Unthinkable Thoughts

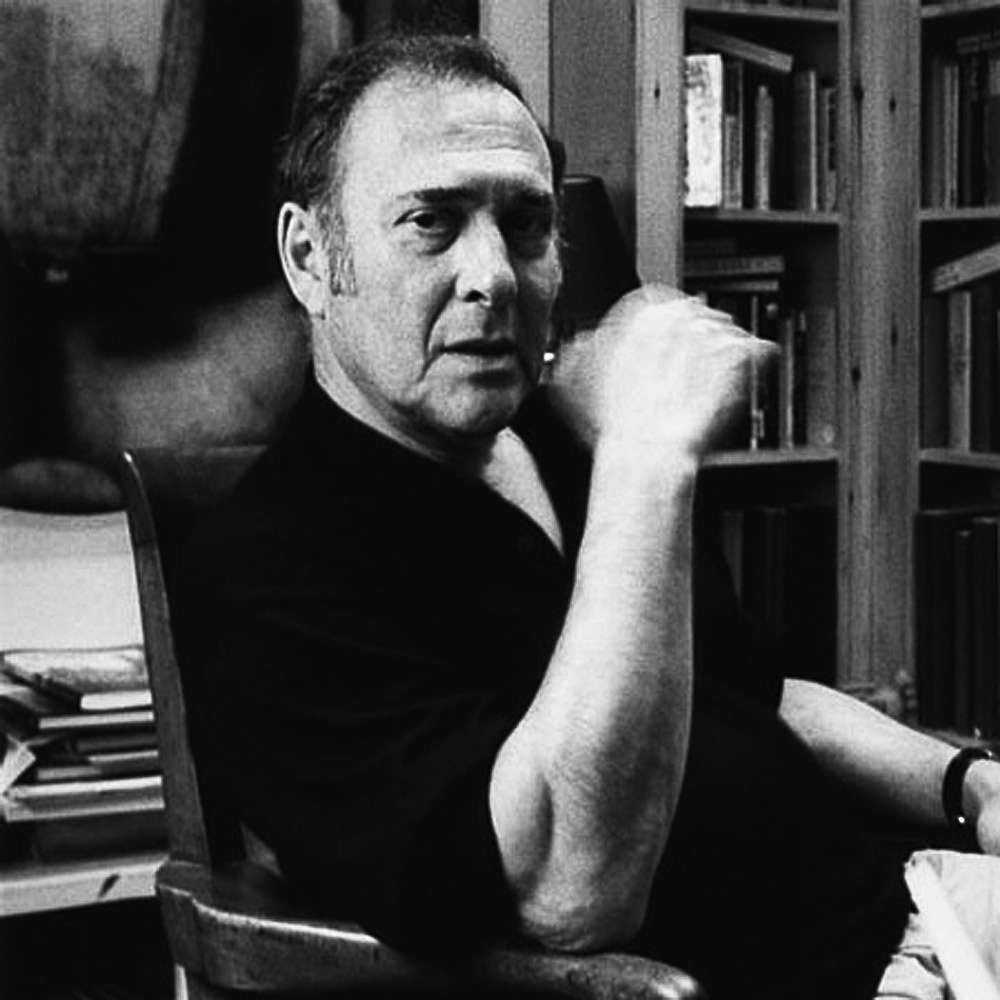

Interview with Harold Pinter

Harold Pinter is one of the UK's most esteemed theatre and screen writers and one of the few artists of his stature prepared to speak out on matters of socio-political importance. David Edwards caught up with one of this country's literary greats, to gauge his thoughts on western politics and why the mainstream media attempt to ostracise him as just an angry old man.

2000

"There was a time, by the way," Harold Pinter confided to the Confederation of Analytical Psychologists in June, "when I thought Tony Blair would do well to consult one, or even two, of you ladies and gentlemen here tonight. I was struck by the demented light of battle in his eyes. But now I'm not at all sure that he's actually gone round the bend. I've come to the conclusion that his moral fervour and fanaticism is a masquerade."

