You've Been QUANGO'D

There are now more people working for quangos than there are in local government. Freelance housing journalist, Patrick Nother, takes a look at the disappearing accountability, as exampled by the rise of the faceless housing quango.

Squall 8, Autumn 1994, pp. 28-29.

Once upon a time, in the 50s and 60s, nearly every BBC news broadcast seemed to end with the plummy, dinner jacketed newscaster reading announcements from the Government or Opposition about council dwellings completed or new numbers promised. Both Labour and the Conservatives loudly boasted their commitment to an ever-expanding programme of new build, as slums were cleared and system-built estates went up in their place.

Much of the development has long since been regretted, as 'streets in the sky' turned out to be so much 'pie in the sky' and faith in steel and concrete crumbled. But the level of output was phenomenal, with the municipal housing boom peaking in 1967 when over 200,000 homes were built. By 1979 the local councils of Great Britain owned a grand total of more than 6.5 million homes.

But no longer. Since the early '80s almost a quarter of the stock has been lost through 'right to buy' and large scale transfers to housing associations (HAs) and housing action trusts, while development of new social housing has become the almost exclusive preserve of HAs. Last year local authorities built only 1,200 homes.

No one can claim that the Government has anything that even resembles a coherent housing policy, but it does have a number of dogmas and treasury-led constraints which will continue to transform the provision of social housing.

One initiative is the promotion of HAs as managing agents of the 864,000 mostly privately owned empty properties around the country (the HAMA Initiative), while new developments are cut back. Private landlords and letting agents are getting in on the act, but things are moving very slowly and are of little comfort to the tens of thousands of squatters threatened with imminent eviction by the Criminal Justice Bill.

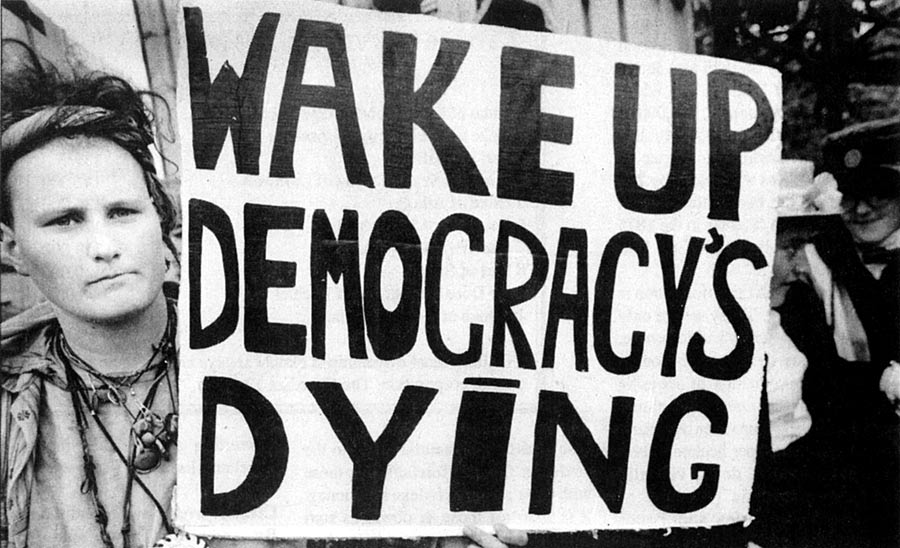

But the big political issue of the last few years has been that of the overall quangoisation of new housing provision through HAs as well as their funder and regulator, the Housing Corporation (HC). But be forewarned, in the future this may appear relatively benign.

Quangos (quasi autonomous non-governmental organisations) are bodies which do the work of government without being democratically elected or accountable. A recent report by Charter 88 (Ego Trip - Extra Governmental Organisations in the UK and their Accountability) identified more than 5,500 executive bodies from all walks of public life lacking the "scrutiny, openess and accountability which are essential in a democracy".

With about 70,000 appointees on their boards (these individuals have become known as "the New Magistracy"), in 1992/93 they spent almost a third of all public expenditure. More, that is, than all of local government.

The second largest individual quango is the Housing Corporation, with a budget of nearly £2.4 billion in that year (though now beginning to fall). The Corporation's committee and chief executive are government appointments and while it claims a consultative role with its real boss, the minister of housing, for all intents and purposes it just carries out his policy.

Charter 88's quango count includes more than 2,000 HAs, although associations are voluntary or charitable bodies. But they operate "at the local level under appointed or self-appointing committees", which is how Charter 88 defines the New Magistracy. And they also spend the HC's money for it. In line with Citizen Major's replacement of democratic rights with consumer rights, HAs' "customers" have a Tenants Charter and an Ombudsman.

Before it became the Government's chosen vehicle (or "poodle", as some have called it) for providing new social housing, the voluntary housing movement complemented council housing, meeting a broad range of specialist needs. Over the last half decade, however, the movement has expanded rapidly and now manages about a million dwellings.

This has created a serious identity crisis, and the movement's self-doubts and internal contradictions are currently being addressed by a Governance Inquiry, set up by the National Federation of Housing Associations (NFHA). This is looking at such questions as should the present voluntary committee members be paid, and what exactly should be the relationship of the committee to the chief executive and senior officers?

Just about anything could result from the Inquiry, but one very possible scenario has the introduction of optional payments to directors so inculcating the culture of commercialism into the 90-odd "premier league" associations who now own 65% of total association stock, that in no time they break away from the movement and turn themselves into private limited companies (plcs). Such pressure already bears on them.

Since the 1988 Housing Act introduced a regime of mixed funding for HAs, with increasingly smaller grant (HAG) rates requiring closer and closer relationships with private lenders, successful associations have become very familiar with the ways of The City.

The recently announced Housing Association Grant (HAG) rate for 1995/96 of 58% (down from 62% this year) will mean even fiercer competition for private loans, and pic status could provide an association with opportunities for creatively utilising the equity locked in its properties, ensuring future private funding at even lower HAG rates.

The Government is already considering offering HAG to private developers in competition with HAs.

Or it might just go the whole hog and curtail bricks and mortar subsidy altogether, allowing social rents to rise to a market level with problems of affordability being addressed through the personal subsidy of housing benefit payments. But then there are also plans to cut housing benefit! Either or both moves would further marginalise workers already condemned to low incomes in Mr Major's much trumpeted "low wage economy".

Government policy has quangoed social housing, with housing quangos effectively removing new housing provision out of the control of democratically accountable local councils. It now seems quite capable, in one way or another, of privatising it all.