the relatively safe Semly site. Some of the travellers at Semly had not been in one place for more than a month in the last two years due to constant eviction.

Lord Talbot of Malahyde is what is known as an Irish peer and is therefore not entitled to sit in the House of Lords. Never the less he does sit in Wardour Castle fuming about the existence of travellers in his area.

“A better site you couldn’t think of in terms of nuisance to neighbours,” comments Steve Staines from Friends and Families of Travellers. “But along comes Lord Talbot with flanking police officers and tells everybody to leave his land.”

The following day the police turned up with Section 61 notices (CJA police powers to order unauthorised campers to move when there are 6 vehicles or more) and the forty vehicles on site were given three and a half hours notice to move. In a Home Office letter sent to police forces and local authorities around the country, advising them on the provisions in the Criminal Justice Act, it says: “During the passage of the bill through parliament, the Government undertook to draw the following point to attention in relation to this provision when a circular was issued. The decision whether or not to issue a direction to leave is an operational one for the police alone to take in the light of all the circumstances of the particular case. But, in making his decision, the senior officer at the scene may wish to take account of the personal circumstances of the trespassers; for example, in the presence of elderly persons, invalids, pregnant women, children and other persons whose well-being may be jeopardised by a precipitate move.”

There were indeed several children on the site and one pregnant traveller called Jenny was forced to drive her heavy vehicle off-site whilst in the seventh month of pregnancy. She had no-where to go. Despite protestations from both Friends and Families of Travellers and the Children’s Society the chief superintendent at the scene was adamant there would be no negotiation.

According to local sources, the pressure on the police to act in this case had come from “three floors up” and it now looks likely that Lord Talbot of Malahyde was doing some of the whispering. Although the owner of the Wardour Estate, his ownership of the stretch of land upon which the Semly site was situated is in some doubt. At the same time as the police served a section 61 CJA notice on the travellers, Lord Talbot also took out an order 113 civil county court action. In the accompanying affidavit, the land ascribed to the ownership of Lord Talbot was in a different place to where the travellers site was. If it had been necessary to attend the court case in Salisbury, Lord Talbot would have lost on this point alone.

Despite the fact that Lord Talbot told the travellers and other observers to remove themselves because it was his land, a Wiltshire County Council memo makes reference to his interest in the land as being in his capacity as chairman of the Commons Committee for the area. However, the police do have powers under section 61 of the Criminal Justice Act to direct travellers to leave if there are more than six vehicles, although this is discretionary on the senior police officer, particularly when there are pregnant women and children on site.

Up until April of this year, the Semly site had been tolerated as a resting place for travellers as it was not causing a nuisance to the locality. However, a few words coming from the castle so it seems, renders such toleration and government department recommendations, instantly dismissible.

There is still strong hope that planning permission can be obtained for certain sites, particularly where travellers are trying to settle on their own land. Indeed, a few precedents might spark off opportunities for many.

As a consequence, planning permission for ‘low impact dwellings’ is being vehemently sought by many travellers and small subsistence settlers, in order to set just such precedents and find respite from continual harassment.

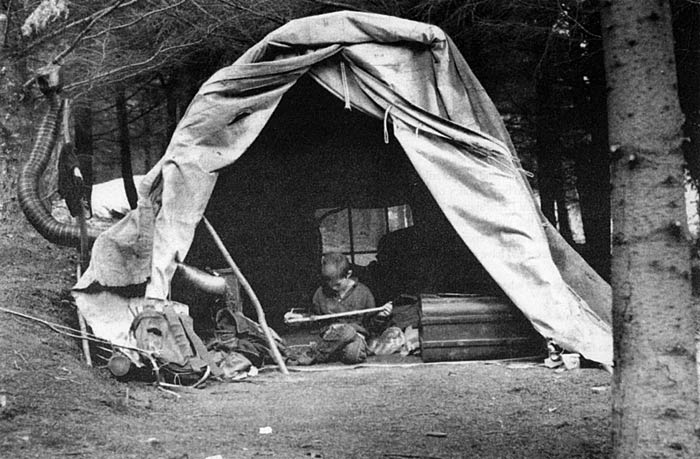

One opportunity for establishing an important precedent is in the application made by the bender dwellers at Tinkers Bubble in Somerset. The residents of this wooded area near the village of Norton Sub Hamden, own the land themselves and have made a planning application to live there and tend the small subsistence agriculture they have established on the site. Due to the current agriculture and residency criterion of ‘economic significance’, their thousand apple trees and small number of animals, does not qualify even one person to live on the land under existing planning law. The residents of Tinkers Bubble have applied for twelve.

