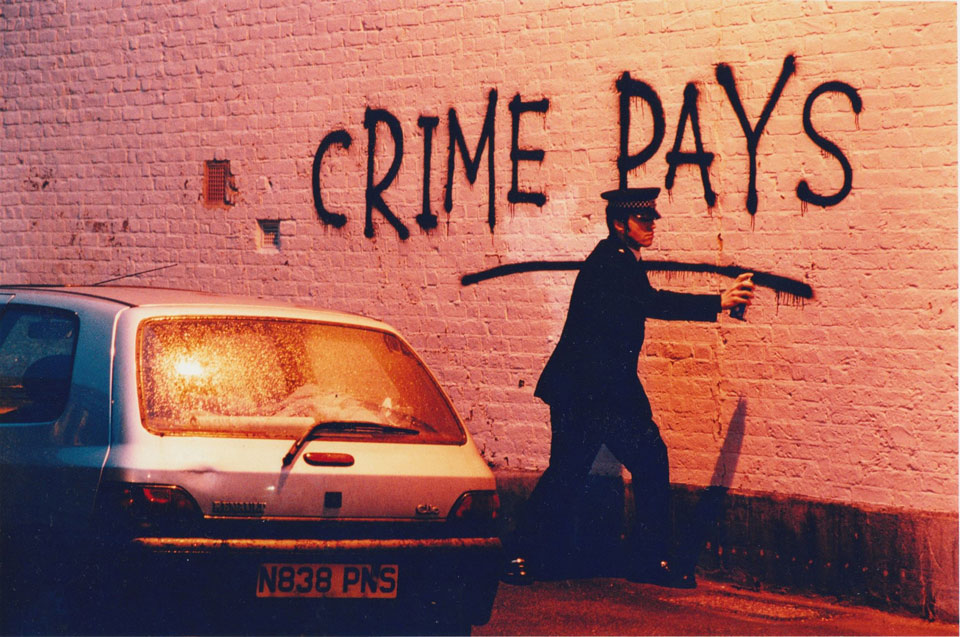

Cashing In The Coppers

Investigation into creeping privatisation of British police force

As more and more policing duties pass over to the corporate security industry, Si Mitchell investigates the escalating involvement of private finance in British policing.

2001

In the early 1990's one of Britain's first forays into private policing collapsed farcically. Residents had agreed to pay Andrew Burke and his firm, SAS, to patrol the leafy streets of Bristol's affluent Sneyd Park estate. Embarrassment followed when Burke began distributing photographs of local youths he'd personally decided were up to no good. Not long after, Burke was arrested for assaulting a young man in the line of his duty and the experiment ended. Before long the Tory road-building programme would be dogged with daily tales of private security guards working for Group 4 or Reliance, fresh out of jail and after a half days training, beating environmental protesters at the M11 link road or the Newbury bypass. On the PR front the security industry needed a serious respin. But it would take more than bad press to keep private cash out of the law and order business. Sponsorship of police cars followed. 'Threshers say don't drink and drive' was the slogan adopted by Avon and Somerset police on their squad cars before the insurance company, Hill House Hammond took over logo-residency on the force's car doors. Sponsorship then extended to websites, helicopters and eventually beat officers.

Never reluctant to put themselves about, Avon and Somerset were the first force to accept sponsorship for a constable (from radar company, Racal) and have recently taken an undisclosed amount of money from Barclaycard to pay for a specialist officer working on credit card crime. Going one step further, Devon and Cornwall police now regularly rent out their officers to private companies (£310 a day for a constable, £365 for a chief inspector) whilst the Royal Devon and Cornwall Hospital in Exeter pays £60,000 a year for two dedicated officers. "It's more effective than private security companies because [with them] you only get two men and a van," said a police spokesman, as if touting for trade. "But if our officers come across something that needs dogs, the helicopter or additional back-up, the full force is there for them."

Liverpool City Council has hired 20 mounted officers to patrol the city's parks and shopping centres a scheme which has swallowed half of the council's £1 million pound public safety programme for the coming year. Back in Bristol retailers in the Broadmead shopping precinct are trying to club together £90,000 for three dedicated police constables. Making sure everyone understands the role of the shop-cops, centre manager John Hirst said: "I'm not prepared to have begging in my centre. People will have to do it somewhere else."

"The beat bobby is dead, long live Securicop." - Police Magazine.

Fred Broughton, chair of the Police Federation, is unimpressed: "The principle of private individuals and businesses paying for policing is fundamentally wrong. Law enforcement should be available to all."

However, private security patrols have returned to wealthy Sneyd Park. But now they're called 'wardens', and it is the police which are offering to broker the deal and train the staff. Already 450 residents have said they'd pay the extra £1.50-a-week for the scheme (a fifty pence increase on Andrew Burke's original fee).

In April Tony Blair awarded £50 million to be used for street warden schemes, saying: "Often the best way to improve an area is to raise the presence and profile of local public officials." The Street wardens will join nearly five hundred Neighbourhood Wardens funded under the Department of Transport, Local Government and the Regions (DTLR) via New Deal for Communities and the Single Regeneration Budget.

