International SQUALL

Bender Culture

Security for the pastoralists of Kenya comes through co-operation and mutual assistance. Tim Malyon visited the African tribes to see how it all works.

Squall 11, Autumn 1995, pg. 71.

The Samburu and Turkana tribes live a couple of hundred miles south of Lake Turkana, near northern Kenya’s Rift Valley where some of the earliest hominid fossils have been found. They’re nomadic pastoralists, herding goats, sheep, sometimes a few camels. Nomadic pastoralists came second in the evolving chain of human lifestyles - after hunter/gatherers but before settled agriculture, the industrial age, computer culture or DIY.

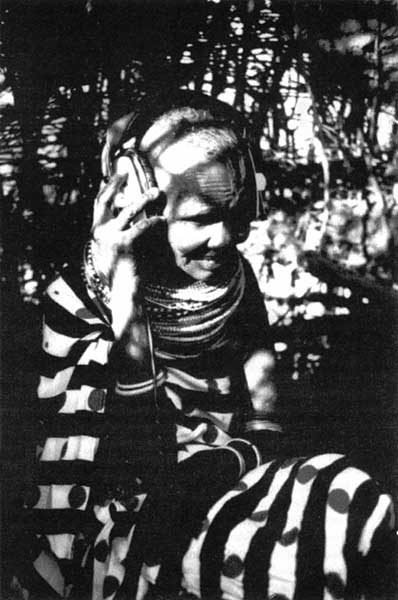

Enter Natiti village, beehive-shaped huts on a flat plain edged by distant hazy hills. The huts are made of saplings, both ends bent into the ground, covered in mud instead of tarpaulins. Akuwam Lochok is sitting in the bender’s shade. She’s a traditional vet. So’s Lokorio Modo, the old man sitting next to her. Akuwam begins, through a translator from the tribe: “We’re pure pastoralists. We only know about looking after animals. Nowadays most of us don’t have big herds, we have very few animals.

But we still stay with our old way of living. Only very recently we were raided and lost most of our animals.” The raids were carried out by neighbouring tribes and organised urban gangs enjoying political protection. They came on top of five years of drought, the longest in living memory, and drastic depletion of available land. Much of the less drought-prone, highland land, to which the Samburu and Turkana would migrate during the dry season is now fenced and used for growing grain, short-term profit in exchange for longer-term land erosion. Nomadic pastoralism has evolved as a uniquely sustainable lifestyle in this barren environment. But it depends on no land ownership and flexible land use so that different types of arid and semi-arid land can be used by different groups at suitable times of year.

The Samburu and Turkana’s attitude towards payment for services within the tribe is similar to their attitude towards land ownership - they find it foolish. Vets receive no payment, just thanks. The knowledge is “a gift from God,” according to Lokorio Modo: “Paying is not good. If I treat my friend or my brother’s animals, I don’t ask for anything, because I know that if I have a problem, if I loose my animals, then I can come to my brother and say, please, I need to use your animals.” Herds can be swiftly rebuilt, provided somebody has access to that drought-free land. What might seem idealistic to us is also a practical, reasoned survival strategy.

The Samburu and Turkana’s herbal veterinary system as well as human health care depends on plants locally available or collected from the nearby hills - DIY medicine. Again, the sharing of knowledge amongst Turkana and Samburu vets directly contradicts western ideas of ownership and patented drugs.

Jacob Wanyama is the programme vet for the Intermediate Technology Development Group (ITDG) who is working with traditional vets and also local schools so the knowledge is not lost. “If one person experiments and knows certain herbs but keeps quiet about it and doesn’t tell others, then he doesn’t help the community, and in the end he’ll be the only one to survive. But if the knowledge is shared, they all survive. When I first came here, I didn’t know how much knowledge these people possessed. But after working here for six years, I realised these people have more knowledge than a professional vet.” Wanyama adds that many of the highland medicinal plants and trees have been destroyed by grain growing operations, while lowland herbs have been devastated by drought.

Returning to Nairobi, there’s a Turkana woman selling her tribal beads on the street outside the airport. Shifting to the city sounds the death knell for many previously sustainable cultures. Since the rise of Babylon and settled agriculture, lifestyles have developed counterwise to the traditional ways of the Turkana and Samburu, away from cooperation and collective support, towards increasing competition. This leads to the pollution which is most likely responsible for abnormal droughts, and land-grab values which are depriving nomads throughout the world of the habitat they need to survive. These are ancient, specialist societies, whose wisdom is precious. It so happens that the return of the bender and the tipi to the west coincides with a radical reclaiming of the old values of cooperation and collective support - turning the tide or returning with the new wave? This time the crest feels sharper, the turn could be sweet.

ITDG and Oxfam are working with the Samburu and Turkana to re-establish a sustainable lifestyle in the face of drought and landloss. For further information write to ITDG Oxfam at:

Myson House Railway Terrace,

Rugby. CV21 3HT or:

274 Banbury Road,

Oxford, OX2 7DZ