International Squatters

Squall 6, Spring 1994, pp. 16-18.

In an international context, squatters are something of a social indicator species.

In the Third World, illegally squatted settlements outside cities indicate the impossible prices of land and rent for the poor and the displacement of huge numbers of dispossessed peoples from rural areas. In Western cities, squatters generally suggest abysmal housing and social policies and a palpable inability of the market to deal with basic needs.

During times of recession businesses collapse, residential property lies vacant waiting for economic upturn and public sector housing falls into disrepair through lack of funds. The unacceptability of this situation is highlighted as large numbers of homeless people inevitably turn to squatting.

It is important to point out that in some European countries squatting is not perceived as a housing issue. Of course that is not to say there are no housing problems in these countries but the squatting laws are such that squatting is not a viable option in terms of meeting the immediate housing needs of the homeless. The act of squatting is about making a political or cultural statement: people taking control of their communities, artists taking control of their arts, services meeting needs. The Criming Justice Bill, if passed, may make squatting in Britain more like that in Europe, more a political statement and less a safety net to homelessness.

In these places squatted buildings become cultural centres. They are about community involvement in the arts and provide workshops and meeting places, information, entertainment and support. They gain approval within communities and from the media and this makes heavy-handed evictions politically unwise. Some of them even make agreements and are legitimised (for as long as the land they occupy remains worthless).

Here is a smattering of stories of Squalls around the world; what squatters in other countries are up against and their ingenuity despite it.

Switzerland

As in Britain squatting is unlawful in Switzerland, the difference being that almost all housing is privately owned and these owners do not need court cases to secure evictions. Despite this, in Geneva (the most squatted city in Switzerland), there are around 50 squats and 6 large centres with venues, cafes, bars etc. In such a small city the squatting community is close-knit and squats are easily identified as most are covered with artwork and banners.

In Bern the Reitschule is a large squatted building which has become a major arts venue for the city. It was originally squatted in 1980 but was closed by police after a year. It was re-squatted as an autonomous centre in 1987. There are now venues, cinemas, theatres, a printing workshops, an information centre, a cafe, a women's group, and a gay/lesbian action group.

The Reitschule has community and media support because of its role as a cultural centre. Members of the Reitschule also keep the place in the news by organising frequent demonstrations. The squat has secured an agreement with the city and has been virtually legitimised.

No-one actually lives on site but around three hundred people are involved in running the centre. They regularly provide free food for heroin addicts and run a rigorous anti-heroin campaign. This contributes to their media support as Switzerland has a major heroin addiction problem.

Germany

Squatting in Germany is illegal. The police can effectively evict squatters whenever they want to under the law of Hausfriedensbruch: breaking the peace of a building or an area of land (the time-scale of evictions varies with local governments). After being arrested under this law, German squatters are often charged with other crimes such as criminal damage, burglary and conspiracy. The authorities tend to see squatting as a direct attack on state institutions and squatters in Germany are usually making apolitical statement. The German squatting movement has always been associated with radical politics.

Throughout the 70s and early 80s West German squats were loud and proud. Banners hung outside announced that the building was ‘besetzt’ - squatted. These squats always involved large numbers of politically motivated people, it seems very unusual for two or three people to quietly squat a place for a few months. To maintain control of a building it has always been essential to have an organised campaign that raises the political stakes so high that the authorities hold their fire.

Since re-unification German squatting has changed. In East Berlin there are more derelict and empty properties, so the squatting scene is more like London’s; the emphasis being on finding a home. After the Wall came down big, traditionally radical and squatted areas in the West of the city such as Kreuzberg (where whole neighbourhoods were squatted) found themselves in the centre of the new city. This is the part of Berlin the authorities most want to spruce up. So many of West Berlin’s radical squatters have now moved East to areas like Prenzlauer Berge which, following reunification, is pretty far down the redevelopment list.

Denmark

The highly successful Free Town of Christiania, an ex-military base in Copenhagen, was squatted in 1971. The town was based on collectivism and autonomy from the system, its motto: Action Gives Change.

About 800 people currently live in Christiania. Over the past year or so there have been regular police raids on homes in the town, supposedly in search of hashish. It seems that the authorities are intent on turning Christiania into a “normalised” recreation area for tourists and the population of Copenhagen. Residents of Christiania see this as a threat to 22 years of “self-administration”, as it obviously is.

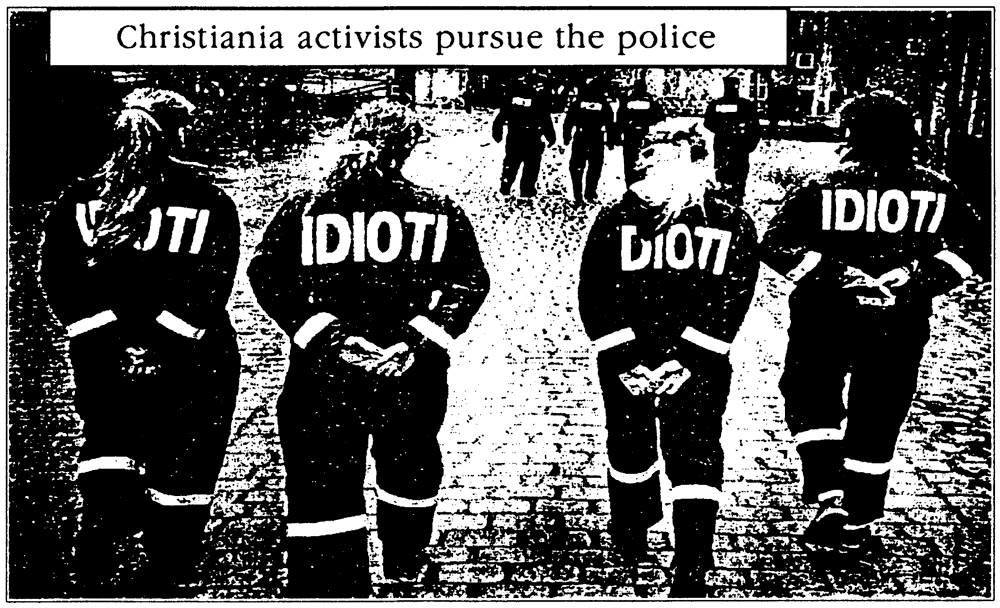

One recent action against police harassment involved Christiania activists dressing in identical outfits to those of the police except they had IDIOT! (IDIOCY) rather than POLITI (POLICE) written on their backs.