ACPO and the Police Federation are in favour of wardens (or "super caretakers" as Blair likes to call them) as long as they are just "the eyes and ears of the community". For community, read police and local authority. Tasked with reporting graffiti and noise pollution, they can (at the discretion of their employer) be given powers to spot-fine people for offences such as dog fouling. A partnership of local authority, police and community associations will employ the wardens. The scheme represents a further creep of private involvement in law enforcement.

When traffic wardens were first introduced it was stressed they would have no police powers. Last month Home Office officials and police chiefs were discussing a document which will form the basis of David Blunkett's police reform bill. It proposes giving traffic wardens powers to deal with 19 new categories of criminal offence. The paper also proposes giving the new street wardens the power of detention and using them to monitor juvenile curfews, sex offenders and other potentially violent offenders. It suggests the creation of "a middle tier of policing, possibly called police auxiliaries".

The Private Security Industry Act (PSI), which received Royal Assent in May will set up a Security Industry Authority (SIA) responsible for licencing each guard after considering their criminal history - and possibly their training. A voluntary Approved Contractor scheme will award participating firms with a government approved logo.

The idea was first launched by Surrey chief constable, Ian Blair, in 1998. His 'kite marked' patrol concept was designed to maintain a non-police "uniformed presence on the streets" but was met with scathing criticism at the time. "The beat Bobby is dead, long live Securicop," wrote the Police Federation's Police magazine. "If the public can't have the full PC Monty, they might get an ersatz version - under-powered and underpaid."

"Police regulation provides us with real opportunity to develop partnerships with the private sector." - Richard Childs, Chief Constable of Lincolnshire.

The 2001 PSI Act aims to "reduce crime and the fear of crime by removing, and being seen to remove, criminal elements" from within Britain's estimated 137,000 strong private security workforce (the police employ 124,500). The public are being groomed to accept private security guards as legitimate authority.

In May the Joint Security Industry Council (JSIC) held its second annual forum at the Queen Elizabeth Conference Centre in London. Then Home Office minister, and now Labour party chairman and cabinet minister-without-portfolio, Charles Clarke, was scheduled to give the keynote address. His presence would have lent considerable weight to a body hoping to establish itself as the "independent voice of the private security industry" in "discussions" with government over the make up of the SIA. Clarke couldn't make it due to election commitments, but the JSIC are still well placed. Their president, Lord Mackenzie of Framwellgate, the former chief superintendent of Durham constabulary and former president of the Police Superintendents Association, is a police adviser to the Home Secretary. The top echelons of the police, like government, are keen to get private patrols out on the streets. Richard Childs, chief constable of Lincolnshire and chairman of ACPO Crime Prevention Initiatives told the gathered security elite of the JSIC of "the opportunities" present by the PSI Act, and how the industry could lighten the police load in fighting "low-level crime". He told them to look at providing services "in areas where public funding doesn't exist and won't exist again".

"For the police," he said, "regulation provides us with real opportunity to develop partnerships with the private sector".

The revolving door between police service and private security industry is already spinning at some rate. One of the industry's most vocal advocates is ex-West Midlands chief constable and former HM Inspector of Constabulary, Geoffrey Dear. A fervent public advocate for more corporate involvement in policing, Dear is now a director on the board of Reliance security.

"[The scheme frees up a] three way exchange of information between police, the private security firm and the local authority or business."

- Local authority missive.

During the mammoth McLibel trial the vice president of McDonald's UK, Sid Nicholson, himself a fomer police officer, admitted that all McDonald's security department were ex-policeman his company had easy access to confidential information held on the police's database.

"If I wanted to know something about someone," he told the High Court, "I would make contact with the local crimes beat officer, the local CID officer, the local collator." This three way exchange of information between the police and a corporate security department - and the private investigation firm hired by McDonald's to infiltrate the activist groups they were targeting - resulted in the Met paying a £10,000 out of court settlement and making an embarrassing public apology.

Similarly, Reliance security admitted receiving information from Special Branch on anti-roads protesters at the M11 link and Batheaston bypass and went on to have staff prosecuted for assault, and to be heavily criticised for their policing methods in general. And yet this is exactly the sort of partnership, ACPO and the government are hoping to generate with their newly accredited security industry.

Last year Telford Council employed Bob King's Business Watch Guarding to patrol 85 schools and some other public buildings as part of their Schools Watch programme. King, another ex-copper, set up the company after quitting West Mercia police with a back injury. According to the local authority the scheme frees up police resources and cuts crime with a "three way exchange of information between police, the private security firm and the local authority or business".

"PFI moves policing further from public scrutiny and increases the private sector's stake in shaping criminal justice policy.."

- Stephen Nathan.

Editor of Prison Privatisation Report International When Lancashire police agreed to spend £450,000 over the next three years on private security firms to guard their police stations, Gordon Prentice, Labour MP for Prendle, asked Home Office minister Paul Boateng: "Where are the criminals who want to break into police headquarters staffed by police 24 hours a day, 365 days a year?" Needless to say he didn't get a proper reply for that or his next question: "Will Group 4 be guarding the soldiers at Preston barracks?"

