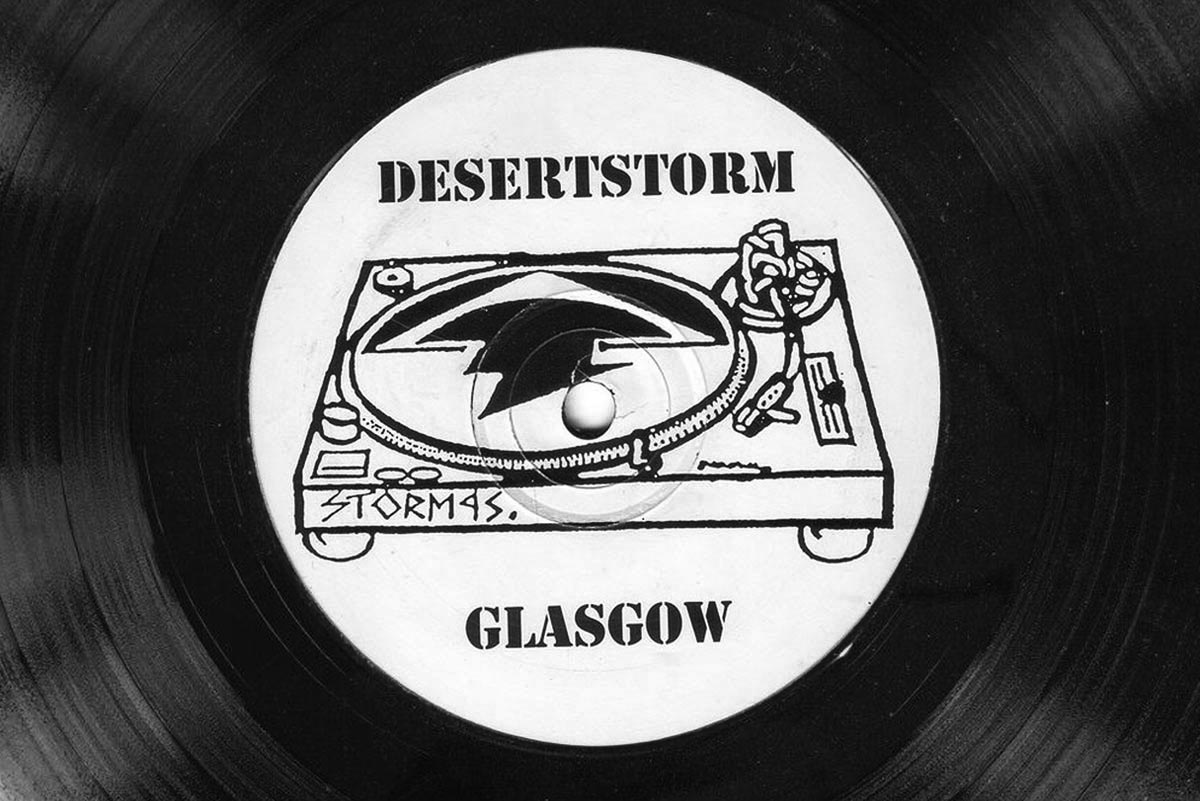

Desert Storm

Two part special on Desert Storm sound system by Ally Fogg and Jo Marshall:

Squall 13, Summer 1996, pp. 40-41.

Storm'in The Desert - Part 1

Ally Fogg meets Desert Storm, the sound system who took techno to the front-line in Bosnia.

Sound Systems do not have to seek trouble these days. Under attack from a parliament which considers them criminals, they work with the constant risk of arrest and seizure of equipment. Most party crews face all this for no more reward than seeing people dance.

While some party crews have sought a quieter life on the more hospitable Euro scene, Glasgow’s ‘Desert Storm’ have found welcoming crowds in the unlikeliest venues of all; the war-torn cities of Bosnia. On a recent ‘legit’ tour of British venues to raise money for their fourth trip in 18 months, in Manchester’s New Ardri club they shared with me a little of the World According to Desert Storm.

Although home base is still Glasgow, the five crew members I met each come from different cities. “Desert Storm isn’t really a crew,” explains Rob from Sheffield “it’s more of a ... Thing.”

“A bubbling blob,” offers Danny. “Yeah, people kind of drift in and out.”

At the centre of the blob is Keith, the only remaining founder member. He talks enthusiastically about the origins of Desert Storm, throwing ‘after-parties’ in Glasgow in early ‘91 against the backdrop of the Gulf War. The name was his idea, representing not only their ‘beats not bullets’ message, but their desire to be seen as part of an army: “It’s an anti-establishment thing, we want to show them we’re organised, but for our own ends not for theirs”.

