Watch With Big Brother

Both the police and MI5 already have a history of conducting intrusive surveillance on political protestors. Seamus O’Conner reviews the implications of new legislation which increases these powers.

Squall 15, Summer 1997, pp. 28-30.

According to the recently deposed Home Secretary, British police needed instantly available statutory powers of ‘intrusive surveillance’. And so, with Labour Party assistance, the Police Act was hurried onto the statute books in the last hour of a dissolving parliament.

Under the new Act, which still requires implementation by the incoming government, police will have the statutory powers to ‘bug and burgle’ anyone likely to provide information remotely relevant to an investigation into ‘serious crime’.

On the face of it, more power to fight serious crime might seem reasonable enough, but as a major adjustment to the law affecting civil liberties, the issue deserved far more consideration than it actually received.

With no bill of rights in the UK, the very existence of civil liberties is almost completely reliant on a fluctuating degree of parliamentary respect. If this respect withers in the shadow of other agendas, the population of the UK will have major cause for concern. The Police Act is the latest in a series of legislation which provides such cause, not least because of its wide definition of intended targets.

Under the Act, “serious crime” includes “conduct by a large number of persons in pursuit of a common purpose”.

“To be feared is not to be respected and without respect, community cannot exist.”

Regularly attracting over 5,000 people, Reclaim The Streets’ imaginative and socially-oriented ‘political parties’ easily fall within such a definition.

Following their successfully inspired ‘pedestrianisation’ of Islington in 1995, unmarked vehicles were deployed outside the RTS office in North London. People leaving the premises were followed, sometimes on the mountain bikes kept in the back of the trailing vehicles. In conjunction with this rather obvious tactic, RTS’s mail began arriving displaying overt evidence of interference. Letters were regularly re-stapled and labelled with Post Office stickers claiming the mail had been found ‘open in the post’. Following their most successful political party on the M41 last summer, the covert became the overt when Reclaim’s London office was raided by police and their computer hard discs confiscated.1

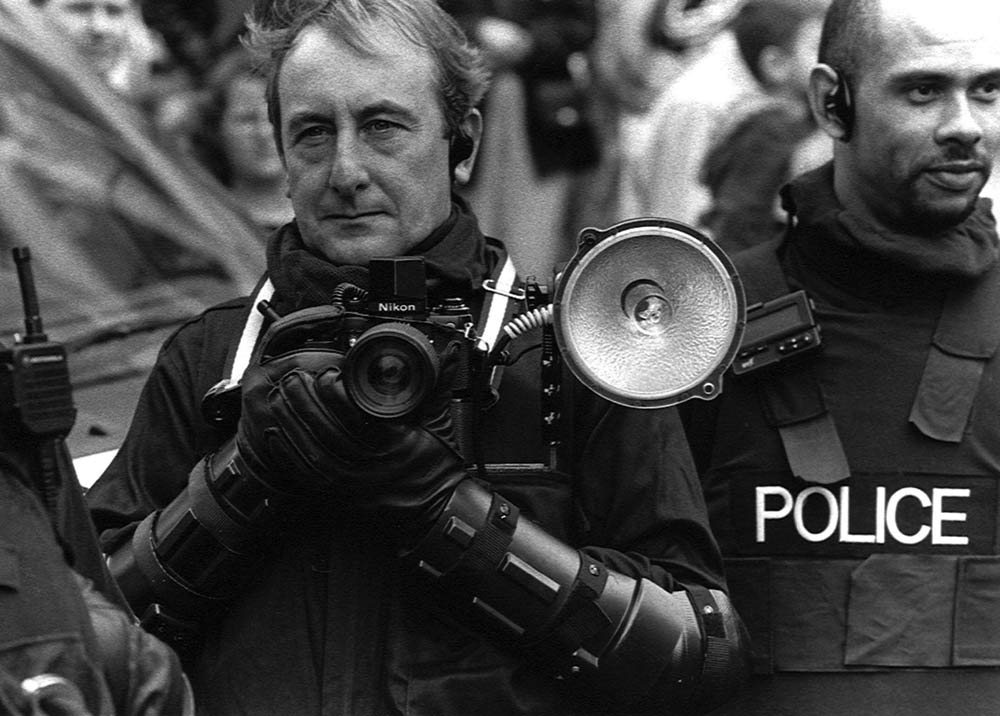

RTS events are also consistently attended by the Forward Intelligence Team attached to the Public Order Unit of the Metropolitan Police. According to reports in the Met’s magazine The Job, this team comprises 12 specially trained officers who work in uniform “to build a rapport between themselves and street activists so that the people likely to provoke disorder can be identified early in an event.”2

