International SQUALL

Famine On The Roof Of The World

With over a million of their grazing animals decimated by freak weather conditions Tibetan nomads face disaster, Tim Malyon writes.

Squall 13, Summer 1996, pg. 53.

Nomads in North Eastern Tibet, the old provinces of Kham and Amdo, are once again facing famine and destruction of their way of life, this time thanks to weather rather than enforced collectivisation by the Chinese.

Hundreds of thousands of herders face starvation - or migration to the lowlands to beg. Over a million yak and untold sheep, goats and horses have already died. With no fresh grass growing on the high plateau until June, another million may perish.

The disaster has been caused by a succession of ‘freak’ weather conditions - severe drought during last Summer, followed by early Autumn snowfall. A short thaw melted the surface, then the big chill arrived. Temperatures dropped to minus 45 degrees centigrade and froze the melting snow, covering the grasslands in an impenetrable layer of ice. Animals could no longer graze. Then came “severe and sustained blizzards, the worst in one hundred years,” according to the London-based Tibet Foundation.

At least ninety people have died, with thousands more suffering from frostbite and snow blindness. Herders tried to keep some animals alive by feeding them their own scarce food. The meat of animals which have died of starvation is inedible, although there are reports of boiled meat from carcasses being given to yaks. “It’s a human disaster, and a disaster for the economy of the region,” commented Philippe De Vestele from the charity Medecins Sans Frontiers (MSF) who has visited some of the affected areas. “Thousands of people have been left with no food and no cattle.”

Initial relief efforts were focussed on food relief and distributing blankets. Now money is being raised to restock the herds. A longer-term vision is also required: “Local people say these disasters are cyclic,” reports Phuntsog Wangyal from The Tibet Foundation, which is carrying out relief work through a Lhasa-based Tibetan organisation, the Tibet Development Fund. “The last one was in 1985, and there was another one in 1973. They say that every ten years there is a major disaster, every five years a medium scale disaster, and every three years there is a small-scale one. Temporary relief may not be the answer.”

Long-term plans include fencing off areas of grassland during the summer, to be grazed in winter. But this would barely have alleviated the present disaster due to the thick layer of frozen snow.

Making hay might help, but is hardly practical given the huge numbers of animals involved. Growing oats for winter fodder is another idea, but the plateau is so high (3,500-5,000 metres) and the soil so meagre that yields are low. The building of low, open-fronted cattle sheds has already proved effective in providing shelter and reducing animal mortality, especially amongst younger animals. And there are debatable suggestions that nomads construct permanent houses in lower areas where they can camp during winter.

On the western, Ladakhi edge of the Tibetan plateau (see Travellers In Another Place: The Himalayas in Squall 12), building emergency storage centres both for animal fodder and human food has proved effective in areas where winter camps remain within reach of the centres. Appropriate fuel-efficient stoves have improved fuel security, a major problem in the famine areas, and there’s increasing indigenous medical care. In Mongolia, felt-lined ‘gyers,’ (yurts), made from excess wool, stay warmer and save fuel, but require more animals to transport them.

One crucial question remains: Tibetan nomads follow a lifestyle which has existed for thousands of years. It is a lifestyle on the margins of survival. Is the 1995-96 famine part of a ‘normal’ cycle of disasters, or are Tibetan nomads suffering global climatic change which threatens their very existence? US meteorologist Elmar Reiter has suggested that massive Chinese deforestation on the eastern edge of the Tibetan plateau may be influencing global climatic patterns as well as local changes to the Indian monsoon rains.

If you would like to help:

Tibet Foundation

10 Bloomsbury Way

London WC1A 2SH

Please make cheques payable to Tibet Foundation Emergency Relief

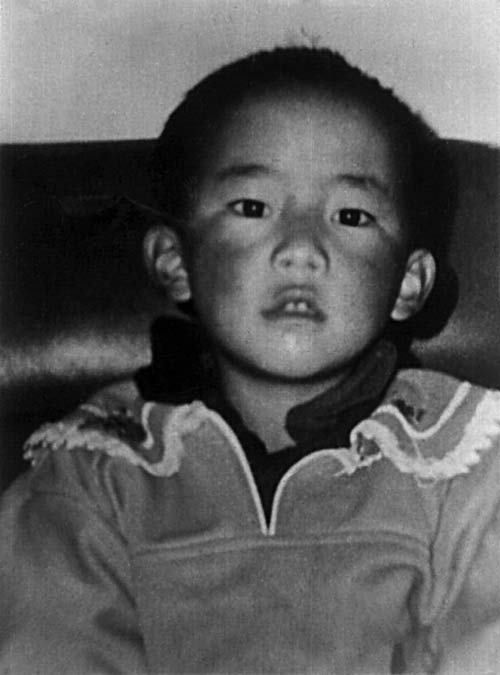

GENDUN CHOEKYL NYIMA, aged seven, has been recognised by the Dalai Lama as the 11th incarnation of the Panchen Lama, Tibet’s second most powerful ruler. He disappeared for over a year before the Chinese admitted to having put him “under the protection of the Government” in case he was “kidnapped by Tibetan separatists”. The Chinese only admitted holding the child in June after a formal request from the UN Committee for The Rights of The Child which has been investigating high death rates in Chinese orphanages. A UN request to visit Gendun Choekyl Nyima has received no response as yet.

Related Articles

Travellers In Another Place: The Himalayas - Tim Malyon reports on his travels to Ladakh and of the impact that the Chinese invasion of Tibet and western contact is having on the indigenous nomadic culture - Squall 12, Spring 1996

Tibetan Panchen Lama Still Missing - Chinese authorities won't disclose whereabouts of the boy chosen by the Dalai Lama as future leader of Tibetan Buddhists - Squall 12, Spring 1996

Increasing Oppression In Tibet - Tim Malyon reports on the latest Chinese crackdown on the Tibetan people - Squall 13, Summer 1996

Global Pledges For Free Tibet? - international support builds for Tibet - Squall 16, Summer 1998

Kowtowing To The Chinese - How governments across the world subjugated their own people in order to keep the Chinese president grinning - May 2000

Links

Free Tibet Campaign - http://www.freetibet.org