Desert Storm decor does not follow the usual style of techno nights, all trippy fractals and tie-dye wall hangings. Instead they prefer a mass of camouflage netting, with khaki and black the dominant colours. The effect is powerful, Desert Storm gigs feel like they are taking place in a bunker with a civil war outside. The visual impact of a Desert Storm gig drives home the concept of a revolutionary culture boiling under the surface of modern Britain. In the beginning the parties had an entrance fee, but this was attracting problems: ”We were starting to get some really dodgy people hanging around, we had to hire our own shady security and it was all getting out of hand so we just knocked it on the head for six months. We went to London and met Mark from Spiral Tribe, and he persuaded us that free parties were the way forward. So we went back and built our first RDV (Rapid Deployment Vehicle) which was a camouflage Transit with a 1.5K rig on it. We could just drive in anywhere and start playing, and that’s basically how we’ve operated ever since.”

"At one point a policeman came up to tell us to turn the music up but to turn off some of our light because we were attracting shell-fire."

By 1994 the campaign against the Criminal Justice Bill was politicising ravers everywhere. Desert Storm were the only sound system to apply for permission in time to play on the July march, and consequently entertained an audience of some 70,000 in Trafalgar Square on a glorious summer’s day. One of them, James from Nottingham, was so impressed he tracked them down in Glasgow and has been a regular DJ ever since. Three months later this celebration of youthful freedom was overshadowed in Hyde Park by possibly the only riot in history to have been started by police determination to stop people from dancing. Keith recalls:

“Amid all the mayhem we’d broken down but we were still playing. There were riot cops everywhere and this crazy Glaswegian called Paddy stuck his head through the van window and said ‘I’ve got to have your phone number’. A week later we were home in Glasgow and I got a phone call from the same guy asking if we wanted to go to Bosnia in three weeks. I mean, what could we say? It was definitely fated, we just had to go.”

The resulting trip took them to Tusla with a Workers’ Aid convoy for the most exciting New Year of their lives. James describes the events of the evening: “We started playing on the move and we had thousands of people following us through the streets in two foot of snow and minus 10 degrees. We played one techno record with a chorus that went ‘get going to the beat of a drum BANG!’ and all the soldiers fired their AK-47s in the air ‘kakakakaka’ and it was such a fucking buzz it was incredible. We played the same record about ten times. At one point a policeman came up to tell us to turn the volume up, but to turn off some of our lights because we were attracting shellfire. The front line was only about ten kilometres away.”

Three trips later and the desire to take techno to the front line is as strong as ever. The ethics of taking a party to the most miserable man-made hell in Europe is an on-going source of debate, and not only among themselves. Danny admits: “It’s something that comes up repeatedly when we’re collecting money, how can we justify taking a large van all the way to Bosnia with only ourselves and a sound system. We sometimes have doubts ourselves, but then I think back to that first New Year in Tusla and I know we’re doing the right thing. The reality out there now is that most people have food and the bare essentials. Everyone from UNHCR to Worker’s Aid are sending convoys of lorries, and the main thing people are crying out for is any kind of entertainment at all. There’s also a youth element. Most of our money is raised among young people here in the UK and most of the people who go to the parties there are young. What we do is a cultural gift from the youth of Britain to the youth of Bosnia.”

While the Bosnia trips rightly dominate the legend of Desert Storm, stories abound of their adventures across Britain and Europe along the way. There was the ‘Technival’ in France, where a gigantic convoy from Paris led to a farm in a little town called Bresle where the farmer was overjoyed to see the ravers tramping down his field. It turned out to be a peat field and normally he had to employ people once a year to tramp down the grass before he could cut it. Shortly after the Mayor arrived atop a lorry full of water. Local by-laws required the townsfolk to show hospitality to any gathering of more than a thousand people whether invited or not. Last October the RDV went RTS as the Storm entertained 600 party-goers at a Reclaim the Streets party in Manchester, eventually leading a dancing parade through the heart of the city to the steps of the Town Hall. ‘That was fucking amazing,” recalls Danny, “We never thought we’d get away with playing on Deansgate. When I went to play the first record my hand was shaking so much I couldn’t put the needle down. But then when we started playing this tingle came up through everybody’s fingers and suddenly it was like there was an electric energy pulsing up from the crowd. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

Desert Storm’s willingness to take their chances with the CJA, the TSG or the AK-47s may seem to verge on the foolhardy, but the whole crew have the confidence that comes from knowing what they do is the right thing to do. Keith talks easily of ‘fate’, a suitable theme tune for Desert Storm would be a hardcore remix of ‘Que Sera, Sera’. He becomes at once animated and angry when reminiscing about visiting Mostar, where a glorious medieval city has been devastated by the war. “Just about the only building that hasn’t been hit by mortars or rockets is the Ganja cafe. In amongst all this misery and destruction you can still score, have a coffee and look out over the ruins. Is that fate or what?”

So what next for Desert Storm, I ask Rob. “Well I don’t know about anyone else, but I fancy Chechnya myself!”

