Fashion Victims

Clothes to die for? That’s exactly what some companies are making. Susie Fenn examines the work of the Campaign for Labour Rights and finds out why Nike gets no points for style.

Squall 16, Summer 1998, pg. 17.

Nike - the super stylish, oh so concerned about public image, sports company is being sued by the State of California. A press release issued by the progressive news agency Communications Works stated: “Nike has illegally misled and deceived Californian consumers about working conditions and wages in its overseas factories.”

Nike spends an average of 90p on labour to make a pair of trainers and between 5-600 million dollars a year on athlete endorsement and advertising.

The Campaign for Labour Rights feels that this lawsuit could be tremendously important in pressurising Nike to under-take a systematic reform of their labour practises.

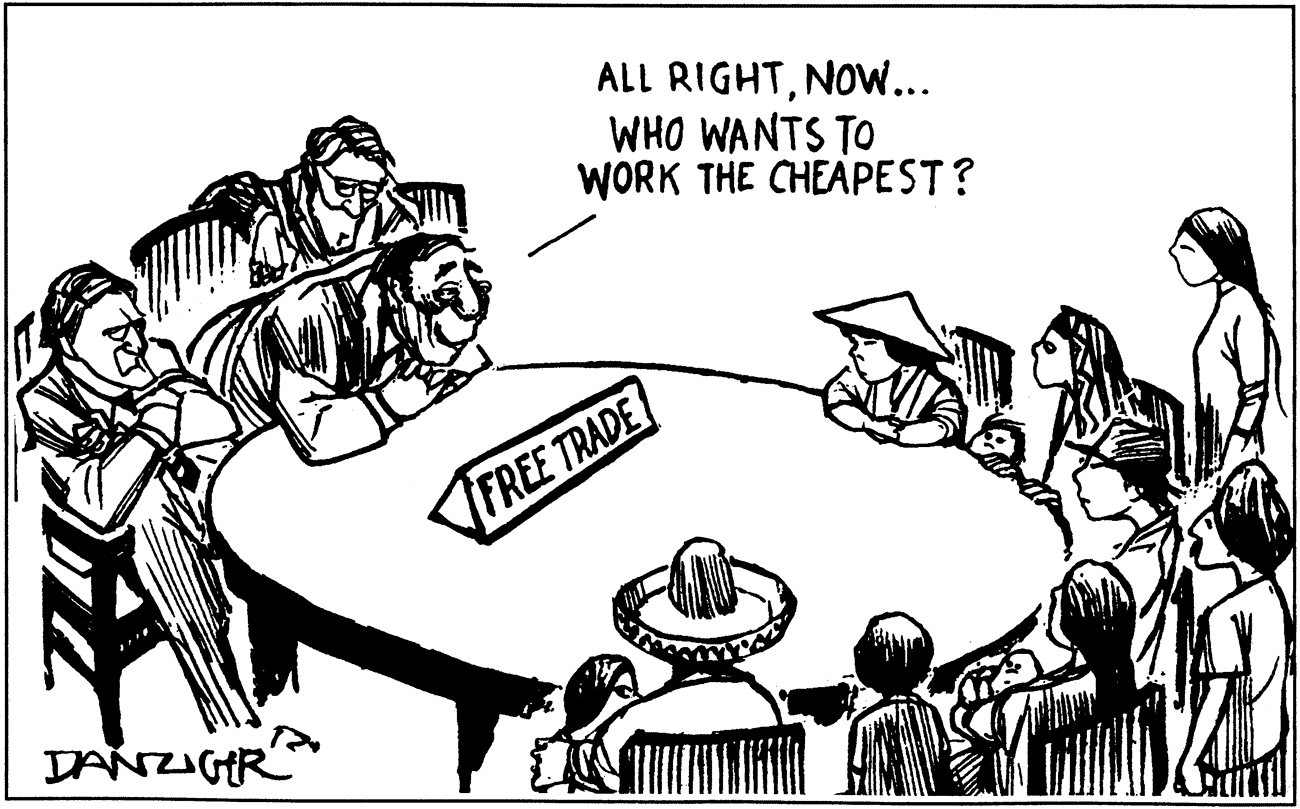

As a leading, globally influential company Nike has been the focus of many campaigns on exploitation in the clothing industry, they are by no means the only offender but rather the more high profile tip of the iceberg. They have constantly been accused of using slave labour in Asian countries with severely oppressive regimes such as Vietnam, Indonesia and China, countries not known for their democracy but more for their human rights offences. Like many other companies trying to keep their costs down they scour the world looking for the cheapest (company speak: ‘efficient’) labour. A common tactic employed is playing countries off against each other. David Moberg, a senior editor for In These Times magazine, reported overhearing a Nike representative in a factory discussion on wage levels saying: “Maybe Indonesia is pricing itself out of the market.”

Moberg’s article, published in the LA Times last year, is an account of a visit to several Nike factories in Indonesia including Nike Town which, he says, “is the largest factory in the world making shoes exclusively for Nike.... The factory provides housing for 12,000 workers. Nike town seems to have gotten rid of the physical sweatshop, while leaving the particulars of sweatshop labour; low wages, increasing work intensity and discipline, without meaningful worker representation entirely in place.”

