Rough Streets Initiative 2

Much is talked about street homelessness; some flippant, some concerned. But, in real life, sleeping on the streets is a far more intense state of life than many realise (or would want to). This series of two articles takes a personal look at two street-level attempts to help out.

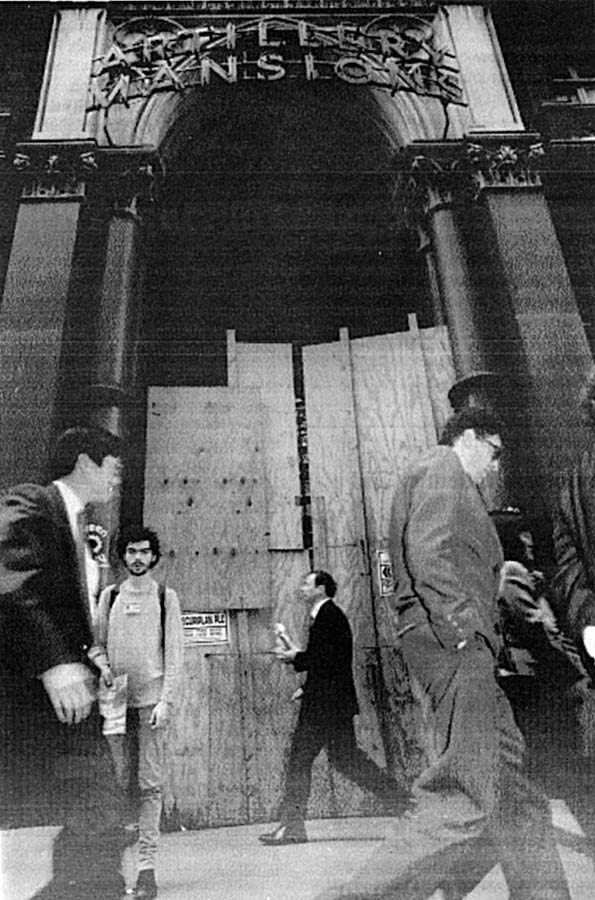

Artillery Mansions

by Jim Carey, one of a team of squatters and rough-sleepers assembled by necessity.

Squall 11, Autumn 1995, pp. 74-76.

As anyone who stayed from the start to the finish of the Artillery Mansions squat occupation will tell you, a lifetime's education was crammed furiously into six weeks.

I was introduced to the project only three days before the three thousand room mansion was squatted on February 18th 1994. My job was simply to run a temporary off-site office on the day of the occupation, fielding media enquiries and facilitating legal back-up. One and a half mad, inspired and dangerous months later, I stood in court for four and half hours arguing with the legal representatives of Great Bear N.V., the multi-national company which had left most of Artillery Mansions empty for over 12 years.

To start with, the squat occupation of Artillery was a stunt designed to highlight the coming of the Criminal Justice Bill, the farce of high numbers of empty properties, high homelessness and criminal sanctions against squatting. The building was in a perfect location, surrounded as it was by the Houses of Parliament, the Home Office, the Department of Environment, New Scotland Yard and the bastion of Damn Shirley Porterism - Westminster City Hall.

Banners were hung from the balconies, visible both to the hundreds of people walking up and down busy Victoria Street and to the dignitaries of one sort or another who were regularly chauffeured past its doors. Media coverage was extensive, with every major newspaper, television and radio station running features and documentaries on the place. A parliamentary question was asked about the occupation and Betty Boothroyd, speaker of the House of Commons, dropped by to give her verbal support. "I can't sign the petition," she said. "Because I have to stay neutral."

But a small number of project instigators were not happy that a three thousand room mansion was being occupied simply as a media stunt, when hundreds of homeless people slept in the doorways of the street it was situated on; and so an idea was born. The Government's Rough Sleeper Initiative was itself simply a media stunt and came no where near dealing with the escalating number of people forced to sleep on the streets. So, we decided to run our own Alternative version - The Artillery Mansions Alternative Rough Sleepers Initiative.