USA

American law states that “if you have maintained residence for thirty days or more you cannot be evicted without a court hearing except by a marshal with a warrant for eviction”.

On August 17,1993 there was a mass eviction of one of the oldest squatter camps in Manhattan known as “The Hill” or “Teepee Village”. Community activists were appalled as bulldozers moved in to demolish the site before all the residents had moved out. The mayor’s office gave the reasons they apparently always use for evictions; the camp was ‘unsafe’ and there was ‘drug abuse’.

Glass House, home to around 40 squatters on the Lower East Side of New York, is targeted as a housing project for Aids/HIV sufferers. This project has the support of much hated NYC Councilman Antonio Pagan who has opposed every other Aids housing facility in the area.

His support for this one seems directly related to the facts that it will displace squatters, is not on valuable real estate and that a large amount of money (which he will not have to account for) has been made available for the project.

An alternative plan, put forward by Housing Works, an experienced group of Aids workers with a good track record, is opposed by Pagan. Housing Work’s project is on valuable real estate and is a legitimate Aids project ie, it will not make money. In addition, it will offer medication and clean needles for heroin addicts. Pagan opposes the plan because he claims the site is a ‘drug free zone’ (the project he backs will refuse to treat drug users). He is actually rallying support with this information, without mentioning the ‘rampant heroin addiction on the same block’ (The Shadow, No. 30). The dispute has created a furore in the city over the last six months.

A public meeting held by a local community board (members include several of Pagan’s mates and some local property owners) ended with police beating and arresting squatters at the command of the meeting’s Chair. Despite protests, a petition of support for Glass House from locals and widespread approval for the Housing Works proposal the board granted ‘site control’ of Glass House to a member of the board who is also one of Pagan’s cohorts.

The meeting was disrupted, unsurprisingly, by squatters who had been told at a previous meeting of the Human Services Committee “you’re not people, you’re just bodies”. At this meeting no squatter was allowed to speak uninterrupted for more than 25 seconds. Demonstrations and protests continue.

Slovenia

London, Berlin, New York, Ljubjana... Ljubjana, capital of Slovenia, which gained independence from the former Yugoslav Federation in 1991. Before independence the Slovenian government promised Metel Kova, a huge ex-communist army base, to the people as a centre for the arts. In the event the government reneged, so the people squatted it anyway. Well, they moved in, there is not actually a word for squatting in Slovenian.

Metel Kova has achieved cult status in Slovenia as a symbol for freedom and change. 145 art groups from all over the country are now based there. There are art galleries, a theatre, venues and a cafe. The Punk House is where the military garages were; the Hell’s Angels bar is in the old canteens and a Youth Hostel has replaced the prison. There is a creche, an aids information centre, a gay and lesbian centre, facilities for drug addicts and the disabled.

A TV company visits every week to make a 30 minute programme and student radio stations regularly record their programmes at the base. The squatters have the support of the media, the community, the unions and, it appears, even of the ex-military commander of Metel Kova who has, bizarrely enough, provided the squatters with mobile telephones. The government has control of the barracks, which were not squatted, and pays one security guard to watch the base..

A few weeks after the squatters moved in the water was turned off. The silent demonstration which followed involved members of Metel Kova taking their toothbrushes to a fountain in the city, cleaning their teeth in it and then forming an orderly queue to use the toilets at the town hall. Finally, the squatter-friendly ex-military commander came up trumps again and paid for the fire brigade to take them a huge tank of water.

Holland

Like Berlin, Amsterdam has a long tradition of radical squatting. Currently over 50 squatters in the centre of Amsterdam face eviction from 20 buildings in two streets under laws similar to present English legislation. ABN-Amro Bank intend to re-develop on the squatted sites including de Kolk, de Dirk and de Garten.

The buildings up for demolition were part of a busy community until the mid-70s when speculators moved into the area and started buying up property, pushing up the rents and chasing out residents and shop owners. They remained empty and fell into disrepair until 1991 when squatters moved in and started working on them. In 1992 they opened a non-profit-making information centre and cafe in one of the buildings and de Dirk was opened as a music venue. They also run a food co-op, a bar and a bicycle hire shop. All these initiatives are under threat.

Another action recently undertaken involved 70 Yugoslavian refugees who arrived in the city with no home to go to. Members of the squatting community opened up some empty property and housed the lot.

In June 1992 ABN-Amro announced plans for the re-development of the whole area. Their application was refused because the development would destroy too many ‘monuments’. In September 1993 they entered revised plans, the only difference being a promise to renovate the monuments. ABN-Amro already have quite a collection of monuments from past developments which they have done nothing to preserve. Nevertheless the plan was approved. The bank intends to build offices (10% of office space in Amsterdam is empty), shops and a car park for 400 cars. The entire development will cost around 200 million Dutch Gilders (about £70 million). Another developer intends to build luxury apartments on the rest of the site. As one of the squatters awaiting eviction said: “It is the people who deliberately leave buildings empty, letting them rot and eventually pulling them down who are the real criminals.”