Space - The Final Frontier

Planning homes for the future has always been difficult. With increased awareness of green and brownfield building, the issues maybe getting confused. Investigation by Andy Johnson.

Squall 16, Summer 1998, pg. 16.

Walking in the middle of the road is generally acknowledged to present danger of fatality from either side. Which is why deputy prime minister John Prescott is to be pitied as he bumbles down the central reservation of the M1 - think about it.

Prescott has genuine green ambitions. But the cabinet rejected his draft white paper on traffic reduction as ‘too green’. His car-unfriendly, energy efficient, environmental village on the Millennium dome site receives zero credibility. But environmentalists cast him as the silent movie villain plotting to pour concrete over England's green and pleasant land - maybe he's the wrong target.

There are a few myths about the need to build homes for the estimated 4.4 million new households by 2016. The first is that Prescott is solely to blame.

The figures are old; they date from 1992. They are Tory figures and since 1992 over one million homes have been built. Tory attacks on Prescott over the greenbelt are therefore somewhat dishonest.

It is also important to note the figures are for household formation, not houses. A household being the number of people living under one roof - be it one or five. One building can provide a home to a number of households.

Although the figures have been gently bubbling away for five years it's only now they're causing any kind of interest. One of the reasons, according to expert insiders, is that the country is beginning to run out of space. On top of that, the level of housing needed is out of all proportion to the population, which is not growing.

The figures are reviewed every three to four years. The next revision is due in June, and they are expected to rise again - to about 5.5 million. Half a million of these are due to back-log; houses that have been demolished but not replaced. There are a further estimated half a million ‘hidden households' - couples living with their parents; grown up kids living with their grandparents.

In certain circumstances that might seem a good thing. But ‘hidden households' really translates as chronic overcrowding. In London alone, an estimated 45,000 people live in hostels, squats and bed and breakfasts. On top of that there are around 1,000 sleeping rough. The Association of London Government estimates 100,000 new, affordable homes are needed in the capital.

According to Shelter, the National Campaign for Homeless People, the need for new affordable homes nationally is running at around 160,000 a year.

Britain's population is not growing. The need for so many new homes is based on changing social trends. More people are living alone, not just because they're selfish misanthropes, but also because more are getting divorced and more are living longer.

They are trends, Shelter says, which cannot be denied. In their submission to the House of Commons select committee on housing, which is examining housing need, Shelter said: “They are substantiated both by Shelter's direct experience as providers of housing advice, and numerous studies."

A small proportion of the new households are also due to increased immigration.

The 4.4 million projection is therefore flawed but, nevertheless, it is also accepted as the best estimate there is. In his evidence to the Commons inquiry, Glen Bramley, professor at the school of planning and housing at Heriot-Watt University argued: “There is no alternative system that is so well developed."

This view is accepted by expert after expert, as well as campaign groups such as Shelter.

“We are satisfied there will be a very significant increase in the number of households needing housing," it says.

Labour MP for Stroud David Drew, a leading opponent of excessive green belt development, is willing to challenge the figure.

“We know the population is fairly stable. So most of the increase is from migration and single-person households. Are single people inevitable, and if so, are they a good thing?"

Some people think so. More single people are seen as good ways of regenerating inner cities. They are the ones who might want to live there.

Others argue the figures are a self-fulfilling prophecy. Just as more roads leads to more car use, they say, more houses will lead to more households.

Professor Bramley says that if you put houses on the edge of town that's where people will live. But, conversely, building less houses won't slow the divorce rate.

The biggest flaw in the projection is that it is based on past trends. Just because divorce rates have been rising for the last 20 years is no guarantee they will continue to do so.

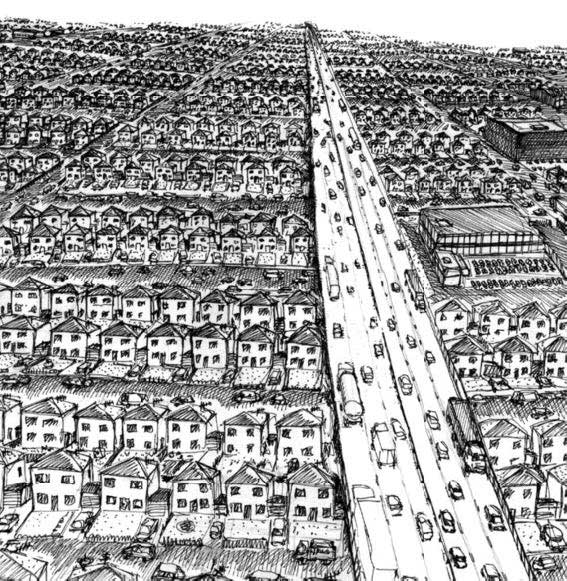

Experts also acknowledge that ‘predict and provide', where long-term estimates of demand are made on previous trends and then supplied, has sucked the life blood out of city centres - and scattered it across the countryside.

