Kraaking The System

Dutch squatters have their own brand of negotiation - and it works.

For this issue’s International section, SQUALL travels to Holland to look at their long-established squat (community) centres and speak with the free radicals. Sam Beale reports, Nick Cobbing shoots the pictures.

Squall 10, Summer 1995, pp. 40-41.

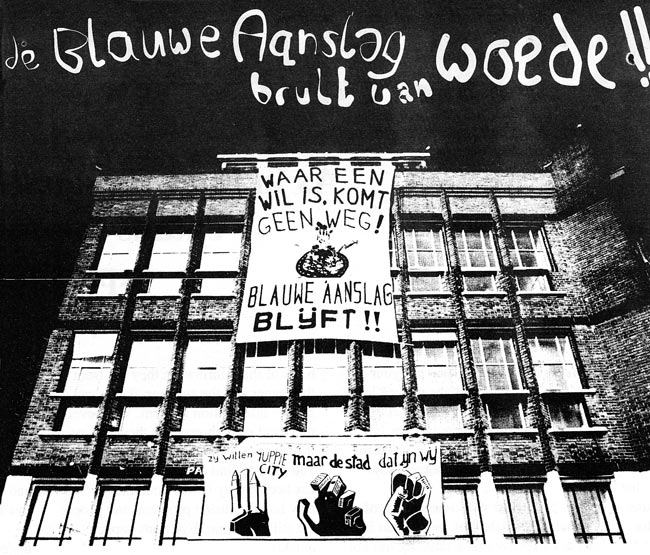

The most immediately striking thing about squatting in Holland is the age of some of the biggest and best-known squats: in Den Haag, in the south, the Blauwe Aanslag has been squatted since 1980; in Amsterdam, the Vrankryk and the Binnenpret since 1984. These buildings are vibrant examples of mature squatted communities. They have the sweet smell of long-term radicalism and dissent and have realised goals that squatters facing frequent evictions can only dream of. Hundreds of people around the country have either lived or worked in them, gone to their cafes and gigs or fought to defend them. They are a living squatting history, an inspiration to new squatters.

The Blauwe Aanslag is a massive squat in Den Haag, the Dutch seat of government and official royal residence. The building, once a tax office, was squatted in December 1980 and named the Blauwe Aanslag, the Blue Attack, because tax office correspondence is blue.

The squatters have built living spaces for over 50 people and at least 200 others regularly use the place. Locals are welcomed to the cafe and garden, created by the squatters from scratch. Mart, who has lived at the Blauwe for four years, believes community links are essential “we’re not making points about our house, we’re making points about the whole city.”

Since the building was first occupied the squatters have paid themselves a small rent, according to what each can afford, which pays for electricity and materials and funds actions. There is a venue in the basement, a cinema, workshops including a carpenters, a printshop (running as a small business for eleven years) a second-hand clothes shop, and a Kurdish library. Living spaces double as artists studios. Residents include artists, musicians, radio and film-makers, students and architects.

Five people work in the printshop earning “a bit more than on the dole,” says Jan, who lived at the Blauwe for 10 years and helped start the printshop. Kees, who has worked with him for five years, explained that in the beginning everyone worked voluntarily but due to a growing number of customers and pressure from the dole who “tried to find a job for us” they decided to “make the job here then!”. They are equipped with two presses, a dark room and a computer room. Jan explained that “you can support the groups you want to support by printing for them. It’s the main reason to keep on doing this: we can print at a cheaper rate for political groups.”

Support for political groups is a high priority. In the quiet, sunlit Kurdish library at the Blauwe, Turkish tea was served. Namdar explained that between 30 and 40 people a week use the library which serves as a meeting point for Kurdish and Turkish people. Namdar is one of four Kurdish men currently living at the Blauwe, building up support organisations for groups at home. Mart recalls police raids and arrests of Kurdish radicals in the building. It is another indication of the maturity of this squat that it has space, support and respect for this community.

By 1986 the Blauwe was sufficiently established to agree a four-stage plan with the city council. A fl1.5m (about £600,000) subsidy was promised to continue the work the squatters had begun and move towards legalisation. It seemed that the future of the building was assured.

Between ‘88 and ‘89 the city council began a massive redevelopment plan for Den Haag. “They want to make a gigantic techno-city, sky scrapers and all,” rants Martijn over the traffic noise, standing amidst the building site that is currently the city centre. It was finally revealed in 1992 that the council are planning to pedestrianise the centre and build a ring road around the city. The Blauwe Aanslag is in the path of this road.

The squatters have since campaigned to save the building and consolidated local support. They even produced two cheaper alternative schemes which would save the Blauwe. Both were rejected. One, designed by a group of architectural students living at the Blauwe, initially gained city-wide approval. “At the first city council meeting we had a lot of support and it looked like we were going to win. The next meeting was two months later and suddenly all the people who were for us turned against us,” remembers Mart. Ultimately this plan was refused because “the canal that runs alongside the building would have to be narrowed and they said the canal is of historical value. These hypocritical bastards have filled in most of the canals in Den Haag with sand and built on them already.” After this decision the ‘86 deal was forgotten, the road was to go ahead and the money promised to the Blauwe had disappeared down the Den Haag redevelopment blackhole.