This “rapport” includes photographing and videoing individual protestors and matching them up with intelligence files. As the Police Review forewarned in July 1994: “The aim is to target known activists in the same way as convicted football hooligans - and to use the most modern technology available.”3 Individuals identified as regularly present on public demonstrations are then singled out for special attention.

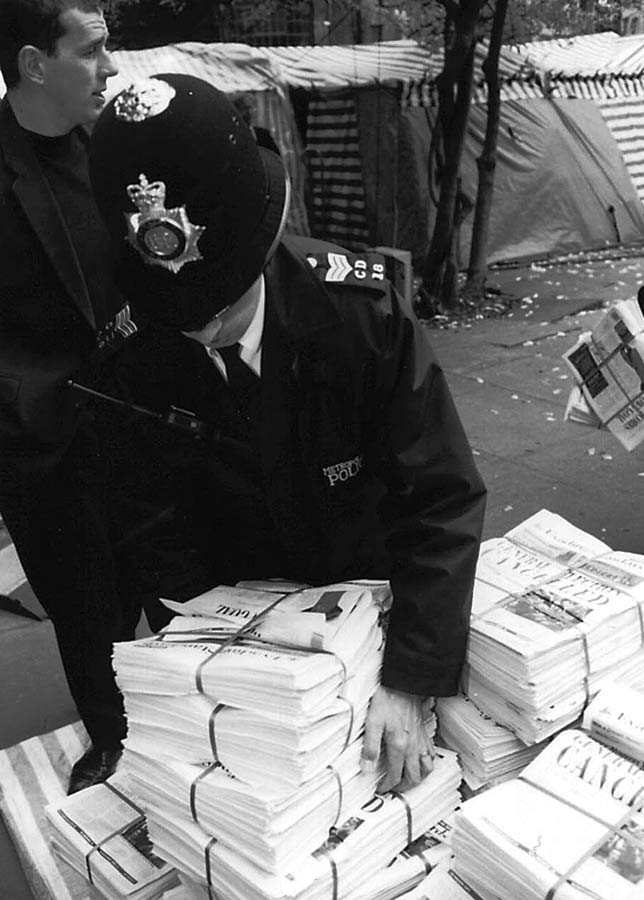

On the Friday night prior to the March for Social Justice in April, RTS printed 20,000 copies of a spoof version of the Evening Standard (click here to see online PDF). The intention was to ask volunteers to hand out 10,000 copies of Evading Standards to rush-hour commuters in central London. However, police found out the delivery point for the newspapers and, as the papers arrived, swooped to impound the lot. Two members of the Met’s Forward Intelligence Team, Sgt Mark Sully and Sgt Chris Fenot were present on the scene.

Although six volunteers were at the distribution point, Sgt Sully specifically arrested three regular RTS activists known from intelligence files. After taking them to Bow Street Police Station, he charged them with incitement to cause affray and highway obstruction. The three were bailed to appear at Walworth Road Police Station at 12.30pm the next day. When the activists turned up the next morning they were detained and further charged with breach of copyright on the Eros logo and a Metropolitan Police logo used on a spoof advert (altered to read ‘Multinational Police’). They were kept in cells for most of the day and weren’t released until 6.15pm, causing them to miss the march altogether.

Whilst the Metropolitan Police might claim “the relationship between these officers and the individuals will avert trouble before it happens”,4 in reality this has meant using intelligence in attempts to prevent demonstrations altogether.

When a relatively small action was planned by RTS to block a BP tanker leaving a London depot last December, very few people knew of the location. Protestors arriving at the site that morning, however, were greeted with a swarm of riot police and the action was abandoned.

