International SQUALL

World Bank Evictions

Squall 9, Jan/Feb 1995, pg. 36.

"One pound in every seven of Britain’s contribution to the Bank is spent on projects involving the forcible resettlement of people." - (1994 World Bank Briefing)

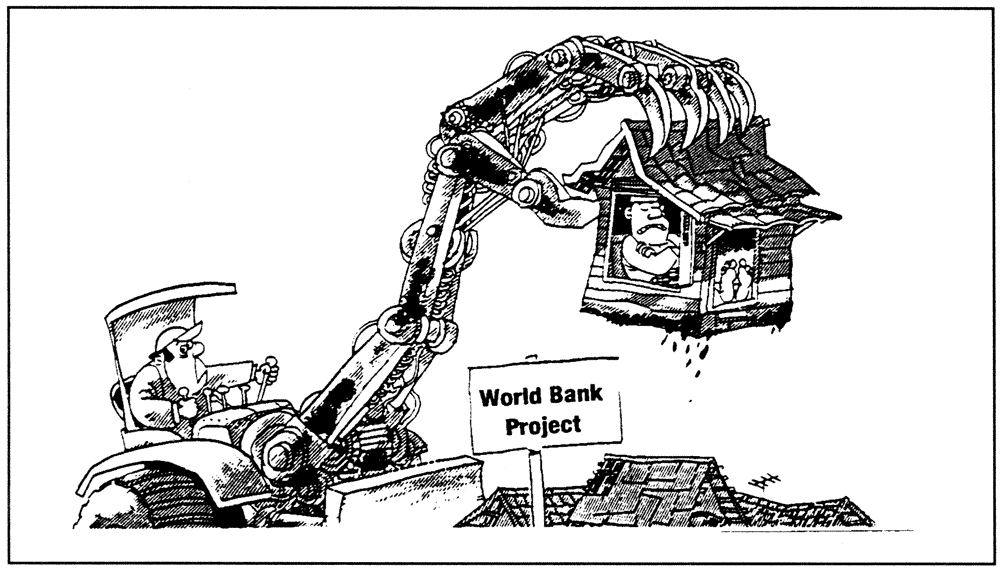

Current World Bank (WB) projects throughout the world are leading to the dispossession and involuntary resettlement of up to two million people.

Since 1948 as many as 10 million people have been forced off their land for dam projects alone. A 1994 World Bank review admits that WB projects, intended to alleviate poverty, invariably exacerbate it. It is clear that the main beneficiaries of these projects are the multi and transnational companies who receive lucrative construction contracts.

An Ecologist briefing on the Bank’s activities says that the WB has acknowledged that “projects involving resettlement have increased landlessness, increased joblessness, increased homelessness, increased marginalisation and increased food insecurity”.

The Bank’s own resettlement policy clearly states that, following eviction, people should be relocated and their living standards matched or improved upon. This simply does not happen. In addition, before projects are approved, the numbers of people likely to be evicted are grossly underestimated. The Ecologist briefing notes that “an urban development sector loan to Pakistan was recently approved by the Bank on the assumption that only 500-600 people would have to be resettled: a subsequent field trip by Bank staff found that the true figure was likely to be in excess of 20,000”. The WB has been unable to give a single example of a project where resettled people have been rehabilitated.

In the case of the controversial Sardar Sarovar dam project in the Narmada valley, India, the Bank completely omitted to take into account 200,000 people affected by the dam and its related canal systems. The dam’s opponents are clear that the costs of the dam have been grossly underestimated and its benefits to the region exaggerated. Medha Patkar, India’s leading and seemingly fearless environmental activist and Narmada Bachao Andolan (Save Narmada Movement) have been fighting to prevent the removal of thousands of families from the Narmada river valleys to barren “relocation camps”. Protesters have repeatedly been banned from entering the area to support villagers. Many have been arrested and beaten.

In the summer of 1994 a ban was placed on music, dancing, “gesticulating” and “slogan shouting” against the project. Medha Patkar went on hunger strike for 26 days in November/ December, demanding a government guarantee that work on the dam would stop.

Construction has now been delayed and the Indian Supreme Court has condemned the government’s failure to answer key questions about the dam, and has asked for a new plan including rehabilitation of displaced families, a reassessment of the height of the dam and environmental protection.

Again in India, in Singrauli, the WB is giving money to projects in an area already home to the Rihand dam, 12 open cast mines and five coal-fired power stations. In this area more than 300,000 people have been displaced to make way for the projects in 25 years, some families have been evicted without compensation four or five times. Despite this, in 1993, a further $400 million loan was approved to expand coal-fired power stations including those at Singrauli. Virtually no cash has been made available for resettlement.

There have been calls for changes in the WB’s policy and for penalties and incentives to be introduced to help ensure resettlement programmes are well-planned, funded and followed through by the Bank’s staff. Despite recent claims that they are abandoning their mega-project obsession, WB management tends to ignore the flouting of loan conditions, including resettlement provisions. Its current plans to simplify its staff directives, reducing mandatory procedures, suggest no positive changes on the horizon.

Related Articles

Tribal People Dammed - The occupants of the Narmada Valley in Northern India have been evicted to make way for a mega-dam. Sam Beale reports - Squall 11, Autumn 1995

Heard World - Gibby Zobel and friends attended the Peoples Global Action conference in Geneva and talked to a host of worldwide activists - Squall 16, Summer 1998

Prague A Go Go Boom - The IMF and World Bank will hold its 55th annual summit in Prague. Thousands of anti-capitalist protestors will be there too - August 2000