On January 12th this year, at a council meeting which ultimately sealed the decision to evict, there was a massive demonstration which ended in violence when the squatters were told the meeting was full (it was obviously not). The police, recalls almost every squatter in Den Haag, took pleasure in taunting the demonstrators and the temperature rose to the point where the police charged, the crowd lost its collective rag and the council offices were attacked. Several people were seriously injured, six were arrested and charged.

Mascha, a long-time Den Haag squatter and activist explained that this violence, or rather the media blah that followed, led to an instant turnaround in attitude towards the Blauwe. She hopes that supporters have not abandoned the building because of this but it clearly hammered morale. She is working on building a case for those arrested on the January demo and, with a few others, has interviewed around 80 witnesses.

The Blauwe held a marathon two-day meeting in April to discuss what to do about the planned road. Opinion is divided. Some, like Jan in the print shop, feel there is a lot to lose from a no surrender position: “It is important for the city to have a place like this.” He recognises that it is difficult to move people and all the initiatives that have taken place to another building but thinks that, “politically speaking the chances that we could stay here are so little that between getting evicted and getting nothing instead or accepting another building from the city I think I would choose the last option”. Jan is not alone.

The Blauwe will get offered a deal and there are some who believe the community is more important than the building. Others cannot tolerate losing it, “not for more cars. That’s the stupidest reason you can think of,” says Den Haag squatter, Constantijn. Brigitte, who has worked in the printshop for two and half years, “fight to the death!’. Another local, fired right up by a visit to Claremont Road No-M11 Campaign last summer, thinks the occupants of the Blauwe should learn to defend the place Claremont-stylee. There is still a long way to go, the council’s plans could be two years coming but the meeting voted, in the first instance, to fight to the death.

In Amsterdam there is a lot of support for the Blauwe and this decision will be very popular. People drinking in the Vrankryk bar in the centre of the capital said they will to go to Den Haag and defend it. Some expressed a strong emotional link to the building, based on past battles, which they say they will never lose.

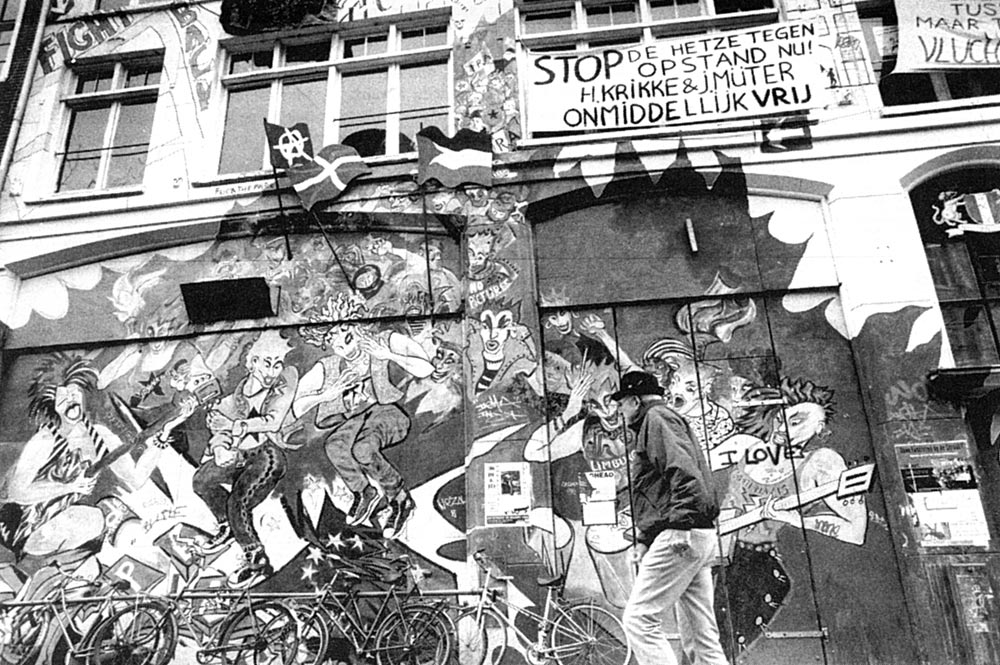

The Vrankryk is a loud, proud, brightly painted fortress. Squatted in 1984 it is known as a venue and centre of radicalism all over Holland. Paula, gay and lesbian activist amongst other things (including radical drag-queen and member of the Sissy Singers), has lived in the building for a year. He lived in a number of squats, including the Kolk, before moving to the Vrankryk which is currently home to around 18 people.

Downstairs is a venue and a classic squat cafe/bar which opens everyday from 10pm till 2am and later, when there is a gig. Paula explained the organisation of the building: “The venue is for everybody in the city.... we decided that it is better that not everybody who lived upstairs is involved downstairs, otherwise this house becomes like a central committee.”

