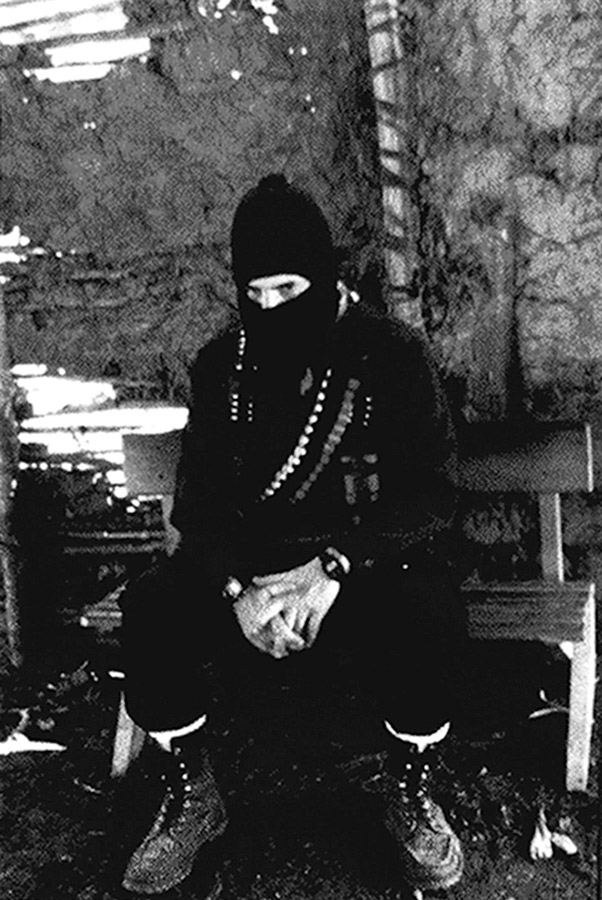

Pic - unknown.

International SQUALL

Zapatista!

When vested land interests and exclusive democracy became too entrenched in Mexico the peasants and freedom fighters took exception. Ursula Wills-Jones reports on the people’s revolution.

Squall 12, Spring 1996, pp. 46-47.

December 31st, 1993. The frost was inches thick on the ground. We’d gone to Avebury, just me and a friend. There was nobody else there. We walked round the stones. It was very quiet. Approaching the stones, hundreds of faces loomed out of them at us. Our footsteps made black marks on the white, rigid grass. In the morning, we watched the sun come up over the stones. It was still freezing.

Somebody else was awake that night, though I didn’t know it at the time. Apparently it was freezing that night in San Cristobal de Las Casas, too. Mexico is six hours behind our time, so the city must have fallen at just about the time we watched the sunrise. They just arrived, unannounced, out of the mist, out of the mountains, out of 500 years of obscurity, and by the time the world woke up on New Year’s Day, San Cristobal, a modern tourist city with 100,000 inhabitants, had, along with five other towns, been seized by masked Mayan rebels.

"Antonio dreams that the earth he works belongs to him. He dreams that his sweat is paid with justice and truth. He dreams there is a school to cure ignorance, and medicine to frighten away death. He dreams that his land is free and that reason governs his people and his people govern by reason. He dreams that he must struggle to have this dream, he dreams that there must be death to have life. Antonio dreams and he wakes...

A wind rises up. Something tells him that his desire is the desire of many and he goes to find them.

The viceroy dreams that his earth moves from a terrible wind. He dreams that that which he robbed is taken from him. He orders murders, imprisonment, the building of more jails.

In this country everyone dreams. Now the time has come to awaken...”

From 'Two Winds, a storm and a Prophecy' by Subcomandante Marcos.

I didn’t know this at the time, of course. It was that evening when I turned on the radio that I heard that an insurgent army, unknown and unheard of, had emerged in the State of Chiapas, Southern Mexico, demanding freedom for the indigenous people, the repeal of the North American Free Trade Treaty, bread, land and democracy. If history had ever ended, it had just started again. I couldn’t remember the last time I laughed so much.

If I was surprised, I wasn’t the only one. Almost all the news reports carried the phrase “a previously-unknown group calling itself the EZLN”. For ten years in the mountains an indigenous army had been growing, and almost no-one had known. But if Central America was a familiar hotbed of Communist revolution in the 1980’s, this one was very different.