The DoE once again sent an inspector to conduct a two day public enquiry into the situation in the local village hall.

“It went extremely well,” says Chris Black, one of the residents at the Bubble. “We put up a good case and a lot of the local objections fell away.”

Their first application for planning permission had been narrowly defeated by seven votes to six. “Quite a few locals did stand up and object - it’s got a lot to do with the house prices,” observes Chris.

However, their current appeal against that decision is backed up by a well researched and composed proposal drawn up by Simon Fairlie, until recently a co-editor of The Ecologist magazine and now full time resident of Tinkers Bubble.

The plan involves a certain amount of agricultural work to be done and costed against what people are getting on the dole. The proposal suggests that people who want to work their own land should be able to do so, with £2,500 as the minimum agricultural income necessary. At the moment, anyone who wants to show an agricultural need to live on the land, has to show a vast turnover, unfeasible without chemical fertilisers and machinery. The residents have indeed lived on the site for a couple of years, despite not having secured planning permission; a situation that has allowed the locality rise above their initial adverse reaction by experiencing the reality behind the stereotype.

When they first arrived, local parents threatened to remove their children from the village school unless the headmaster got rid of the Tinkers Bubble children, who had also started attending. The headmaster to his credit stood his ground and refused. The objecting parents recanted and left their children in the school. The same thing happened with the local shopkeeper, threatened with loss of custom unless he refused to serve the travellers living on the Bubble. Once again, he refused to comply with their threats. One traveller, called Fraggle, who doesn’t live at the Bubble, but who came to visit a resident who was about to have a baby, had her bus burnt out by local vigilantes. However, things have changed in Norton Sub Hamden since the initial hysteria.

“There’s been an enormous change in attitude in most of the local people - they’ve decided that we’re not so bad after all,” says Chris thankfully. “A lot of them have come up and had the odd cup of tea and are friendly. To begin with, there were all these wild stories that we were the spearhead for hundreds of other people that were going to come and live in the woods. But we’ve shown that we’re relatively serious about keeping it to a small number of people and living with our subsistence agriculture.”

The decision on whether to allow Tinkers Bubble planning permission or not, has been called in by Environment Secretary, John Gummer, for his personal attention. All eyes are now on Gummer to show signs that the circulars published by his department do not remain insubstantial rhetoric.

“We’ve got a fairly good chance and we’re fairly optimistic,” says Chris Black. “If we don’t win this time, we’ll win eventually. Gummer would be sensible to cut a long story short and give us the permission, but we have no intention of giving up and going away anyway.”

(There is to be a Channel Four programme exclusively about Tinkers Bubble to be shown on July 10th at 8pm)

Planning permission is a highly subjective process and very prone to discriminatory prejudice. Friends and Families of Travellers recently conducted an analysis of planning applications in south-west Britain. They found that whilst 90 per cent of travellers’ planning applications failed, 80 per cent of planning applications made by settled people succeeded.

The original consultation paper, setting out the measures made manifest in the Criminal Justice Act to curb Britain’s nomads, said that travellers “should be encouraged to move into settled accommodation”.

This begs three questions. What encouragement? Why do travellers have to settle? and Where are they to settle?

The answer seems that there’s little encouragement beyond the words, and so, in true DIY style and without waiting for more words, travellers are attempting to find peace from harassment through establishing bender sites and subsistence agriculture; thereby remaining free from the bed and concrete breakfast nightmare. Sustainable and fulfilling - the right to live on your own land.

Up until now the Government haven’t allowed this either. It remains to be seen whether anything substantial can be teased from the placatory rhetoric contained within government circulars.

Related Articles

Where Now? - Rachel Kano talks to fellow Travellers about surviving the CJA - Squall 14, Autumn 1996

Travelling Under Pressure - manoeuvres to erode the travelling community in an ethnic whitewash - Squall 10, Summer 1995

Travellers Abroad - indications that travellers are leaving Britain to avoid prosecution under CJA - Squall 9, Jan/Fen 1995

Click here for a list of articles by SQUALL about the Criminal Justice Act and Public Order Act 1994 covering: the build-up, the resistance, the counter-culture, the consequences, plus commentary of its process through Parliament.