Flyers were made up and distributed to people dossing in doorways, inviting them to come and select a room. Word got round and the numbers of people coming into the building swelled to over a hundred.

Now imagine a three thousand room building with no electricity, open to the street and full of people, some of whom had not had a roof over their head for eighteen years. We had prostitutes running tricks from the building. We had every kind of drug addict in the book and not in the book. We had runaway children looking for sanctuary and we had mentally ill, homeless people largactiled up to their vacant eyeballs and then turfed out of hospital onto the street. One guy showed up with a hospital towel round his waist. He had run away from a local mental hospital and the police were after him. He slept one night and was gone. The police arrived the following day with a search warrant to look for him. The warrant, which I still have, had a specific room number on it; odd because no-one knew the room numbers and hardly any of the flats still had numbers on them. When we worked it out, the room number on the warrant was indeed the room he had stayed in for the night. So we had undercovers in there too.

A petition collated on a table outside the front door gathered over 3,000 names, including local constables who both sympathised with what was going on and had the guts to stick their necks out and put their names down.

Also on the outside of the building, we put pasted up copies of the front page of Evening Standard from January 13th 1994. The lead story was of Shirley Porter and the Westminster Council gerrymandering scandal, involving "the export of homeless people out of the Borough". The headline ran "Unlawful, Disgraceful, Improper". We had a visit from the Council's billboard officer who told us to take the posters down. We refused and told him to go away and prepare the paperwork - we did not see him again.

Indeed I was told by one of the many legal people mixed up in the history of Artillery Mansions that at least one of the reasons it had remained empty was that Westminster Council were concerned about what kind of homeless people would be housed there. The Empty Homes Agency which have offices just up the road from the Mansions, had made strenuous efforts to negotiate the use of the building for short stay accommodation for homeless people. A lawyer told me that these efforts had been stalled by Westminster Council's insistence that it only wanted "professional people" to occupy the Mansions.

In the first collective meeting of the new Artillery occupants, it was strongly suggested that we keep the building alcohol-free. Then one of the rough sleepers spoke up. "Ban alcohol," he said, "and you ban 95 per cent of the rough sleepers on this street". It was cracking inside information from someone who had never been to such a meeting in their life. The decision was changed to no alcohol in the communal places of the building, and we all proceeded to do our erratically successful best to make sure this 'policy' was adhered to.

But as the first novel fortnight drew to a close, more and more of the original 'media stunt' occupiers began drifting away, leaving the precarious balance of the project to lurch towards the wild side of the fence. By this stage, the publicity around the building and the occupation was attracting every coupster in the book. Scrap merchants came from miles around; you'd come across them loading up their van at one of the entrances with fireplaces stacked in the hallway.

In their eyes they were just making a living but to those trying to hold the place together they were vultures. One day a scrappie stole a brass fitting, worth only about £3, but the result was a gushing water leak from the roof. It was only stopped when the fire brigade arrived to seal off the water supply to the building. For a while there was no water in the toilets or kitchen because of that disrespectful piece of opportunism.

But despite the mayhem, something powerful happened in Artillery Mansions. Something that will remain in the memories of all those who stuck with the project. From amidst all the muddied chaos came some unforgettable jewels. A tenuous but very real community of right-on rough necks and ragamuffins rose up to make sure the project never became the blazing nightmare it always threatened to be.

There was Pugh, who always claimed to be just a musician strumming his guitar but who took on more overnight guard shifts than anyone. And there was Stuart, on the street for ten months since arriving from Scotland looking for a job. He hauled up a sofa and a few chairs to a third floor flat and decorated the first room of his own he'd ever had. He became one of the most articulate spokespersons for the cause of homelessness that I've ever heard, astounding journalists and documentary makers with his observations. "It's the first time I've had the opportunity to tell them what it's really like," he said to me once. One time when a BBC camera crew walked into his room, he told them to get out and knock next time. They did so and he invited them back in and bade them make themselves at home. Then there was Stan, an ex-M11 security man who'd been sacked from his job for disinterest, and was now homeless. He ran round like an earnest blue-arsed fly helping to hold it all together.

