International SQUALL

Organise, Invade, Produce! Brazil’s Rural Squatters

Brazil's rural poor are fighting back with increasing force. Simon Lewis tracks the country's most radical and important social movement. Photographs by Regina Vileda Gilmar.

Squall 14, Autumn 1996, pp. 60-61.

Five hours by train, one by tube, eleven by plane and two sleepless days and nights by bus. It’s getting dark, I’m tired and not entirely sure where I am or where I’m going. Certainly not the best time to arrive on the front line of the tense battle for Brazil’s rural backlands.

I am about to arrive at the increasingly famous ‘Acampamento Giacometi-Marodin’. This is the largest land occupation by the land rights group ‘Movemento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem-Terra’ (‘Movement for Rural Workers Without Land’). They want all Brazil’s unproductive farmlands to be appropriated and given, as small plots, to the rural poor. Their basic tactic is to invade and occupy large stretches of unproductive land. They then live there, refusing to leave until they each get the legal title to a small plot of land to live and grow food on. Or, of course, until the military police remove them.

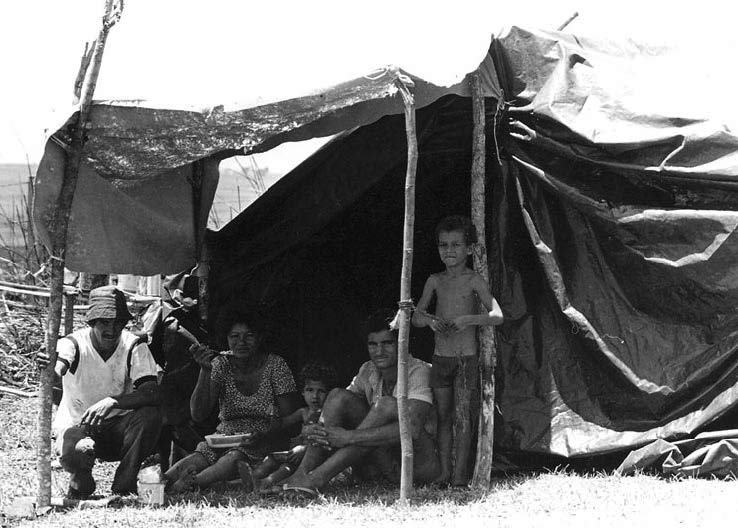

The bus rounds a bend, screeches to a halt. There before me, from the roadside, as far as I can see in the dim light, almost 12,000 people have made their ‘home’ here. Row upon row of small home-made, wooden-frame ‘houses’ draped with black plastic secured by vines or string. Getting off the bus and walking through this city of plastic is a shocking experience. But it’s not only extreme poverty that greets you at the camp gate. What is most striking, apart from its sheer size, is the order, cleanliness and even (dare I say) the tranquillity of it all.

Three thousand families living in absolute poverty in Brazil conjures distinct images. However, in the southern Brazilian state of Parana it’s very cold, it’s winter here and you can see your breath. Despite this, sandals and shorts abound. The land is a bizarre mix of monkey puzzle pine and palm trees. It doesn’t look especially tropical. There are no piles of rubbish, no stagnant pools of water, no rampant epidemics of disease. The ethnic mix is remarkably diverse. Surprisingly, the majority are of Eastern European descent, immigrants brought in when European and North American companies built the railroads here in the last century.

Talking to those who’ve chosen to live in this plastic city rapidly becomes repetitive. All say similar things. “A piece of land to live and farm on. Somewhere I can have a nice house and live with dignity and respect,” as Reni Perieras da Silva, 24, an agricultural worker put it.

Before moving to the camp at Giacometi, Reni did the only work available to him. Working in the fields he was paid ‘by the sack’ that he filled with, say, beans. He claims his monthly pay was below Brazil’s official minimum salary, currently US$100 per month which hardly pays for enough food. Prices here are broadly similar to those in Britain. Reni and the other 3,000 families at Giacometi want 15 hectares each and some credit from a bank to get started. The farm they’ve invaded covers an area of 83,000 hectares.

There are no sources of income for those living here and it’s not possible to plant crops as the farm owners are said to destroy them. Most assistance is of the self-help variety as Ernesto Fiera, 44, explains: “We have no jobs. No social assistance [security], only our families and our friends on the assentamentos.” An ‘assentamento’ is somewhere where they have already won land and are producing food. Some of this food is then given to needy occupiers. Otherwise many get money from their families to get by on a monotonous diet of rice, beans and bread.