It is now well-known that road protest stand-offs such as those at Twyford, M11 and Newbury have involved the deployment of private detectives, hired to collate intelligence on individual protestors. Up until March this year, the Department of Transport has handed over £2.2 million to Bray’s Detective Agency for just such a purpose.5 The passing of the Police Act now suggests other agencies are poised to take over this key surveillance role, with the DoT no longer stumping up the cash. As Inspector Gwyn Williams from the Met’s Public Order Training Unit said: “They [police commanders] must assemble their command teams and planning teams, learn how to get information and how to analyse it. They must also consider wider issues such as the effect of the disorder on communities and government departments.”2

As the March issue of the Police Review explained: “Forces are having to deploy increasingly sophisticated techniques in the policing of environmental protests.”6

Police reasoning for such sophisticated approaches were suggested by Chief Superintendent Mike Davies, from the Met’s Public Order Unit published recently in the Police Review. Davies described environmental protestors as ingenious, organised, articulate and well informed on environmental matters. They use flexible, sometimes inventive, tactics to achieve their aims.”6 Imagination, it seems, is a force the authorities find hard to counter with above board methods.

Chief Superintendent Mike Davies also addressed a recent seminar on the issue of policing environmental protest: “If a particular environmental cause were to spread countrywide, then mutual aid on a scale not seen since the miners’ dispute might once again be required.”6

The paramilitary police response to the 1984 Miners Strike is now well-known.7 In conjunction with these overt tactics, the mutual aid referred to by Mike Davies could well include the deployment of MI5. Indeed, evidence of MI5’s involvement in Margaret Thatcher’s war against Arthur Scargill and the Miners Union has long been in the public domain.8

Following the Security Services Act passed last year, MI5 now have a statutory “supporting” role in police investigations into domestic “serious crime”, using the same wide definition of ‘serious crime’ found in the Police Act.9

Prior to the Police Act, British police were unhappy with the superior powers of intrusive surveillance available to the security services for domestic investigations involving the police. The result was a ‘turf war’ between police and security services which induced some candid comments about the way the security services conduct their business. One senior regional crime squad officer was quoted in the Police Review: “Their lack of accountability may encourage them to go further than the police would. One scenario is getting gangs fighting each other, taking each other out and doing the job for us. In drugs there is a lot of inter-gang rivalry and violence already and it would not be hard to set them against each other. I could easily see a situation where local forces may be left to pick up the pieces.”10

Partly to placate police disquiet over the superior investigative powers of the security services, Michael Howard brought in the Police Act, essentially to equalise the intrusive surveillance capabilities of MI5 and the British police force.

In its list of new domestic investigative arenas, MI5 have expressed interest in “animal rights” activism, a brief which easily extends into all related environmental protest issues.

Surveillance operations on animal rights activists had previously been the sole territory of the Animal Rights National Index (ARNI), a section of the police’s Special Branch.

A confidential report on road protestors clearly demonstrates their extended interest. Written by senior special branch officers in early 1996, the report identifies 1,700 activists.11

Evidence revealed during the mammoth McLibel trial also provided some indication of the lengths to which Special Branch’s operative powers have already been taken. Sid Nicholson, Vice President of McDonald’s UK, revealed to the court that Special Branch freely offered to provide the Corporation with information about protestors attending anti-McDonald’s demonstrations. Nicholson, who at the time was also executive head of security, described how Special Branch even asked to use an office within McDonald’s headquarters from which to conduct a surveillance operation on a demonstration taking place outside in October 1989. According to Nicholson, such mutual favours were easily facilitated because “all the security department [McDonald’s] have many, many contacts with the police… they are all ex-policemen.” Indeed, Nicholson himself was a member of the police force for 31 years.12

Home Office guidelines issued in 1984 state: “Access to information held by Special Branch should be strictly limited to those who have a particular need to know. under no circumstances should information be passed to commercial firms or to employers’ organisations.”

Alarm over such casual management of covert surveillance information was also heightened in January of this year, following an official investigation into the large scale mis-handling of information by the police’s National Criminal Intelligence Service (NCIS).

The NCIS is a nationally based organisation responsible for overseeing police intelligence. Whereas previously it has operated as a section of the Home Office, the new Police Act imbues the NCIS with statutory ‘independence’ and new statutory powers of intrusive surveillance. It has also been given responsibility for overseeing liaisons between the security services and the police. The Director General of the NCIS, Albert Pacey, said: “I am confident these new arrangements will enhance our intelligence and operational capabilities.”10

Under legislation covering the interception of communications, senior NCIS officers are allowed to make notes from the transcripts of surveillance operations and take them away. They are required to return them at the end of each investigation.