There is no record of how the audience of Jungian therapists reacted to a potential patient being described as "round the bend" but anyway there were more pressing issues at hand: the subject of Pinter's talk was 'The NATO action in Serbia', or more to the point: 'Why NATO's action in Serbia?' This is Pinter's conclusion:

"The answer appears to lie in the considerable potential oil wealth in the Caspian Sea region."

Readers will immediately notice that this is a million miles from the mainstream media and political consensus that NATO's action was motivated by the desire to "avert a humanitarian catastrophe". One Guardian journalist ridiculed the idea that oil might have been a consideration in NATO's thinking: "How absurd it is to refer to the oil in the Caspian Sea region as having anything to do with the NATO operation. The Caspian Sea is over a thousand miles from Yugoslavia." (Jonathan Freedland)

"It is indeed," Pinter responds, "But to get the oil from the Caspian Sea into the hands of the West you can't use buckets. You need pipelines and those pipelines have to be installed and protected. The oil reserves in the Caspian Sea are vast. The pipelines mean that security in the Balkans is of concrete economic and strategic importance."

Interviewed at the time, Pinter said: ""The NATO war is a bandit action, committed with no serious consideration of the consequences, confused, ill thought, miscalculated, an act of deplorable machismo ...... How do you achieve moral authority ? You don't. You don't have to bother. What you have is power. Bombs and power. And that's your moral authority.... Tony Blair is leading us in a sanctimonious crusade that bestows a sheen of moral purpose but is fundamentally hollow.

I asked him how the psychotherapists had received his version of events:

PINTER: Oh it was quite a night, it really was. It was a very interesting evening because it was packed, you know - they were all Jungian psychotherapists - and I gave my speech and then, really, all hell broke loose!

EDWARDS: In what way?

PINTER: Well what actually happened was there were a lot of pretty traditional male psychiatrists - to be a psychiatrist doesn't mean you're a radical person, you can be anything really - but there was also a whole body of Serbian female psychotherapists who practice here in England. And between these two groups there were really tremendous clashes that became very passionate, and violent really.

EDWARDS: Violent!

PINTER: They didn't actually come to blows, but it was very very intense.

EDWARDS: They weren't managing their anger too well?

PINTER: They certainly weren't, they were really letting it out, I'll tell you. So it was quite a night.

EDWARDS: How did the Serbian women react to what you said?

PINTER: Well, the Serbian women were very much with me, you know. I was under attack myself from the other lot who simply parroted the same old clichés: 'Genocide, you've got to do something about it' and all that.

EDWARDS: It's amazing how well all that has worked to stifle debate isn't it...?

PINTER: Yeah, shocking.

EDWARDS: You know, 'We had to do something, there's a genocide going on', when in fact 2,000 people had been killed on all sides in the twelve months before the bombing began...

PINTER: That's absolutely right. When they said 'We had to do something', I said 'Who is this 'we' exactly that you're talking about? First of all: Who is the 'we'? Under what heading do 'we' act, under what law? And also, the notion that this 'we' has the right to act,' I said, 'presupposes a moral authority of which this 'we' possesses not a jot! It doesn't exist!'

EDWARDS: And also in terms of the 'we', NATO is answerable to no democratic constituency, Jamie Shea [NATO spokesman] didn't represent anyone.

PINTER: Absolutely. This was all, as everyone I think really knows, totally illegitimate, totally illegal, totally immoral, and in fact criminal. The Serbian women were very impressive actually, they really knew what they were talking about. They poured scorn on a whole lot of received ideas and fabrications and lies that the male psychiatrists were just repeating, you know, what they had read in the papers. And of course the Serbian women also knew their history, which is a damn sight more than we do over here. So that was that. So I'm very glad I did it. UNTHINKABLE THOUGHT NO.1 - FREE PRESS OR CORPORATE PRESS?

EDWARDS: What I thought would be interesting - we can talk more about the Serbian issue later - I thought the title of this could be something like 'Unthinkable Thoughts'. It seems to me that there are a number of big unthinkable thoughts that almost never make it into the mainstream. In a sense I think the mainstream can't deal with these ideas, so they have to be filtered out. The first one is the idea that the corporate press isn't a free press. It seems to me that the idea that we've got a free press is in fact an illusion - this applies to the mass media generally - what we've got is a corporate press, a corporate mass media, that's not the same thing.