One guy showed up with a hospital towel wrapped around his waist. He had run away from a local mental hospital and the police were after him.

Then, manning the door and taking on the role of 'head of security' was big and gentle Hawk. One day two young girls, who'd previously been told to go home (we tried to encourage young runaways not to stay unless absolutely necessary), arrived back at the Mansions. We managed to find out that they lived in Ealing, West London, so Hawk said he'd make sure they got back home safely. On the way to Ealing, he bought them a hamburger each with the little money he had. Because one of them refused to give him her address, he dropped her off at Ealing Police Station and took the other one to her home. On the way back to the tube from dropping the second girl off, Hawk was accosted by police, who threw him against their car, searched him and placed him under arrest. After being left off at Ealing Police Station, the first girl had told police that Hawk tried to rape her on the journey. Hawk was badly shaken, even by the idea that he should be accused of such a thing. He'd been living on the streets for eighteen years; he didn't have much but he had his dignity. We got him a lawyer who explained the situation to the police and they agreed that the girl had told lies out of spite. There was no medical evidence and the girl's story was inconsistent. Hawk didn't recover from that incident, he grew withdrawn and disappeared a couple of days later.

Another saint in the crowd was a woman called Pat. She had two children living somewhere in Dorset but had been living on the streets of London for many years. She made it her task to look after the child runaways and still found time to clean the toilet floor nearly everyday.

Then there was Bill, a jolly alcoholic of about 65, who at one time in his life had been a ship's cook. He took great pride in cooking up two huge pans of soup each night for everybody in the building. Every evening he'd ask me to go and get a bulb of garlic "and a little can of the drink". Hence forth he was known as Garlic Bill, a name that brought a warm dignity to his face. Some of the resident rough sleepers used to take his soup before he'd finished cooking it and he'd go mad. I found him on a couple of occasions rolling round on the kitchen floor grappling with some drunk geezer who'd evidently shown no respect for Garlic Bill's pride in his cuisine. All this and he had medically diagnosed angina too! He never ate any of his own food - he said he couldn't stomach solids, he could only drink.

There were many other saints and necessary sinners that shone through during those six weeks, finding a dignity hard to keep in the forgotten doorways and park benches of London. Which is just as well because there is an argument that one and a half months with a room of your own is worse than none at all. It constantly nagged my conscience that perhaps Artillery Mansions would be just a titillation for the rough sleepers which it housed; a reminder of what they didn't have the rest of the year round. The counterbalance to this feeling has come since the project finished. I know of four rough sleepers who now squat - prior to Artillery Mansions they did not know how to. And I have since met with others who only express fond memories of the Artillery and their chance to make a stand.

We won the first court case after one and half hours of arguing that the owners had not proved their rights of ownership of the whole block and that they had failed to look after four pensioner sitting tenants who were scattered in the back block amid the dead pigeons. The pensioners had been waiting for eleven years to be rehoused by the multi-millionaire company that owned the building.

The judge adjourned the case and ordered that some of the documents we'd found, and built our case upon, should be handed over to the owner's legal representatives. I was due to meet their representatives at 10 am the following morning.

A tenuous but very real community of right-on roughnecks and ragamuffins rose up to make sure the project never became the blazing nightmare it always threatened to be.

When I arrived at 8.30am, the front foyer was full of people singing and slopping cider everywhere. I got a mop and asked them to move downstairs so that I could clean the floor. They took offence, took a couple of swings and then literally booted me up the arse and out the door. So there I stood outside the building with a sore arse, waiting for these representatives to show up. And out comes one of the drunk revellers in tears. "I shouldn't hurt my own, I shouldn't hurt my own," he cried and hugged me several cider swilling times. He'd been homeless before, he told me, but then got married and sorted himself out. He showed me a photograph of his three pigtailed daughters. The marriage had broken down, he'd taken it badly and been sectioned into a mental hospital. "Eleven fucking milligrams of chlorpromazine a day," he balled through his tears. "And now all I've got is this," he said nodding towards his plastic mug of cider. He hugged me several more times and apologised for hitting me - I could hardly speak but I managed to tell him that the last thing I was going to do was hold it against him.