This is why, in February, Prescott replaced the ‘predict and provide' method to ‘plan, monitor, manage'. In other words, future projections should be assessed locally according to local need rather than nationally. But, until this picks up speed, the choice is between chronic homelessness or working on a 4.4 million assumption.

The government's target for building these homes on brownfield land is 60 per cent. Both the Campaign for the Protection of Rural England and Friends of the Earth argue this should be 75 per cent. But even with that figure, 25 per cent, or 1.1 million households, will find their way onto greenfield (as opposed to greenbelt) sites.

The big problem with brownfield land is that there isn't that much of it. There are massive swathes of it in old mining and ex-industrial towns, particularly in the north. But with the industry gutted out, there is no reason to live there.

North of a line between the Severn and the Humber there is too much housing. Social homes are being pulled down. Even if thousands of homes were built there, they would lie empty. Massive estates used to be built in the middle of nowhere, but with poor employment there are no shops, pubs, transport or entertainment and they become crime-ridden, drug addled ghettos. Conversely, in London and the south east, where everybody wants to live, there is hardly any brownfield.

The decision to build 10,000 new homes on the outskirts of Stevenage illustrates the problem.

Prescott also carries the can for this, although the decision was that of the local authority. (Stevenage has since suspended its plans and asked Prescott to examine them in the light of his statements over plan, monitor, manage.)

Faced with having to build 10,000 new homes, without any brownfield to speak of, the council could have put them on one side of town, greenfield but not greenbelt. On top of the houses they would have had to build road links to the town centre, installed sewers, power substations, street lighting, water and gas connection. Or they could have built them along an existing transport corridor with the fundaments of infrastructure in place.

The lesser of two evils happened to be on designated greenbelt land.

The other problem is that brownfield land costs a fortune to decontaminate and someone's got to pay for it. Whoever it is, the price of the house goes up.

There is also the small point that it is cheaper to build a new house greenfield than decontaminate brownfield land, or refurbish empty homes. Refurbishing empty homes is classed as ‘home improvements' and so carries a 17 per cent VAT rate. The Empty Homes Agency, which promotes refurbishment, is pushing to have this lifted.

One million of the projections are for affordable homes. The Liberal Democrats argue they won't be built as there isn't the money to pay for them.

Unless they are taken out of the projections, they argue, land will be released and then snapped up by greedy developers to build bland executive estates.

However, it's not all doom and gloom. The whole debate has re-focused attention on housing, where it hasn't been for two decades. Prescott talks of an ‘urban renaissance' with mixed thriving communities. His Millennium Village is supposed to be an example.

A recent report by the London Planning Advisory Committee (LPAC) said an extra 600,000 new homes could be built in London if densities were pushed up at the expense of car parking spaces.

Density is a key word for many local councils obviously keen to avoid overcrowding. But, according to LPAC, the most popular, and expensive, homes in London are at densities that wouldn't be allowed today. Three bedroom Victorian semis with front and back gardens were built before anybody owned cars. (They are expensive, like most property in London, because of limited supply).

Lord Rogers of Riverside, chairing Prescott's Urban Task Force into brownfield development, recently told the Commons housing inquiry what he hoped would be done.

He also talked about high densities, but not cramming. High densities save energy, they come from mixed use of shops, offices and different types of housing, which create communities.

He said car parks in London were a waste of space and should be built upon, and that we should be looking towards European models were cars in city centres were restricted, or electric, and car hire arrangements were made for long journeys.

“We're not just looking at housing," he said, “but at communities of which housing is a part. We're thinking how can we improve the quality of life".

Related Articles

A New Housing Bill - Homeless people vs the private rented sector - the new Housing Bill is reviewed by Joe Oldman - Squall 10, Summer 1995

Forget Politics - Let's Talk Homes - facile follies and new initiatives in housing, from long-serving member of the Advisory Service for Squatters, Jim Paton - Squall 9, Jan/Feb 1995

Marketing Madness & It's Allusion To Fairness - Corporatisation of the rental property market - Squall 4, April/May 1993