PINTER: You know there's a great story in Nick Cohen's book 'Cruel Britannia' about Monsanto and the GM issue. Two reporters for a television company in the States came across what's really going on with GM foods and they said 'We've got to pursue this and we've got to do a programme on it', and they got gently nudged aside - it wasn't an outright 'no!', but it was just 'No I don't think so, it's not proved', and so on, and they were just nudged out of the whole thing until they got very very irritated and said 'We've got to do this, it's the responsibility of the company to do it.' And, finally, the head guy said 'Listen, what is news is what we say it is! That's it! And for us that's not news, right!' And then they were fired! So, 'What is news is just what we say it is', is finally - they try not to say such a thing - but when finally pushed, that is the bottom line.

EDWARDS: Have you come across anything like that in your own experience? Some of your stuff is really outrageous by mainstream standards but it gets in - it's very unusual for this sort of stuff to get in isn't it?

PINTER: It is, it is. I've never actually been censored in that respect, apart from my poem American Football, which I regard as an act of censorship at the time - during the Gulf War - without any question. Apart from that I haven't. The way they deal with me is in another way. I'll give you two examples. One was when I wrote that 'Open Letter to the Prime Minister', Mr Blair. As you know The Guardian published it, but when I picked up The Guardian the next day and opened the paper, there I read - instead of 'Open Letter to the Prime Minister' - 'Writer Outraged'!

EDWARDS: What did you interpret that as signifying?

PINTER: Well I'll tell you exactly. It meant 'Some idiot of a writer is outraged. This guy's always outraged. He's not like your local milkman or the bus driver: he's a writer - these writers - you can't trust them an inch, he's always outraged'. So I phoned the bloke, David Leigh actually, the editor of that page, and I said 'Why did you call it 'Writer Outraged'? And he said 'Well aren't you outraged?'. I said, you know, 'That's not the point', I said... because the tone of the article was of considerable irony and mockery, on my part - there was no outrage, leave the outrage aside. My indignation and contempt are implicit in the article, but I was just being really quite light about the whole thing, the whole tone of voice was quite light and ironic. So to call it 'Writer Outraged' means you don't have to read it. And I'll give you one other example which I really think is significant in this context. A couple of years ago The Observer - which I've given up by the way, after thirty-five, forty years: to hell with it! I'll come back to that - a couple of years ago The Observer had a front page about a Kurdish deserter from the PKK who they said had blown the gaff on the fact that the PKK were going to poison the whole world, they'd got all this poison. This is front page news! So I wrote a letter saying 'Who is this guy? What is your evidence? What are you talking about? Do you know the real facts about the Turkish-Kurdish situation? Just explain yourself'. And my letter went in. But do you know what they called it? They put a little title: 'A Playwright Rants'. You see, so it's consistent. [On May 16 1999, Jay Rayner wrote an article in The Observer entitled 'Pinter of Discontent'. The subtitles below read: "Hated Pinochet; loathed Thatcher; doesn't like America; deplores NATO; is disgusted when his play doesn't get a West End run. Good old Harold - he's always bitching about something." Rayner referred to Pinter's obsessive "bitching" nearly thirty times, using language like: "raging", "sound and fury", "growling", "outraged", "attacking", "hostility", "rowing", "ever ready to pick a fight", "yelling", "barracking", "fury" (again), "raging" (again).]

EDWARDS: Did you see something by Jay Rayner a couple of months ago...?

PINTER: That was it. That's why I finally gave up The Observer. I gave it up after that.

EDWARDS: I read that, I was amazed by that. It was very much, you know 'You need people like Harold Pinter because he's always outraged about something and it's sort of quite amusing but...'

PINTER: It said that all I do is shout in that profile: 'He just shouts about everything', you know. That is another way of undermining anyone who insists on maintaining a serious political position. One of the things which was included in my "shouting" was my television programme about NATO. The implication was that any attack on the NATO bombing must be irrational. PAUSE FOR THOUGHT NO.2 - DERIDING DISSENT

EDWARDS: The other thing you get of course is 'Sorry, this guy's a playwright, what the hell is he doing commenting on politics?'

