Paint The Town

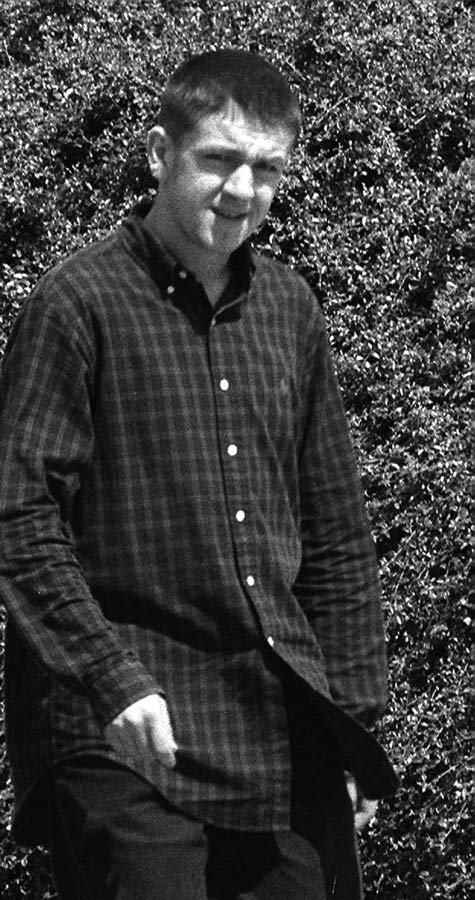

Simon Sunderland was arrested just prior to starting an art school course. His crime? Painting colourful graffiti tags four years earlier. His punishment? A five year prison sentence. Sally Chesworth interviews an artist behind bars.

Squall 14, Autumn 1996, pp. 18-19.

It cost £7,000 to remove the efforts of a teenage graffiti artist from the sites of urban decay he was trying to enliven. It now costs £22,969 to keep him in one of Her Majesty’s hotels, where he’s serving five years for practising his craft, known to the authorities as criminal damage. In these times when the country’s jails are creaking with overcrowding, there are many people whose accounts of their incarceration leave you rolling your eyes in disbelief. But this young man’s story has to be among the most bemusing.

Simon Sunderland, now 23, was sentenced in March for painting graffiti around Sheffield in the early 1990s. His tag,/signature - ‘FISTO’ or ‘FISTA’ - identified it as his. Much of his work decorated abandoned buildings or remote places like a sewerage plant and a bridge on the M1, hardly describable as examples of civic pride.

For Simon, the ludicrousness of his situation only heightens his pangs of injustice. He was never caught in the act of painting - the police came for him early one morning. Before his arrest he was expected to start a college art course with thoughts of doing a degree. He’d been developing his drawing skills and presented his portfolio at court but says the judge didn’t look at it. The Probation Service recommended that Simon be given a non-custodial sentence because it would not serve the public interest for him to be locked up any longer than the five and a half months he had spent on remand. In meting out a five year sentence, the judge said the term was a deterrent , which Simon finds hard to reconcile with having been out of trouble for three and a half years. He and his supporters see it as an aberrant decision which they hope will be overruled next month.

“If there is to be any aesthetic doing and seeing, one physiological condition is indispensable: frenzy. Frenzy must first have enhanced the excitability of the whole machine, else there is no art. ” - Neitzsche

“You ask yourself: where is the vandalism, in the graffiti art or in the concrete that serves as its background?” - German museum director

These are extracts from some of the reading matter that has inspired and encouraged Simon during his months inside. Below, Simon describes the motivations behind his graffiti, what this and his current work means to him, and his reactions to being criminalised for his art.

“Graffiti art is to me a pure form of art - no money, no rules in the style and content, it’s visible and it still seems vibrant, and the fact that it is a self-taught medium and has no written history, so no borders or rules can be made or heeded to.

“The graffiti I did wasn’t done to offend nor harm anyone. I had no financial motivations, on the contrary, I wanted to share it with people, or at least those that liked it. My motives were sincere. I believe I owe a great deal to my graffiti art past. I work in a working class area, it’s not really a positive place for someone interested in art or anything else for that matter. Neither was art at school which I found boring. Graffiti seemed exciting, no one telling you what to do. It was rightly or wrongly a way of getting some kind of recognition. It was also the sheer love of trying to do something positive in an atmosphere and area of the complete opposite. I’ve now progressed, matured, and although I don’t do graffiti, I will never stop doing art - it’s part of me, something I love, something I’ve created, developed and learned myself. It’s taught me many things about life in general and not just art. I was trying to further myself more than I’ve done already, though somebody decided they would try to ruin my life. A year or two ago, a London graffiti artist was given 18 months probation for a lot more damage on tubes and walls.