During the course of a recent corruption case against a South East Regional Crime Squad officer, it was discovered that 900 police notebooks pertaining to a host of surveillance operations were found not to have been returned to the NCIS. No-one knows what happened to the information contained within them.13

The use of intrusive surveillance has not only been applied to protestors. A long history of surveillance targeting of travellers and ravers culminated in the infamous Operation Snapshot. This operation, initiated in 1993 by the Southern Central Intelligence Unit, gathers “any information, no matter how small, on New Age Travellers or the rave scene”. Leaked minutes of one of their meetings reveals the first Snapshot database had space for one million items of intelligence information.14

When questioned on a recent Radio 3 programme on dance culture, Detective Chief Inspector Jerry Dickenson, the head of West Yorkshire Drug Squad, was candid in his explanation of police strategies: “We are acting proactively now as we do in all aspects of criminal investigation. We raid the premises we collect and collate intelligence, analyse it, disseminate it, and act on intelligence-based operations. This is from informants, undercover police officers and any information we can get.”15

As revealed in a documentary made for Channel Four by Spectacle Productions to be broadcast this summer, evidence has come to light of covert surveillance operations carried out on properties occupied by Luton’s rave and social justice collective, Exodus.16 A long series of named police operations against the collective, one of which was deemed by a jury to have been a possible drugs plant, are a testament to the level of covert targeting already deployed against “large numbers of people gathered in pursuit of a common purpose”; dancing.17

Despite the obviously hidden nature of surveillance operations, evidence strongly suggests that environmental and social justice groups have been disproportionately targeted. With the extra legal weight given to the covert surveillance powers of both the police and MI5, an increased incidence of intrusion is inevitable.

The rapid move towards proactive protest prevention dramatically shifts the role of the British police force. With tactics increasingly dominated more by politics than by the local community, the police slide into a role as the front-line troops for a draconian ideology. The political forces behind these manoeuvres will undoubtedly be content if increasing numbers of people view the police as the enemy itself. Some members of the British police force are less than happy with this possibility. According to John Woods, a detective chief inspector in the Metropolitan Police: “There is a danger of officers becoming pawns in what is essentially a political game. Surely it is in the interests of the service to avoid such a path to destruction?”.18

Certain members of the police force have left as a result. John Alderson, ex-Chief Constable of Avon and Somerset Police hardly minces his words: “Howard is putting the building blocks in place for an East German-style Stasi-like force. It is there for future governments to build on. No government in my lifetime has ever given liberty back; it is not in the nature of governments to grant liberty.”19

Nevertheless the tide of surveillance policing and domestic encroachment by MI5 is being advanced with little consideration for the social consequences. According to Sir John Smith, deputy commissioner at Scotland Yard between 1991-95: “In the longer term the absence of privacy will be seen as a greater problem than that of crime itself.”20

Yer sauces:

- Squall 14 - ‘Police clampdown on RTS’

- The Job - newspaper for the Met Police. special supplement Public Order 21/7/95

- Police Review 22/7/94

- The Job 21/7/95

- Hansard 17/3/97 Col.417

- Police Review 21/3/97

- “A subject for concern is the move towards paramilitarism in the police. I accept that such a move has occurred.” Peter Imbert, ex-commissioner of the Metropolitan Police - Tony Jefferson The case against paramilitary policing (Open University Press 1990)

- Seumus Milne - The enemy within - the secret war against the miners (Pan 1995)

- Squall 13 ‘Unleashing the spies’

- Police Review 25/10/96

- Contract Journal - construction industry weekly. 18/1/96

- Squall 14 - ‘Special Branch help McDonald’s’

- Independent 22/1/97

- Squall 14 - ‘A criminal culture?’

- BBC Radio 3 Nightwaves 26/3/97

- Spectacle Productions presently untitled Channel 4 July 1997

- Squall 8 ‘Exodus - the battles’

- Police Review 27/1/95

- Red Pepper May 1996 Issue24

- The Sci-Fi Files BBC2 3/3/97

Related Articles

Read All About It - Police impound spoof newspaper Evading Standard - Squall 15, Summer 1997

Links

Evading Standards is viewable as a PDF on Libcom's online archiive - see here