PINTER: Yes.

EDWARDS: What's interesting about that is that Chomsky, again, has had exactly the same thing. For a long time they were saying 'Sorry, you're a professor of linguistics, what authority have you got to talk about politics?' And he said 'Well, I'm a human being'. And this is arguably the world's greatest critic of US politics, foreign policy and so on. It's as if there were some sort of profession, 'Social Critic', and only if you pass some kind of exam can you be a social critic. It's very bizarre. You get that as well don't you: 'What's this outraged thespian doing talking about the bombing of Serbia?'

PINTER: That's right, but there is another side to the coin. You know the 'Counterblast' television programme I did [BBC2 4.5.99] It was the only programme on the whole of British television during the whole period which was against the war, which analysed the situation and question critically. The BBC did it, they had no alternative - the hierarchy had to let it happen, there was no interference - but three things happened that were of great significance I thought. The first thing was they didn't publicise it at all - nothing! - you wouldn't have known it was on except by accident...and the press - they ignored it.

EDWARDS: That's right, it wasn't reviewed in The Guardian was it. Was it reviewed anywhere?

PINTER: No, the only fellow who reviewed it was Timothy Garton-Ash in the Independent ['Vivid, dark, powerful and magnificent - but wrong', 6.5.99], and he wrote an article which was finally an attack on it, but nevertheless it was a response.

EDWARDS: Did he say you were outraged?

PINTER: No, no, he was alright... But apart from that there was nothing. But what did happen - the other side of the coin I mentioned - was that I received more letters from the people in this country about that programme than I have ever received in my life about anything.

EDWARDS: How many?

PINTER: Well about 350-400 letters. There were, I would say, ten who called me a real, you know, pain in the arse, and the rest, the rest, were really very moving letters because they demonstrated the depth of shame of people in this country - I can't tell you - and anger, and impotence, and frustration. An extraordinary proportion of them just resigned from the Labour Party. So I was very struck by that, and it told me that underneath what we're saying about how the media is controlled and so on, there are people living in this country, you know, who actually hated what was going on.

EDWARDS: And of course the media always give the impression that people are completely indifferent to everything that's going on and couldn't care less...

PINTER: That is actually bollocks.

EDWARDS: It is bollocks isn't it. I felt an incredible sense of... I just sat there night after night, I couldn't believe it was happening, just laying waste to this country night after night - power stations, bridges, TV stations, hospitals - it was just so murderous and you felt so impotent.

PINTER: I'm happy that I can speak and that I do speak.

EDWARDS: I think it's incredibly important that at least one or two people actually get heard, because it does create a sort of sense of hope. Just the fact that your programme was there, or your letter, or Pilger's, because it helps people think 'Christ it's not just me thinking that, I'm not alone.'

PINTER: That is absolutely the case. That was very much the nature of the letters that I got. The sense of being totally lonely, you know. UNTHINKABLE THOUGHT NO.2 - PROFITABLE DICTATORSHIPS

EDWARDS: The second unthinkable thought I'd like to discuss with you is this: Not only does the West not promote democracy around the world, it is utterly dependent on dictators to protect "good investment climates" from local nationalists to serve Western corporations. Do you agree with that?

PINTER: I do. I think that, um, this has always been the case. The term dictator, I suppose, now has to be looked at in a slightly different way. There are very few obvious dictators as such knocking around, you know, these days. But something else has happened. I'm very very interested, for example, in the case of Haiti, which seems to me immediately a case in point. Haiti's a place that most people don't give a damn about, you know. But the fact is that the case of Haiti represents one of the most appalling examples of US manipulation and power that the world has ever seen. Not many people know that the US - capitalism in the guise of the US - supported the most appalling dictators in Haiti, the Duvaliers, for years and years and years. And finally, when, to cut a long story short, the Haitian people became so exhausted and fed up with the whole bloody thing, the US said 'Too many people have been tortured and killed, we'd better withdraw our support, just a bit, and see what happens'. And so then they actually had democratic elections and Aristide was elected - 67 percent voted for him - the US said, 'What! This is an actual democratic election! The man is actually democratically elected! Wait a minute!'...