“For all its bad sides, graffiti has more balls than half of this art in galleries. Imagine you’re scared, freezing. It’s two in the morning. You’ve a few colours so you don’t have too much paint to carry and when you get to the place you’re going to paint there is a barbed wire fence and four live electric rails, and then you’ve to paint in virtual darkness, shitting yourself to create something creative.

“For many kids in northern working class areas, art isn’t encouraged. Art is seen as the ‘property’ of the middle and upper classes. Northern working class kids are meant to work in industry, as in my area where steel and mining were the main sources of employment. Now that these industries are in decline or extinct, the newer industries of unemployment, drugs, booze and crime have taken over. To me these options aren’t very inspiring. So with all the grief that graffiti has caused me, it was this that gave me the impetus to develop my art in other directions.

“Graffiti isn’t conventional, but I think it is sad when it is dismissed and misunderstood. So many kids, once they’ve finished doing graffiti, tend never to do art again. I believe that if they were encouaged, if local authorities took a more positive approach, they could help kids develop their skills and both could benefit from it.

“I know that in the society I live in, on the whole, graffiti is viewed as illegal, so I knew somebody wanted blood. I was expecting a punishment of some sort. But nothing like the sentence I was given. I feel that I was harshly treated because even the prosecution barrister had argued for a maximum sentence of between 12 and 18 months.

“I thought the sentence was unreal - logic I feel had little if any part to play when my sentence was passed. I’ve coped with prison I guess. Maybe I can answer this better when I’m out and am able to look back at it. I guess I’ve learned from it, not ‘cos of my “crimes” but the whole experience and I see what a pathetic system it is. The screws have been relatively OK. Most who’ve mentioned it can’t believe my sentence but there’s always the odd sad bastard who I feel doesn’t like the publicity my campaign and case have received. But they’re their own problem. Maybe it would be different if I was at a Cat A or Cat B (more secure) prison. But prison isn’t a holiday camp where you get a roof over your head and three meals a day, that’s a load of bollocks. Spending your time in such a small area with so many people, many who aren’t the friendliest of people, 24 hours a day, every day, isn’t my idea of a holiday.

“As for my chances in the art world. Well, it would be good for that to happen, but if it’s not so then that’s that. I’m not going to get stressed whichever way. I find it funny, if not strange that I can make cash out of something I love doing for a larf! It would be a bonus, but I’d never get taken in by it. I mean the enjoyment/expression is most important to me, if you don’t get/achieve that you’re more or less fucked! Getting a nice little ego and a knack for disappearing up your rectum seems boring and sad, and fame and money (too much) don’t seem so over important.”

The backbone of his growing campaign is his Mum, Angela, and her two sisters who have tirelessly pushed for his release. Appalled by the stance taken by the city council they feel Simon has been used as a scapegoat for all manner of social ills.

“There’s been a climate of suggestion that Simon cost Sheffield vast amounts of money,” says Angela. “The council has claimed that graffiti was responsible for businesses refusing to invest in Sheffield and for the poor health of some of its residents. The media has attempted to pin the blame for all this onto Simon. To blame Sheffield’s social and economic problems on artwork that’s colourful and exciting is ridiculous. What is ignored by all the publicity is the effect on Simon’s life now, his future and his hopes for the rest of his life. Imprisonment and the massive costs of keeping him there are doing no good for him or for society. Simon’s art did no one any harm and it brightened up some grim spots. Is that worth sending him to prison for longer than most rapists?”

Simon Sunderland’s appeal was heard in the High Court on October 3rd. The judges decided that a five year sentence was “out of kilter” with his conviction. They ruled that two years was a more appropriate sentence. Having served a year already he was released the following week.

Related Articles

Metaphysical Graffiti - An art activist from Bristol has been causing a right ol' stir with his brazen approach to conscious graffiti - 2000