He talked with a group of women in the dormitories, where he says “twelve workers inhabit a room barely large enough to contain six double bunk beds, jammed side by side.” Female workers, although happy to have a job, complained about the pressure: “Almost every day, if we make a mistake, or don’t make our quota, we’re called horrible words: you’re dumb, you’re stupid.... If we don’t achieve our target today, the supervisor makes us do it tomorrow, and we don’t get paid over-time,” a 24 year old Javan woman told him. They work through lunch and have overly long days. “Pay is so low, many cannot keep up rent payments or afford more than one modest meal a day to supplement the food their employer is obliged to provide.” Another worker told him: “It’s work; go home, sleep, eat, go to factory, work. Sometimes I dream of a weekend holiday, but it’s only a dream.”

The Campaign for Labour Rights, who have been closely following Nike’s business and labour practices, report that,“Michael Shellenberger, of Communications Works, emphasised that this (law)suit is not about the money, but about getting Nike to correct the discrepancy between its public rhetoric and its actual labor practises overseas”. They say Shellenberger agreed with the assessment that “The object is not to have Nike bring its claims down to the level of its practises, but to force the company to bring its practises up to the level of its claims.”

The campaign group further claim:“This is the first time the shoe giant has faced legal action over its labor policies. The lawsuit contends that Nike’s advertising and public statements present a deceptive image of the company, and that Nike falsely claimed to protect workers through a Code of Conduct and Memorandum of Understanding.” Campaigners have been demanding that codes of conduct must be independently monitored. The Campaign for Labour Rights insists that reports from local NGOs, human rights groups and religious organisations are used to verify information.

Their report continues: “The most damning evidence is contained a 1997 Ernst and Young internal audit” by a disgruntled employee to the New York Times: “Their inspection of a Vietnamese shoe plant found evidence of widespread health and safety violations. These included exposure to workers of reproductive toxins, like toluene, at 177 times the legal limit.”

Research by Oxfam & Christian Aid have found these export processing zones (areas where foreign companies are offered tax breaks and exemptions from labour laws if they invest) have an 80 to 90 per cent female workforce aged between 16 and 24 years, by which time they are too unhealthy and exhausted to work. An International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) report states that they are subjected to a level of abuse, exploitation and humiliation which would cause a public scandal if it happened in the investor’s own country. Often the women are migrant workers with little control over their lives, commonly forced from their homeland due to the expanding global economy [their land being used by transnational companies, taken by the government or wealthy land owners]. They are often working at a level that often just about keeps them from starvation.

In Rosario, the Philipines, on March8th, Carmelita Alonzo, a sewing machine operator at VT Fashion Inc, died of excessive work, her co-workers stated. March 8th was, ironically, International Womens Day. Workers denounced the system of quotas set by the company which forced them to work 12 to 14 hours a day plus seven hours overtime on a Sunday. This particular factory has produced garments for many US-based companies including The Gap and Benneton. Other reports from the Philipines, the Dominican Republic and other free trade zones say that the lack of bathroom facilities and strict discipline often leads to health problems such as urinary tract infections. The ICFTU states:“In some countries, young women have to take a pregnancy test before they can be hired. If they later become pregnant, they are sacked.”

Workers usually have no union and are in fact banned from organising themselves. Usually they have no rights and will be dismissed if they complain of the conditions or are even heard talking about them. They are trapped. In repressive regimes, to fight for your health, your children or basic rights is seen as subversion, and a threat to national security. The local military are often used to control dissent and expressions of dissatisfaction. The freedom to associate and collective bargaining is a vital right for workers to be able to strike in this environment.

“The level of frustration must have become unendurable,” reports labour alerts for the Campaign for Labour Rights.“Any union activity in Indonesia [for example] takes place in a context of severe repression.”

In Indonesia, at least 330 peaceful activists had been arrested by the middle of March. Amnesty reported, in November ’96, the arrest of “some 249 people during a raid on the Indonesian Democratic Party... Some of them have been tortured and many were held for days or even weeks in incommunicado military detention without lawyers or families. One was beaten, kicked, and had a truncheon pushed into his mouth.”

One of those charged with subversion, independent leader Muchtar Pakpahan is currently facing a lengthy jail sentence, possibly the death penalty, for insulting the president. “Pakpahans’ real ‘crime’ was organising workers to demand wage increases and humane working conditions,” The East Timor Action Network stated. “Through their sub contractors in Indonesia, Nike takes advantage of a repressive dictatorship that has always denied workers the right to organise independently. The Suharto regime uses its military to keep workers in line.”

In April last year Nike signed the Presidential Task Force Agreement on Sweatshops. Just after this a series of wildcat strikes occurred in countries where the agreement was not being applied. Thirteen hundred workers at a factory in Vietnam, 10,000 in Indonesia. Thuyen Nguyen, whose accounts of labour abuses in Vietnam were widely reported in the national media at this time, observed that Nike was always quick to discredit his reports by quibbling over details while ignoring the well-substantiated larger picture of abuse.

Four months later Nike did pull out off our Indonesian factories; the Campaign for Labour Rights suspects that this is less to do with concern for human rights, as NIKE claims, and more to do with cheap labour. They have, after all, subsequently increased production in China. According to Christian Aid’s book ‘The globe trotting sports shoe’ the abuse of workers is worse in China.

Being able to contact the outside world is vital to give empowerment it is only through sneaky clues [such as a Gap label being snuck out of a dodgy factory in Honduras] that the truth can be detected. Bethan Brooks, from Christian Aid, who co-wrote the book told Squall: “It is virtually impossible to get any new up-to-date and proven information from countries such as China.... We have no-one in the field out there.”

Links

Campaign For Labor Rights - https://campaignforlaborrights.org *

No Sweat - fighting sweatshop labour, in solidarity with workers worldwide - https://www.nosweat.org.uk

* Wayback Machine link