EDWARDS: It's not supposed to work like that!

PINTER: So they bided their time, if you'll recall, and in 1991 - he had eight months - and he was concerned with actually doing something about the country and about the people who live in the country, you know, and not submitting to the neoliberal strategy and the whole bloody total financial and economic manipulation. So of course what happens: a military coup, bang! He's out. Aristide escapes to America: they ostensibly gave him sanctuary, but they'd actually brought about the coup themselves; the CIA in league with the military brought it about! So then they get him over there and they try to hammer into him his actual responsibilities to them, or to capitalism. Meanwhile the military are killing at least 3,000 people, the most brutal three years, and the US says 'Now we're going to pretend to be the good guys.' So they go and invade Haiti under the United Nations' auspices and they ostensibly set up a democratic state - this is 'Saving the world for democracy'! What they're actually saying is that the only way to get this country off the ground is a neoliberal strategy in which the market runs everything... etc, etc. And now the poverty line in Haiti is worse than it's ever been, absolutely appalling, the country's sort of devastated. Now I come back to the term dictator: there isn't a dictator as such standing there as there was in Haiti, at the moment, but there's an elite, and this elite is extremely rich, most of the members are businessmen, and that's it: the new dictatorship seems to me to be a business dictatorship.

EDWARDS: Is this part of the idea that it's not good for tourism, it's not good for investment, to be seen to have a dictatorship? Say in Argentina or Chile: Pinochet takes a back seat, in fact he was still in power, or at least the army was.

PINTER: The army's right there. Tanks are just around the corner.

EDWARDS: It seems to me that there are some very basic psychological tricks being played on us. One trick is, 'We have to do something, there's a genocide', so that any sane person sits there thinking 'Well of course we can't sit back, it's like the holocaust, we've got to do something.' And then Tony Blair says, in response to the charge of hypocrisy - he said it on the BBC's Question Time - 'I'm sorry, but just because we can't help everybody doesn't mean we shouldn't help the people we can help'. But of course if you look at Iraq where 800,000 children have died as a result of Western sanctions, at Cuba where children with cancer can't get anti-sickness drugs because of sanctions and are vomiting 28 times a day, when Blair says we can't help those people, what he actually has to be taken to mean is 'We can't lift our boots from their necks', because that's what helping them would actually mean isn't it?

PINTER: I think that's very well said. I absolutely agree.

EDWARDS: But he's able to get away with that trick isn't he?: 'You could call it hypocrisy, but you could argue instead that we're doing what we can do', which is a total distortion of reality.

PINTER: It really is indeed nauseating. It really becomes very difficult to find words strong enough...

EDWARDS: Don't you think the gap between reality and the depiction of reality becomes so huge that you almost can't bridge it without looking absurd? It's a real problem isn't it?

PINTER: I know what you mean, yes. I've always said finally one thing: 'My political writing is entirely to do with facts. I make absolutely nothing up '.

EDWARDS: Often quoting from state documents.

PINTER: Absolutely. There's a lot been released on the Internet recently. The one thing the US has is this Freedom of Information Act - it's not very good really because they black almost everything out, but they can't black everything out - you have to give them that: they've got it, it's there, so it can be used, whereas here, as you know, the whole thing is a farce, it's disgraceful. But at least they've got something there and a while ago I got state documents about the CIA, about the US government involvement in the military coup in Chile. It's all there! So What Are The Other Writers Doing?

EDWARDS: There it all is! This is what amazes me. Shortly before his execution at the hands of the Nigerian regime, Ken Saro-Wiwa said: "In this country [Britain] writers write to entertain, they raise questions of individual existence - you know the angst of the individual - but for a Nigerian writer in my position you can't go into that... You cannot have art for art's sake. This art must do something to transform the lives of a community, of a nation. And for that reason, literature has a different purpose altogether in that sort of society, completely different from here." (Ken Saro-Wiwa, the Independent, 14.11.95) Which raises the question: what are the other writers doing? There's you, there's Pilger, there's Mark Curtis, Paul Foot, say, there's maybe Greg Palast, you know, Nick Cohen. How do you explain the fact that so few people are willing to actually say these things? Obvious truths - you don't have to make anything up - you just get the state documents, you get the facts, the logic is very very simple, very obvious, and yet nobody's saying it. How can that be?