Storm’in The Desert - Part 2

Jo Marshall travelled to Bosnia with Desert Storm, experiencing first-hand the need to dance.

I first went to Bosnia as a driver with the Workers’ Aid convoy to Tuzla. It was a diverse convoy comprising French, Spanish and dodgy old British food trucks, a delegation of teachers and Desert Storm sound system.

There were many, both on the convoy and back home who doubted the necessity or relevance of a sound system. However, I had been part of the Demolition Sound system in Manchester and believed strongly in the political and cultural power of music and free parties. Desert Storm had joined up with Workers’ Aid the previous year, had raised the money for a truck, and had driven it, with food-aid and hospital supplies and their sound system, to Tuzla in time for Christmas. Their mobile Christmas party, driven around the snowed up city, was more appreciated by the people of Tuzla, running out of their houses to dance in the streets, and remembered for longer than the food parcels they brought.

People don’t realise during war, even a vicious civil war like this one, life still goes on. People try to get on with their lives as best they can. The bars are still open, people try to get to work, to school. If anything, when your backs are against the wall, the need to party together is greater.

The Bosnian people were not fighting for gain, glory or patriotism, but for their lives and their town and the lives of their families. We have all seen the fate of the unarmed civilians of Srebinise. They felt they had been snubbed and forgotten by the rest of the world.

The youth of Tuzla were aware of the revolution in dance music that had been sweeping Europe since the start of the war. But because of a war not of their making they were unable to experience it.

For a Scottish sound system to drive 2,000 miles across Europe in a dodgy old Leyland truck, through six borders, Croat bandit territory, UN road-blocks, the front line and ‘snipers alley’ to play the best in bangin’ British dance music, was more than appreciated for the act of friendship and solidarity that it was offered as. They didn’t ask: “Why are you here?” they asked, “When are you coming back?”

We were leaving Tuzla after the summer convoy through the only route open in and out of the country, ‘ snipers alley’. It was a road along the bottom of a valley with Serbian gun and sniper emplacements on the top of the ridge. The convoys had to drive as fast as they could along this valley, at night with their lights off in order to avoid being hit. We were at the checkpoint at the safe area in the mountains, waiting to go through. There was a delay as the previous convoy had been hit. A Bosnian soldier came up to me, you could always tell the Bosnian soldiers, they always wore trainers, had no proper equipment or old police rifles. His eyes looked tired and resigned. More than likely most of his family had been interned and his friends and classmates killed. He said to me: “You bring food, thank you for bringing food, but we need guns and bullets, they have tanks and planes and we have nothing. If we could defend ourselves you would not have to bring food. You go back and tell that to the people in your country.”

Since the Dayton agreement, things had changed in Bosnia and we wanted to go back to celebrate with them their first Christmas of peace. The food shortages were largely over and aid was pouring in from the big, publicly financed agencies. For the first time it was possible to drive to Sarajevo, previously only accessible through a mile long, four-foot wide man-made tunnel under the airport. this was Bosnia’s capital, ethnically united in the defence of their city that had been completely under siege and blockaded for two and a half years. Sarajevans had been without water, electricity, been shelled and shot at constantly, but still managed to retain some of the cosmopolitan and liberal atmosphere the city had before the war.

There is not enough space for all the stories and comedy fuck-ups that we had to go through to get there but get there we finally did, two weeks late.

It has to be said the Sarajevans we met were initially sceptical about our reasons for being there and what we were up to. Since the peace accord the city had been swarming with Christians, media types and minor celebs wanting to do something, or be filmed/photographed doing something for the poor Bosnian people. Apparently they were particularly sick of Americans trying to patronise them and give them teddy-bears.

Any doubts we may have had evaporated when we saw the club Obala throbbing on the Saturday night with hundreds of sweaty Bosnian ravers stomping and screaming for more.

Attitudes warmed further after an interview we gave on Radio Zid (Wall Radio), Sarajevo’s youth, independent, and only non-government radio station (and the only one listened to by anyone under 30). The DJs played a damn fine set live on air then we explained that we were British antifascists (I had never defined myself as such before) and that, not having access to money or large resources, music ws the only way that we could give something significant to the people of Bosnia.

At the end of the interview the presenter asked: “Is there any message you have for the people of Sarajevo?” That completely stumped me, then, remembering the soldier at the checkpoint in the summer, blurted out: “During the war, we brought food, medicines and music, you needed guns. I wish that we could have brought guns. I’m so ashamed of my Government. I’m so sorry, I wish that we could have done more to help.” And I still do.

Thanks to: Club Obala, Sarajevo, Emire and the Metelkova squat Llubiana, Bob at Workers Aid and Keith.

To understand the Bosnian war, read Seasons In Hell by Ed Vulliamy, the first journalist to see the Servian concentration camps.

Related Articles

Top Ten Free Party Tunes - with Desert Storm EP competition - Squall 13, Summer 1996