Book Reviews

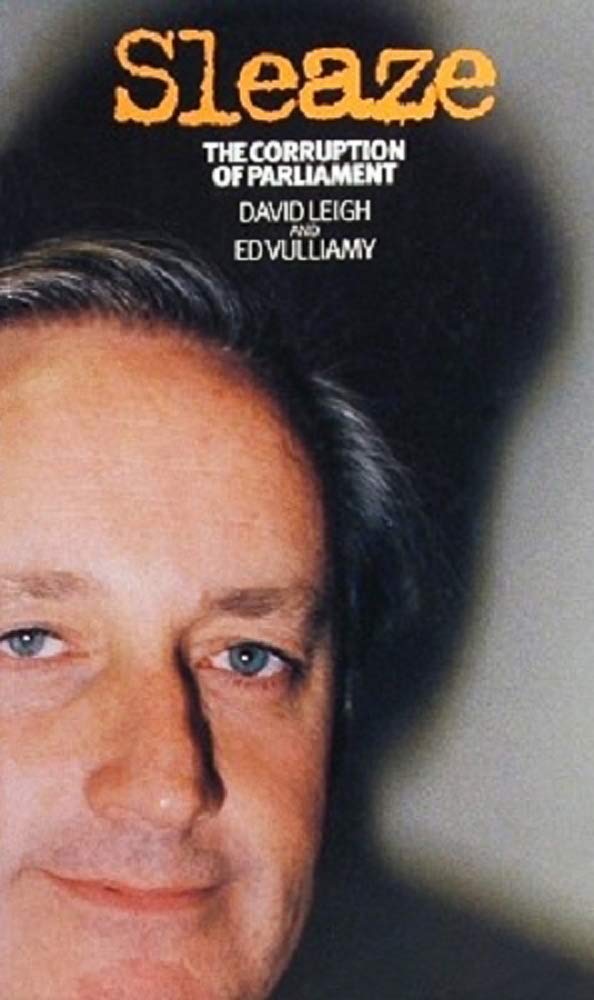

Sleaze: The Corruption of Parliament

David Leigh and Ed Vulliamy

Fourth Estate, 1997, £9.99 pb

Review by Sam Beale

Squall 15, Summer 1997, pg. 52.

It could have been the colour on the TV playing up again but Neil Hamilton, former Tory MP for Tatton, appeared to go a rather strange shade of green/grey when his successor, the refreshingly independent Martin Bell, was announced on election night. Not before time. Hamilton lost his seat for one reason alone: sleaze. This now familiar word was defined in 1995 by Lord Nolan, during his investigation into standards in public life, as ‘a pervasive atmosphere... in which sexual, financial and governmental misconduct were indifferently linked’.

Leigh and Vulliamy’s book specifically focusses on the cash for questions scandal. Once through the wave of powerlessness inspired by the knowledge that surely it has ever been thus (‘politicians are corrupt? You don’t say...’), this book reads like an adventure story in which truth and integrity are the heroes. The mind-blowingly brash and bent Hamilton gradually emerges as the quintessential slimeball villain as his acceptance of ‘brazen bungs’, holidays and expensive gifts in return for political compliance benefiting a repulsive list of corporate interests are revealed.

The truth about the lobbying business (of which Ian Greer Associates is currently the most well-known tip of a huge iceberg) is beyond disturbing. The most obscene of his professional relationships as recounted in Sleaze was with the Serbian regime, shortly before the world learned the extent of anti-Bosnian muslim atrocities.

This is, on one level, a depressing and laborious dissection of the worst elements of this country’s parliamentary processes. But it is given an edge by the direct involvement of the authors as journalists reporting the story as it unfolded, and the creative embellishment they have applied to descriptions of Hamilton's ill-gotten shopping trips and hotel stays.

The chapter entitled End Game recounts efforts by various newspapers and TV documentary teams to break the story. There is an excruciating section where a number of journalists are banging their heads against brick walls trying to get MPs to admit that cash changes hands for questions in the Commons. Finally, one reporter manages to get a positive disclosure and it seems as if, at last, there might be the big chase after which the baddies get blown away when... oops, the journo in question is travelling home on the tube when he realises the pause button on his dictaphone has accidentally switched on during the interview.

A meticulous description of The Guardian’s legal team, building its defence against Hamilton and Greer, is appropriate in light of the fact that the case that was never heard, and thus the facts of it have yet to be fully aired in public.

This book is important because it offers unique insights into the machinations of the ‘Mother of Parliaments’ pertinently described in the book as ‘a Looking Glass world which seemed perfectly normal to its inhabitants, but utterly impenetrable and strange to any outside...’ It reveals and describes the specific processes by which vested interests are to be found lunching together. It alerts us to connections and connivings beyond our worst imaginings and thus increases our future chances, not of preventing the corrupt being corrupt, but of hammering the bastards when they are.

Related Articles

Ex-Actors Of Parliament - Shed no tears - it’s yer Squall political graveyard, including Tory ex-MP Neil Hamilton amongst others - Squall 15, Summer 1997