PINTER: Well, you know...

EDWARDS: Or do you know a lot of people who do know but won't talk about it? You must meet other playwrights, novelists, writers all the time...

PINTER: I don't.

EDWARDS: You don't?

PINTER: No, I don't meet them. Well, one or two.

EDWARDS: That's a misapprehension then.

PINTER: Yes. Well, people at a summer school in Cambridge, people from all over the world, everywhere really, asked me a number of very interesting questions a while back. One of the questions was 'What are the other writers in this country doing in relation to the NATO bombing? The other playwrights, the other novelists, and so on?', you know. Firstly, I said 'I don't know'.

EDWARDS: You don't know.

PINTER: Well, that's what I said first. I then thought about it and I said two things. One is that the young writers - there are a lot of very lively, young playwrights these days, you know - but it seems that they're silent on the whole question of 'What's going on'. It's possible to say that they share a fundamental cynicism about the world...

EDWARDS: That nothing can be done.

PINTER: Yeah, so they don't give a shit. 'It's the world', 'That's the world: do what you bloody like with the world, we've lost interest'. That may be the case, I'm offering tentative...

EDWARDS: Can I just refer back to, you know, we were saying about how the mainstream really tries hard to give the impression that everything's hopeless, that there can be no change. It's a very powerful psychological weapon to stop people caring isn't it?

PINTER: That is absolutely right.... There's another thing you've got to take on board: that a lot of intelligent people, who can't miss what's happening in this bloody world, just like being part of the establishment.

EDWARDS: For the rewards?

PINTER: And for the status, I suppose. And the fact that they're loved, embraced.

EDWARDS: Loved?

PINTER: Well, embraced.

EDWARDS: Do you think it's... normally I would say it's cynical stuff like money and power and prestige. Are you saying it's because they need to sort of belong somewhere?

PINTER: I think it's possible. As I say, this is not a scientific investigation, these are just propositions.

EDWARDS: So what happens when you do what you do? Do you become a complete outsider?

PINTER: Well, I'm in an odd position because in a sense I'm undoubtedly an outsider in society because I simply use my critical intelligence...

EDWARDS: Which not many people do.

PINTER: But at the same time, I have to face the fact - it's not a bad thing - that I'm very much part of the world in which I live because I've been part of it for such a long time and I've done an awful lot of work and my work is performed, and done, and I'm part of all that. So that I think I'm also accepted generally as an idiosyncratic, you know, bloke, who nevertheless is part of contemporary drama - my plays have been done for the last 45 years or whatever it is.

EDWARDS: So you get your sense of belonging from that. But do you feel politically lonely?

PINTER: I have gone through very very lonely patches, yes. There are various places, other countries, where I feel much more at home: Italy, Greece, and Spain. I mean 95% of the Greek people were against the bombing, 95%! Same with Italy, they hated the whole bloody thing. But even there the government had to go with it. This is the real horror of US power.

EDWARDS: So what you're saying then - and it's not scientific - is that what stops people saying this stuff, is not simply crude things like they want money and status, it's the psychological pain you have to suffer when you make yourself an outsider by challenging what cannot be challenged if the system is to function smoothly. If you say things like 'We haven't got a free press', if you say 'We have to support dictators to protect our profits', you thereby make yourself an outsider from the smooth functioning of the system and, psychologically, it's hugely painful to be an outsider.

PINTER: Yes. I think it's a question of securing your uneasy and precarious place in the world: the best thing to do is not ask too many questions. You remember Mohammed Ali was drafted into the army and he made his famous statement [Affects American accent]: "I ain't got no quarrel with them Vietcong!" That's what he said and that got him into so much trouble!... Jesus!... what they tried to do to him! He's a remarkable fellow. So I think that with some people there's a terrible fear of being unpopular, but somehow I've always been vaguely unpopular, so I'm used to it.

Related Articles

Art, Truth And Politics - Harold Pinter with sharp diagnosis on art, media and US politics - 08-Dec-2005

Links