The considerable organisation needed to operate the camp efficiently is achieved by an impressive system of direct participatory democracy. Each family belongs to a group with around 30 other families. All group problems are addressed by regular meetings. In addition they each nominate coordinators for various posts such as health and security. The co-ordinators from each of the 92 groups of families meet regularly to discuss camp problems.

Generally life seemed relaxed though there are some strictly enforced rules. Those who spend their time drunk are told to leave, as are drug users and prostitutes. All children are expected to attend the school, which is largely run by activists. One of the camp’s goals is that everyone should learn to read and write. School, as with most other aspects of camp life and culture, is very DIY. Jose Deviar Ramos, 19, is one of the teachers. “I’m here because I want a plot of land, but I did well at school so I volunteered to be a teacher”. But even with Jose’s and the children’s enthusiasm, they face an uphill struggle as things like books and notebooks are a rarity.

On the health front, it’s also DIY. There are no doctors, just an ‘ambulance’ provided by the local council. They have a pharmacy of sorts stocked with a very limited array of ‘western’ medicines and piles of leaves and roots for herbal remedies. It is staffed by landless volunteers living in the camp. Yet despite all these safeguards twelve children have died of a mix of cold, hunger and disease in the four months the occupation has been running.

This type of land squat is standard practice for Movimento Sem-terra (MST), who since 1984, have been co-ordinating and organising land occupations and helping those who have won land to produce food. The size of that movement is somewhat staggering. This is not a few idealists doing a bit of direct action. Figures from the religious monitoring group Comissao Pastoral da Terra show that in 1995 there were 30,500 families engaged in illegal invasions to get land, spread over almost 150 sites throughout Brazil - a 100 per cent increase on 1991. But with no membership or lists of names verified, numbers are hard to come by.

The economist, Joan Pedro Stedile - one of MST’s most respected leaders, claims 150,000 families are already settled or illegally occupying land with 5,000 described as militant. Impressive though these figures are, they should be set against the recurring estimate of around 12 million people in Brazil being ‘sem terra’. The problem is enormous, with millions migrating from rural areas to cities or the Amazon forests where they live in the infamous favelas in worse conditions than even the camps.

Recently public support for MST within Brazil has verged on the unbelievable. In an opinion poll in May to obtain ‘approval ratings’ of various ‘public institutions’ for Brazil’s national newspapers, MST came fifth with 59 per cent approval. Interestingly, only the press, Catholic church, armed forces and public universities got high ratings. National congress (parliament) polled 27 per cent.

The rich and the powerful aren’t, of course, standing back and letting those ‘vagabonds’, as they call them, get their own way. Activists have been intimidated, imprisoned, tortured and murdered. Last year 41 activists were killed in land conflicts with 381,000 people involved in over 500 conflicts according to the monitoring group Comissao Pastoral da Terra. This is in addition to the some 63,000 families on the receiving end of violence against their possessions and property.

It is very difficult to assess if the violence is escalating but one thing is certain - the worst postdictatorship violence committed against MST activists happened this year. On May 17th, 4.30pm, Brazil’s military police charged at a group of about 1,200 MST activists who were protesting by blockading a highway in the Amazonian state of Para. Though virtually unreported in the Western media, the resulting melee left 19 ‘sem-terra’ dead. Close examination revealed that summary execution via a bullet in the head had been the most common cause of death. As the operations commander, Coronel Mario Collares Pantoja said on the day: “Mission complete. Nobody saw anything. ”

Fortunately he was wrong. The amateur video footage was some of the most horrific seen on TV. Brazilians were genuinely shocked.

Several days later, events took an even nastier twist. It was revealed to the press, anonymously, that the big landowners (fazendieros) had paid the police the equivalent of some £60,000 to carry out the operation. The executions were designed to remove further protests and occupations in that area. The plans seemed to have backfired somewhat with MST redoubling their efforts to secure wholesale land reform.

Despite these appalling murders, the violence is sporadic and fairly confined to certain localities. At ‘Acampamento Giacometi’ there are no problems with violence. There are just too many people and they are too well organised. The police and landowners rarely pass by. Talking with these people there is a real sense of hope. A hope that maybe soon they won’t have to live so hand to mouth: “A piece of land to live and farm on. Somewhere I can have a nice house and live with dignity and respect.”

Related Articles

Zapatista! - Update from the jungles of Chiapas - Squall 14, Autumn 1996