The Zapatista National Liberation Army didn’t invoke the names of Marx, Lenin, or Mao. Instead they looked to Mexico’s revolutionary folk heroes, naming themselves after Emilio Zapata, the peasant hero of Mexico’s unfinished revolution, which had taken place in 1910. They weren’t interested in taking power, they claimed, demanding instead a transitional government to bring democracy and end the seventy-year dictatorship of Mexico’s ruling party, the PRI.

One of their main demands was the redistribution of land. Although Chiapas is a productive and fertile state, huge tracts are owned by large landowners, usually of European descent, while the indigenous Mayan poor scratch out a living on inadequate mountain slopes. Adult malnutrition in Chiapas was as high as 80 per cent. The Zapatistas control of much of the state, or simply their example, did provoke a certain amount of land redistribution to take place, and by the end of 1994 more than 100,000 acres of land had been occupied by peasant land invasions.

The Zapatistas internal dynamics also marked them out from earlier armed movements. While their military commander and non-indigenous spokesman, Subcomandante Marcos, became their most obvious figurehead, the actual leadership of the army remained in the hands of an elected committee, the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committee, made up solely of indigenous people from Zapatista communities. They were also refreshingly free from traditional Marxist dogma: Marcos was lambasted by the government press after he joked to an American newspaper that he had once been sacked from a job for being gay. Many people saw them as a product of Catholic Liberation theory, but some of their habits would certainly have appalled the Pope. A third of the insurgent force was made up of women, and female Zapatista leaders cheerfully admitted that they encouraged them to take the pill. Marcos confirmed that it was the EZLN’s policy to ensure that safe abortions were available for any female guerrilla who needed or wanted it.

One of the Zapatistas other assets was that un-Communist characteristic, a sense of humour. Marcos’ communiques, written on a laptop computer somewhere in the jungle and faxed out to the press, were alternately poetic, self-depreciating and witty. Not only that, but they handled the press with a skill that would have most professional spin-doctors weeping with envy. The New York Times dubbed them ‘postmodern revolutionaries’. In fact, the media was probably their main weapon, and rather more effective than the ancient, single shot rifles that most of the guerrillas carried.

The Zapatistas honeymoon period didn’t last. In Dec ‘94 the Mexican economy crashed, and the government lost their patience. They sent in as many as 20,000 well-armed federal army troops into Zapatista controlled areas, and issued arrest warrants for the leaders. The Zapatistas didn’t try to fight it out: they just retreated into the mountains, taking much of the local populations with them.

The government also attempted to deflate Marcos’ huge popularity by ‘unmasking’ him, revealing him to be Rafael Guillen Vicente, a former university lecturer. Unfortunately for them, Guillen’s biography showed nothing more sinister than the fact that he was educated, intelligent, principled, and had given up a comfortable middle-class lifestyle to live in poverty. As hi-tech planes bombed indigenous villages, demonstrations filled Mexico City, chanting ‘we are all Marcos’. Marcos’ response to his ‘unmasking’ was to quip “Is this new Marcos handsome? Recently they’ve been trying to make out I’m ugly, and it’s ruining my female fan mail.” After a week, the offensive was called off, but large tracts of land which had previously been EZLN territory were now controlled by the army. The long grind of peace talks began again.

One thing is certain, however. Mexican politics has never been the same since the uprising, nor is it likely to be so again. The Zapatistas claimed that they wanted to tear off the first world mask which the country had put on; in that, they could hardly have been more successful.

“Ever since January we live in a new Mexico,” wrote Elena Poniatskowa, a Mexico city journalist. “Before, we scarcely spoke of misery in our country, and the poor were easily ignored. The poverty of ‘the others’ became part of daily life - it was our landscape.” In the summer of ‘95, a survey showed that 82 per cent of Mexicans believed that the basic demands of the Zapatistas were the basic demands of the Mexican people.

It’s also possible that the uprising will have repercussions beyond the boundaries of Mexico. As the first organised revolt against the New World Order, The Zapatistas proved that despite the death of Communism, resistance to the oppressive hand of market forces is by no means over - in fact, it is probably just beginning.

Related Articles

Zapatista! - update from the jungles of Chiapas by Ursula Wills-Jones - Squall 14, Autumn 1996

Digging In Chiapas - Shaymus King is a member of the Easton Cowboys, a team of football-playing activists from Bristol. He sent this dispatch from the Chiapas jungle during a recent away fixture against the Zapatistas - March 2001

Viva Zapatista! - In Mexico for the Zapatista march to the Mexican capital in March 2001, Shaymus King interviews a young Zapatista guerilla in La Morelia - 11th April 2001