Diversity is a key: “There are people living here who don’t come from the squatters’ movement, they come from the gay and lesbian movement, the antinuclear movement, any movement!” Everyone who lives in the house is political in some way. “That’s the first question we ask when somebody wants to live here, whether they are active in some kind of political way. We don’t really mind in what way.... well we do.... we don’t want party politics or 57 varieties of Trotskists.” Current activists include safe sex campaigners and people who find safe-houses for people on the run from psychiatric institutions.

Last year saw two major events at the Vrankryk. Firstly, the squat was married to an attractive, like-minded building over the road. Two huge gold rings hang in a tree in the street separating them as a reminder of the wedding ceremony which was “beautiful” remembers Paula. Secondly, they bought the building for fl250,000 (about £90,000, ie peanuts: the land is worth millions). Paula believes this was achieved because the building is so established: “The owner didn’t really know what was going on. When he found out how many people come here and do stuff I think he was a bit frightened.”

The Vrankryk has made extensive common-sense efforts to negotiate over the years with its neighbours. They have agreed only to have loud, late gigs once every few weeks, they close the bar at 2am and, said Paula, “tell people if they want to shout outside they can do it at home.” Such respect and practicality is an obvious aid in the negotiating process. “I can’t understand not giving the windows a paint job if they need it and it just makes sense to put your garbage out when everyone else does, not throw it in the garden. Freedom doesn’t consist of 'I can play my music as loud as I want to'.”

They raised the money to buy the place, partially from the bank. Similarly to the Blauwe, they now pay rent according to what they can afford. Someone on benefits pays about £100 a month, including electricity. If you earn you pay more, if you have nothing you pay nothing.

The squatters bought only the upstairs living space. Downstairs was ‘re-squatted’ and it will, of course, only be evicted if the current owners start proceedings. All events held in the venue are benefits for action groups. The space is also used for meetings, everything from anti-fascists to Queers in Space (a day cafe for gay and lesbian info and chats).

These big squats work, it seems, because they exist for, and ‘belong’ to, as many different groups as want to use them. The Binnenpret, 15 minutes cycle ride from the Vrankryk, is used by 13 different groups. Each is organised individually but remains part of the cooperative which meets regularly.

Following three years of negotiations, the Binnenpret was legalised last year. Meyndert, one of the building’s elder squatters, believes this was possible because, “the Binnenpret is a kind of octopus: because we have so many organisations we have a lot of different contacts everywhere in the city. We are grounded to the neighbourhood.” The building has rehearsal space for children’s theatre companies; a studio and rehearsal space for bands; a restaurant and coffee shop; an art studio; bicycle workshop; a venue and, of course, the stunningly chilled sauna which Squall spent a few hours in, for purely research purposes of course.

Sitting steaming in the Turkish Bath, waiting for a few oranges to be freshly squeezed for you, it takes an imaginative leap to picture a few nervous squatters breaking into this building one night 11 years ago. They took their chance to create this place where, whatever its legal status, there pervades a feeling that you are somewhere else, somewhere where physical and psychological well-being are a priority, somewhere far away from the expensive, tourist-trap ridden city centre just across the Vondelpark.

As the temperature in the bath rises and an ice cold dip, and perhaps another orange juice, are called for, a personal debate is forced for a visiting English squatter about what we actually want from squatting. In the first instance what we want is, presumably, affordable housing and a sense of community. Something else happens though; along with the on-the-edge, radical squatters life comes a taste for the on-the-edge, radical squatters life. At the Binnenpret and the Vrankryk there was no sense that negotiations have led to a compromise or change of direction for the squats. They do what they want to do and learn to work neighbourhood structures; a key to legalisation or buying your squat. It is clear that this process does not water down radicalism, it strengthens communities, gives them security and allows people to plan and achieve long-term projects.

Legalisation or negotiating is no longer a straightforward process in Holland and it does not guarantee permanent stability (as the current situation at the Blauwe clearly demonstrates) which is why more squatters are attempting to buy their buildings. The more local support a squat has and the more impressive working initiatives, the more chance it has of achieving and retaining legalised status.

In this country local authorities do not have nearly as much practice at negotiating with squatters. They don’t like to do it and it is down to squatters to push for negotiations. Pushing means creating something to bargain with, building local support, achieving goals. Past experiences of hard work and big plans dashed by impenetrable prejudice against squatters by local authorities and property owners is naturally less than inspirational for squatters contemplating negotiations. Nonetheless directives on community initiatives for local authorities, like Agenda 21 which came out of the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, are, regardless of their enforceability or substance, places to make the push.

By gaining legitimacy these Dutch squatters have won game, set and match. They started off as stigmatised as any squatters and through clear vision, common sense and hard work they’ve turned it around so that their local authorities have effectively sanctioned squatting as a valid way of people taking control of their housing and community needs.

Related Articles

Read the other articles from Squall's report back on squatting in Holland in Squall 10:

What's The Kraak / Kraaking Info

They Must Be Krakers - Battle zone as Kalenderpanden - the large community squat in Amsterdam - is evicted - 18-Nov-2000