However, the project that Sussex Police Authority have described as their "most wide reaching" PFI scheme, puts private security guards directly into a policing role. In January Reliance Custodial Services sealed a £90 million deal to provide custody services for the entire Sussex region. Six privately managed custody centres will replace 24 existing police stations. Despite boasting former HM Inspector of Constabulary, Geoffrey Dear, as a director, Reliance's track record in police service provision is not good. A 15 man pilot project in West Mercia suffered what was described as "teething troubles" and a five year contract to operate a tagging scheme in southern England was terminated not long after it started. Dear's friends at Sussex Police Authority describe Reliance as "a market leader in police support services". Graham Alexander of Sussex's regional Police Federation claims the reduction in police stations will increase journey times, meaning less police time on the streets: "If it's a cost cutting exercise it's fraught with danger."

Yet the project is unlikely even to save much public money. The Government is already subsidising the scheme to the tune of £34m. In November, Sarah O'Connor of Sussex Police Authority told Stephen Nathan editor of Prison Privatisation Report International: "We are in the bottom quarter [of Home Office figures] for arrests per 100 officers. We have to increase arrests by 53 per cent."

Payment to Reliance will be linked to the rate of prisoner turnover - more arrests equals more money. Nathan's concerns are that PFI schemes bear no relation to the needs of the community. "PFI moves policing further from public scrutiny and increases the private sector's stake in shaping criminal justice policy," he told SQUALL. "If the police fail to meet their targets, will staffing levels be cut to protect profits?"

Or, indeed, will people be arrested to make up the shortfall? "The scheme is shrouded in commercial confidentiality," he continues, "yet there are fundamental issues such as monitoring of custody procedures, as a single monitor is proposed for all six centres. What is worrying is that other police authorities are looking to Sussex as a model for further schemes."

"A justice system should be directly accountable to the people not to company shareholders."

- Mike Schwartz, Lawyer.

In July Staffordshire police announced a contract where Premier Prisons will provide civilian detention officers in the Chase division. Premier holds the most private prison and monitoring contracts in the UK and rose to fame in the UK in 1998 by chaining a pregnant woman to a radiator in a magistrates court for five hours.

Premier is a joint venture between facilities management outfit, Serco, and security giant Wackenhut - whose private prisons in the US gained notoriety following a string of inmate murders and 'redirected funds'. Wackenhut (UK) Ltd also run several immigration detention centre contracts. Staffordshire police would not disclose details of the Premier contract, citing "commercial confidentiality", but in a statement, chief constable, John Gifford, says: "We welcome this partnership which will benefit both the force and the people of Staffordshire."

In opposition, Labour were against prison service privatisation. Now they are outstripping the Tory's plans for a privatised criminal justice system. Labour have doubled the number of private prisons since taking power.

If a police authority can aim to arrest more people to get their figures up, as suggested in Sussex, what are the implications for 'arresting on commission' when the situation goes commercial? "We have serious concerns about law enforcement for profit," a Police Federation spokesperson told SQUALL Investigations.

However, there no such concerns were expressed in the Queen Elizabeth conference hall in June. "There are sections of society that do not consent to the police but do, in a curious way, consent to the private security industry," opined Mike Welply, chief executive of the JSIC. One member of the public who probably wouldn't join the consensus is John Quaquah. Quahquah tried to sue the Home Office after being beaten by Group 4 security guards whilst detained at the Campsfield immigration detention centre near Oxford in 1997. After a long case the judge decided the government wasn't to blame for Quahquah's injuries as the jail was privately run. Quote gov/ACPO on accountability "It's a derogation of duty [by the government]," says Stephen Nathan. But it's a derogation this government seem all too willing to embrace.

"Imprisonment and the use of force against people are so fundamental to their basic liberty that they cannot be trusted to commercial organisations," says human rights lawyer Mike Schwartz. "A justice system should be directly accountable to the people not to company shareholders."

But maybe it is accountability that lies at the bottom of the policy. Those within government who have been following a dalek-style 'privatise, privatise, privatise' line believe the further government distances itself from the actions of its contractors, the less responsibility it needs to accept when things go wrong. Power is retained in procurement.

The same is true with law enforcement as it is with health or education provision, where private finance has slipped from infrastructure provision to frontline teaching and clinical services. Subsidies, tax breaks and enormous PFI pay-outs mean it may not save money or benefit the public, but as Tony Blair says: "Government should not hinder the logic of the market."

Eamonn Butler of the free-market-trumpeting Adam Smith Institute agrees all the way: "The police are hopeless because they are a nationalised industry which is increasingly centralised and drawing away from its customers. I believe the police can out-source a lot of things. One does simply need to have a lot more private security" From super-caretakers to wardens to custody service providers to the hand on your collar, the power creep of the private police is already well under way.

Related Articles

K-Ching! K-Ching! That's The Sound Of The Police!

- The privatisation of public security and policing begins as private security firms sign contracts - Feb 2001

Corporate Cops - Looking at the relationship between McDonalds and the British Police - 2000

Who's Policing The Police? - Investigation into the activities of the Police Complaints Authority - 2000