During the final weeks of Artillery Mansions I visited and telephoned charity after homeless charity trying to find someone to help cope with the increasingly dramatic and hardened cases that were making a home amid the chaos. None of them could help. Some expressed sympathy, but those that were honest with me said that the situation at Artillery Mansions was far too raw to send people down to. It didn't help the workload but it was an explanation I could understand. In many ways 'raw' was an understated description of the Artillery Mansions Alternative Rough Sleepers Initiative.

We lost the second court case. To be honest, those that were still there right to the end were relieved. But we still fought for four and a half hours in court, answering the lies sworn into an affidavit by the owners of the building. They had claimed we had smashed up the building and were the cause of a local nuisance. But having left it empty for eighteen years and open to the street, we used photographs to show the judge that the state of the building was largely a result of the owner's neglect. We had statements from the pensioner sitting tenants and ex-residents of Artillery Mansions about the years of neglect and legal run-around that the owners had put them through. One 70-year-old man lived in a one bedroom flat on the fourth floor of the back block. Despite having severe emphysema, he had to climb those stairs everyday, and go past pigeons carcasses and guano to his isolated flat. The lifts did not work.

We also had statements from local shopkeepers who used to give us boxes of sandwiches and we had the 3,000-plus name petition, sworn in as court evidence.

A number of the rough sleepers, shortly to be returning to the street after a one and a half month spell with a roof, addressed the judge. He was as visibly moved as I have ever seen a poker-faced judge to be. Every lie and masking of the truth sworn by the owners was deconstructed. They knew there was a truth to hide because they'd got the judge to ban all journalists from coming into the court room.

At the end of four and a half hours, the judge said he had no choice under law but to grant possession to the owners. However, in his sum up speech he said he had every respect for the way the legal case had been fought on behalf of the occupants, every respect for the Alternative Rough Sleepers Initiative and every respect for the street sleepers who had stood up for themselves.

Outside the court, the eight legal representatives who had fought on behalf of the owners and were each earning an estimated £1,000 a day, came up to me.

"We'd just like to say we thought you conducted your legal defence very well. Surely it's possible you could get a job?"

I swallowed hard and said in the most composed way I could: "You have a well-paid job, fighting for the likes of Great Bear N.V. and their hard cash. I have a job which is rewarded only by the knowledge that I'm defending real people with hard needs. It is a matter of debate who is more gainfully employed."

"Ah, well, yes," they said. "Good luck."

In their affidavit, the shadowy owners of the building (neither we nor the national media were able to meet them or find out who they really were), had said that they required immediate possession of the building due to plans to redevelop it as soon as possible. One and a half years after the occupants of Artillery Mansions were evicted from what for most was the only home they'd ever had, the three thousand room mansion on Victoria Street is still empty. The dignitaries chauffeured past its boarded up doors, include Messrs Major and Straw.

So when I hear John Major and Jack Straw say that beggars and winos are "eyesores" from which our streets must be reclaimed, it's all I can do not to wander 800 yards down the road from Artillery Mansions, in order to go one step further than yer man Guido Fawkes. For were we to blow the whole out-of-touch bag of hot air into the sky, they that do spout inside might land on the streets around them and finally learn something relevant to social politics. I did big time.

Related Articles

Rough Street Initiative 1 - two personal accounts of street-level attempts to help street homelessness - 1: Jerry Ham on MacNaghten House - Squall 11, Autumn 1995

Heavy Artillery - Squatters take Artillery Mansions - an 'in yer face' protest about homelessness in the heart of Westminster - Squall 6, Spring 1994

The Last Press Release - the eviction of Artillery Mansions occupation in Westminster on April 22nd (1994) - Squall 7, Summer 1994